Why is SMEA still so white?

Whenever I enter a classroom for the first time, I always end up lingering in the doorway for just a moment, surveying the room. Not for very long—just enough to flit my eyes across the faces of those already inside and assess whether I will be alone.

One of the first defense mechanisms I learned growing up as a person of color was to take stock of how many other people of color were in any room I entered. Although I was spared from the harsh forms of discrimination faced by other minority groups, particularly Black, Brown, and Indigenous folk, I experienced enough micro (and macro) aggressions to learn the importance of taking a cursory look for visible diversity in spaces I was going to be spending time. When I saw several other BIPOC folks in the room, I felt a slight sense of assurance, knowing that a space with natural diversity might be much more likely to be accommodating. When I saw only one other BIPOC in the room, I knew who might need allyship or might be an ally for me, even if the allyship only amounted to exchanging a knowing glance if someone said something problematic. And when I was the only BIPOC in the room, then I knew to be on my guard, ready to choose between code-switching, confrontation, or sinking into the background.

Sadly, I am often forced to employ this last tactic in marine science spaces amidst the overbearing whiteness of the field. It is a shortcoming that geoscientists have been aware of and attempting to address for years. The title of a famous 2018 article published in Nature Geoscience sums up the problem: “No progress on diversity in 40 years.” The article emphasizes how the vast majority of geoscience doctorates go to white scientists, and despite an increasing number of PhDs being awarded in recent years, the proportion given to underrepresented minorities (URMs) has remained relatively unchanged since the 1970s. URMs include the races or ethnicities whose representation in STEM employment is smaller than their representation in the U.S. population, specifically “Blacks or African Americans, Hispanics or Latinos, and American Indians or Alaska Natives” per the National Science Foundation (NSF). Notably, Asians and Asian Americans tend to be excluded from this categorization. A more recent 2021 article authored by the UW College of the Environment’s very own Corey Garza, points to the fact that less than 9% of graduate students in the ocean sciences identify as a URM, and highlights several ways that BIPOC are turned away from the field. NSF statistics showcase how this issue persists today, revealing that 77% of the doctorates awarded in geoscience in 2023 went to white scientists and only 10% went to URMs. This issue is alive and well throughout the marine science programs at the UW, especially SMEA, which I can attest to firsthand.

It has been, frankly, stunning to see just how overwhelmingly white the program has been. I noticed the lack of diversity as early as the orientation, noting to myself the fact that I seemed to be able to count the BIPOC in the cohort on one hand. I repeated the process in every SMEA classroom that I entered during my first week and got the same results. Of course, I don’t harbor any distrust or resentment towards my peers – they have been supportive and kind and have a whole array of diverse experiences of other kinds. Besides, I’ve been in geoscience for long enough to expect to see so few BIPOC or to even be the only BIPOC in the room. And yet, I couldn’t help but lament the lack of visible diversity in the program, an essential piece to make the community a place for BIPOC to feel represented in. Honestly, I remain surprised that SMEA spaces were so white, especially given that younger spaces tend to be more diverse, even in geosciences. I was surprised enough that I decided to request admission data to see whether I was overreacting or if something larger was going on.

That’s how I learned that my observations were supported by statistics as well.

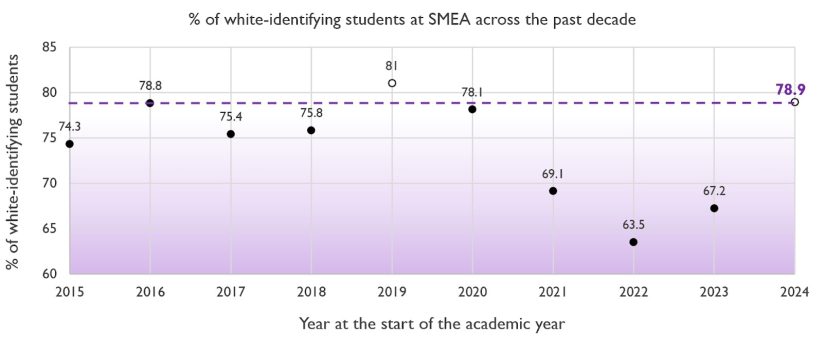

According to SMEA’s most recent admission data, 78.9% of current SMEA students identify as “white,” the highest proportion in the past five years, and the second-highest in the past decade, behind only 2019-2020 (Figure 1).

