Why We Should Care About Horseshoe Crabs

Behind my grandmother’s house in Massachusetts, a series of submerged cages float in the murky water of the brackish marsh. “He keeps horseshoe crabs out there,” she tells me of the man pulling up in a small skiff, “for their blood.” It can be sold for a serious profit to pharmaceutical companies seeing as for the past five decades or so, the ancient arthropods have played a pivotal role in the development of modern medicine.

As kids, my sister and I spent many summer days collecting treasures on the beaches of Chatham, the small Cape Cod beach town where my grandmother still lives. My favorites were the delicate and translucent exoskeletons shed by growing horseshoe crabs.

This past June, I spent a few days exploring those same beaches, where dunes rise up from the shore, topped with tufts of green beach grass that sway in the soft wind. The air there is salty and smells earthy, like soggy sediment and decaying reeds. While wading in the warm shallows of Harding’s Beach, I watched an Atlantic horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) inch out of the depths, its spear-like tail leaving a delicate trail in the sand. Seemingly unbothered by my presence, he made his way toward a pile of male horseshoe crabs vying for their chance to mate with the sole female on the beach.

As a child, spotting live, full-grown horseshoe crabs was relatively rare. In the 1990s, high harvest levels led to a drastic decline in populations up and down the mid-Atlantic coast of the U.S. With stricter management introduced around 2005, their populations began to rebound, a good sign for fans of these prehistoric marvels like me. However, our reliance on the unique biomedical properties of their blood is beginning to cause a new pattern of decline in an animal that has existed on earth since long before dinosaurs.

About the horseshoe crab

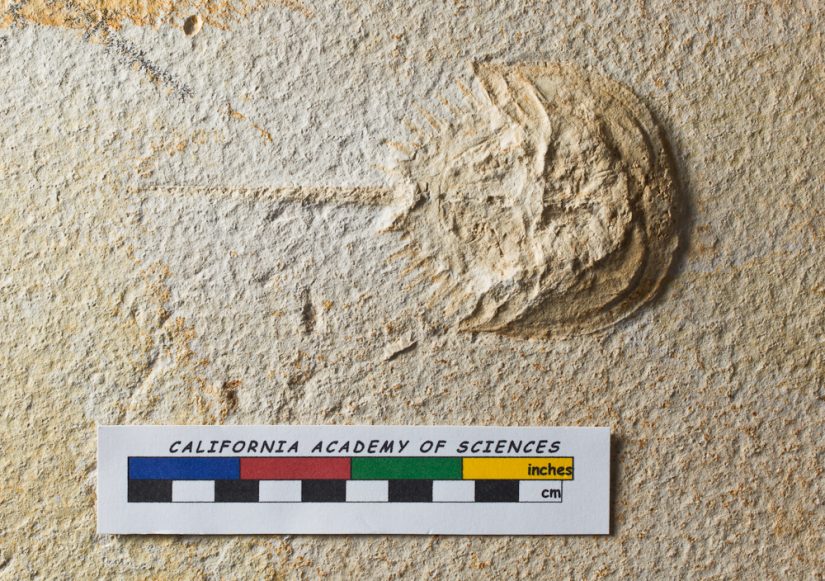

Technically, horseshoe crabs are not crabs at all. More closely related to spiders, scorpions, and the extinct trilobite, they fall within their own class of the Arthropod phylum called Merostomata, meaning “legs attached to the mouth.” With fossil records dating back over 400 million years, they are a relic of an ancient world living amongst us today.

Often called “living fossils,” the ancestors of the horseshoe crab survived multiple mass extinction events. Four extant species are found in today’s oceans on the eastern coasts of the United States and Asian countries such as Japan, China, and India. With little drastic change in their morphology, they still resemble their fossilized relatives.

Ecologically speaking, they occupy an important niche within coastal and estuarine habitats. Horseshoe crabs feed on small benthic fauna. The adults themselves are also food for a variety of animals such as sea turtles, sharks, and alligators. Their energy-rich eggs are a critical food source for seabirds such as the endangered Red Knot, which rely upon horseshoe crab eggs to fuel their annual 9,000 mile migrations.

Horseshoe crabs and humans

While horseshoe crabs are commercially harvested for bait as well as consumption, the primary anthropogenic threat to their survival is a direct result of the strong antibacterial properties of their strikingly bright blue blood.

In the 1950s, researchers discovered that Limulus polyphemus blood is very sensitive to the presence of endotoxin, a component of harmful bacteria that causes dangerous infections such as meningitis and pneumonia. Using proteins extracted from Atlantic horseshoe crab immune cells, scientists developed the limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) test, now a crucial component of ensuring the sterility of a suite of materials used in medicine. By 1977, the Federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of LAL, revolutionizing the safety standard for everything from vaccines and injectable drugs to the materials used in artificial joints.

It is hard to overstate the importance of horseshoe crabs to modern medicine. However, our reliance on them is beginning to have deleterious effects on their populations. Although the industry employs a catch and release strategy, there is little consensus on how many horseshoe crabs die as a result of “donating” their blood. Recent studies have shown that mortality rates may be as high as 30 percent, and that horseshoe crab spawning and mobility are impacted post bleeding. Regardless, the rush to develop billions of COVID-19 vaccinations has thrown the issue of using horseshoe crab blood into the spotlight, with many conservationists arguing its continued use directly threatens the survival of the endearingly odd helmet-clad creatures and the other animals that rely on them for food.

There may be some good news for the horseshoe crabs and sea birds, however. The use of a synthetic alternative to LAL called Recombinant Factor C, or rFC is slowly catching on. rFC has yet to be widely adopted worldwide, as it still needs to undergo rigorous testing, but advocates for turning away from the use of LAL for the sake of horseshoe crabs are optimistic about its future adoption. Especially with this new alternative, it would be a shame to stand by as a creature that has survived hundreds of millions of years slowly disappears.