Naturally, this peak in “whiteness” has seen an accompanying reduction in racial/ethnic diversity. For the first time since 2019, there are 0 SMEA students who identify as Black or African American, Indigenous, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander students. These statistics, while demoralizing on their own, underlie a notable trend. The increase in the percentage of white-identifying students between 2023-2024 and 2024-2025 is the largest increase in the past 10 years and reverses three straight years of the program being less than 70% white-identifying.

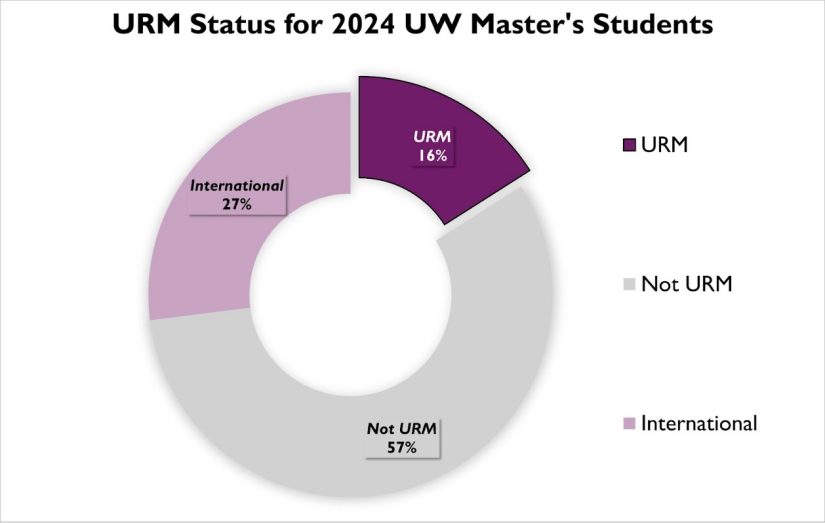

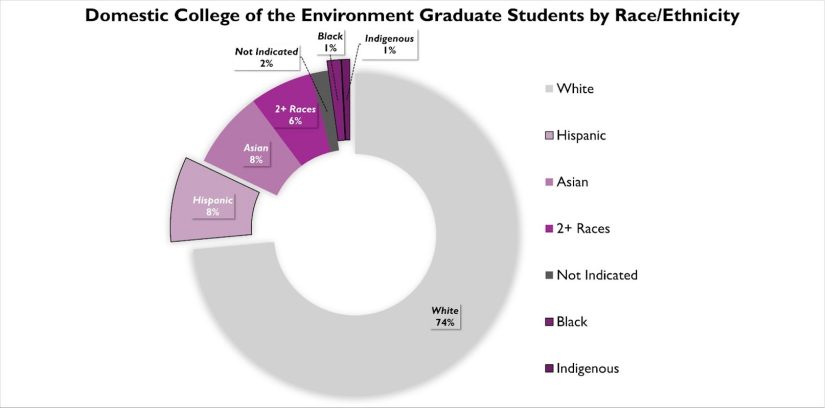

While the above statistics describe the program as a whole, it is evident that this trend is driven by my SMEA cohort, which includes only those who joined the program in 2024. Discounting one student who did not report their ethnicity, 88% of my cohort identifies as “white.” Comparatively, only 6% of my cohort identifies as a URM, far below the UW’s average of 16% URM enrollment across all master’s programs (Figure 2) and the estimated 11% across the other graduate programs in the College of the Environment (Figure 3). Amongst all current SMEA students, URM enrollment is below 8.5%.

Now, it should be acknowledged that these statistics are not infallible – they rely on self-identification and may be underreported due to a lack of nuance in the “multi-racial” and “International student” categories. They are also influenced by a marked rebound in enrolled students for the first time since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. But even allowing for error, the picture painted by this data is stark and should be treated as a warning of what could be true in more than just anecdotes.

Of course, it must be noted that SMEA is not the only aquatic science program at the UW facing these issues, something I know from experience as a graduate from the UW School of Oceanography. In fact, having been part of the College of the Environment since 2020, I have dealt with the specific issue of UW’s marine science programs lacking diversity for my entire college career. I dealt with the fact that there were no BIPOC mentors in my program because the School of Oceanography had no full-time faculty of color. I survived the College of the Environment’s Associate Dean of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion position remaining vacant for half of my degree, despite students’ outcry. And, with difficulty, I survived the lonely experience of having few (if any) peers who share my experience as a BIPOC marine scientist.

Strikingly, lack of diversity often went unnoticed because the issue did not affect my peers directly. As one of my fellow Oceanography alumni, Kristine Prado-Casillas attests, “being Hispanic/Latino, the isolation sometimes made me feel crazy… especially when my peers did not notice the lack of diversity around them.” Another of my BIPOC friends in the School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences reports the same about her program, pointing to the definite need for improvement in the department because the lack of diversity “really shows.” And seemingly, this issue has followed me from Oceanography to SMEA.

But the extent of SMEA’s struggle in increasing racial/ethnic diversity is particularly noteworthy, and not for lack of awareness. In 2019, (the “whitest” year of SMEA in the past decade), then-SMEA student Brian Tracey published a thesis describing how URMs at SMEA are disadvantaged due to their lack of “social capital,” and how that may inform SMEA’s historic lack of diversity. In that thesis, interviews with URMs in SMEA revealed feelings of isolation, and several students explicitly asserted that they “would not recommend SMEA to anyone,” revealing just how marginalized SMEA can make BIPOC feel. Something would have to change for BIPOC in SMEA to feel comfortable, and we would not have to wait long to see changes begin to take shape.

The racial reckonings of 2020, with both the Stop Asian American and Pacific Islander Hate and Black Lives Matter (BLM) movements reaching new heights, inspired students to begin reflecting on the need for increased diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives at SMEA. During Spring of 2020, students sent an open letter in solidarity with the BLM movement, and demanded numerous changes related to addressing historical inequities within SMEA. That letter seems to have been the impetus for many of the increased diversity initiatives since 2020.

Currents blog posts dedicated to DEI became more prevalent, with the summer of 2020 being dedicated to a series of articles on uplifting BIPOC voices within the marine world. Moreover, several tangible changes began taking place in the department, including the formation of the SMEA Diversity Forum (which acts as both an advocacy group and an affirming space for students from diverse backgrounds), increased inclusion of DEI-centric content in SMEA courses such as SMEA 500, and the formation of the SMEA Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) Committee (which enables dedicated effort from faculty towards DEI goals).

So, why is SMEA still so white?

And yet, 4 years later, after so much attention was given to the issue, SMEA is back to where it started. Our white population percentage is at its highest point since 2019’s cohort, reversing the seeming increase in diversity over the past 3 years. So, why is SMEA still so white?

It is, of course, possible that this year’s admissions were an outlier, or were inspired by the end of affirmative action, or even were due to the absence of an Associate Dean of DEI in the College capable of doing outreach to BIPOC communities for so long. But, it is also possible that there is evidence of a long-term issue.

Thus, I talked with Professor Ryan Kelly, who heads up SMEA’s admissions committee, wondering if the diversity issues simply stemmed from biases within the admission process. It is true that the admission committee has worked against siloing, for instance through the recent decision to include student voices on the committee. But Professor Kelly noted that, historically, more than 80% of both those admitted and those who applied identified as white. This indicates that the issue lies not just in who chooses to come to the School, but who chooses to apply in the first place. Intuitively, this makes sense, given the numerous systemic barriers preventing BIPOC from even reaching a graduate level degree, much less one in geosciences, much less one in geoscience communication or policy. Many BIPOC can simply not fathom a profitable career in geosciences or marine policy/communication, especially when they potentially have to pay for themselves to attend the program.

…but until we resolve the systemic issues barring BIPOC from wanting to enter the field at all, we may not see sustained and substantial increases in visible diversity.

However, this insight does put a dampener on SMEA’s current progress—SMEA can do as much work as it likes creating a safe space for URMs and increasing the presence of diverse perspectives in course content, and that work is positive and necessary in retaining and promoting diversity once it is here, but until we resolve the systemic issues barring BIPOC from wanting to enter the field at all, we may not see sustained and substantial increases in visible diversity.

Some of those systemic issues simply boil down to income—geosciences are notoriously seen as low-paying amongst the STEM disciplines, and environmental communicators/policymakers may have even less financial stability. For many BIPOC youth who face disproportionate levels of poverty, it can be impossible to commit to studying geoscience, especially if they have a family to support and are intimidated by the perceived high cost of field work and accreditations. A commonly-suggested remedy that SMEA could implement is increasing diversity fellowships and doing more work building relationships with BIPOC students to make SMEA somewhere both attractive and affordable. In fact, there is real potential that the increased diversity seen over the past few years stemmed from faculty engaging in targeted outreach and application help with specific BIPOC students.

Meanwhile, outreach in BIPOC communities about the opportunities in marine science remains subpar. Geoscience is already a field that not many kids have the chance to see futures in, and without targeted outreach to BIPOC youth, the racial gap will only grow. This withering will only be exacerbated if BIPOC cannot see people who look like them in positions of power. It is also possible that geoscience itself needs to be rebranded—for a long time, the community-centric aspects of the field have been undervalued compared to the pure science parts, which can be a major deterrent for BIPOC youth who want to give back to their communities. SMEA has the unique ability to support these altruistic, community-driven values that many BIPOC particularly value. Sitting in the intersection between natural science and social science, integrating community-based projects into the curriculum, and acting as a place for BIPOC to go to learn the skills needed for effective community work are all dynamics which can be emphasized to increase BIPOC interest in the program.

Each of these issues underscores the fact that SMEA is facing not just the need to reform itself, but to inspire system change, and I urge those in SMEA to commit to this work. Increased outreach about environmental science and communication to youth, from both a programmatic level and an individual level, is critical. Professor Kelly mentioned that this sort of endeavor is not universally seen by faculty and staff as something structurally embedded into their job. Instead, it is seen as something one must volunteer additional time and effort to accomplish. The disconnect between BIPOC youth and SMEA is a major issue, and must be addressed through dedicated time and funding if we want to have a sustained base of BIPOC students interested in and aware of the program in the future. SMEA must also emphasize the changes it has made, and be cognizant of continually improving the initiatives currently in place.

The College of the Environment must also play a role in this effort. A good initial step is the CoE’s recently announced renewed partnership with Seattle MESA (Math, Engineering, Science Achievement), an organization dedicated to providing URM, female, or economically at-risk middle and high school students with hands-on scientific experiences. However, it must be noted that this partnership’s current reliance on volunteers, rather than course credit compensation as in previous years, poses questions for long-term sustainability and equity.

Meanwhile, in the eyes of many BIPOC, including myself, the College of the Environment is sending mixed signals by renaming its Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion to the Office of Inclusive Excellence. The Office is currently hosting discussions with community members about this decision, but the change can easily be interpreted as an attempt to avoid backlash from the Republican administration, which has been extremely critical of DEI in schools and the federal government. In fact, this renaming follows a wave of DEI programs at universities across the country changing their names or disbanding altogether. Perhaps a name change is the best way to preserve programmatic funding for these initiatives, but as these initiatives theoretically become less visible to opponents, they may also be less visible to the community members who need them. Furthermore, as a person of color who is very aware of the increased potential for the oppression of at-risk groups under the current administration, it is incredibly demoralizing for the College to already succumb to baseless right-wing attacks. I can’t help asking myself, if the Office is willing to erase “diversity” and “equity” from its name before facing substantive pressure, then what might it be willing to cut when facing legitimate pressure? How can BIPOC, gender minority, and economically-disadvantaged community members fully trust that their institution will stand up for diversity and equity in practice if it won’t even stand up for the “diversity” and “equity” in its name? I hope that the Office of Inclusive Excellence remains a bastion for diversity, equity, inclusion, accessibility, environmental justice, and other values that are subject to far-right attacks, but only time will tell, and in the meantime, the College must ensure that minority community members are treated as equal, not expendable.

For SMEA though, some other solutions exist, including increased partnership with undergraduate programs at the UW such as the Program on the Environment (another program I graduated from) to demonstrate pathways for students at a younger age. From there, opportunities for high school and younger-aged students can arise, perhaps even modeled on the School of Oceanography’s High School Ocean Intern summer program or the Department of Earth and Space Science’s (student-driven) “Rockin’ Out” K-12 outreach program, both of which allow youth to learn more about what a career in marine science could look like. By presenting diverse youth with these options, and making justice-centric marine science a viable option, we may see the system change needed for reform.

I believe everyone within the program needs to exhibit a willingness to push for reform, both within SMEA and in our society, listening to and uplifting the demands of those already fighting for change. This is the most important way that non-BIPOC community members help to champion racial/ethnic diversity.

And, most simply, the SMEA community must remain willing to confront people and systems on their oversights and shortcomings, whether it is a peer who has not thought about the lack of diversity in the program because it does not affect them or a systemic issue of a cohort being 90% white. We cannot afford to stop talking about these issues, even when it is uncomfortable, because that is how movements die out and progress is reversed.

Years ago, when I was still on the first steps towards starting my professional journey in marine sciences, I sought advice from one of the few Filipino geoscientists I knew about how to leave a legacy that would enable other Filipino marine scientists to join us in the future.

She told me this: “We should not be content with simply propping open the door behind us – we must aspire to entirely destroy the door frames responsible for presenting closed doors to so many in the first place.”

If we are successful in destroying those door frames, then hopefully, sometime soon, BIPOC marine scientists entering the doorways into their SMEA classrooms won’t feel so alone.

“We should not be content with simply propping open the door behind us – we must aspire to entirely destroy the door frames responsible for presenting closed doors to so many in the first place.”