Who do we become when we leave home? On seasonal change, the coast of Maine, and moving away

There is sand for miles and miles and miles. Dark and gleaming on this blustery spring day, the sand sinks softly under my feet as I walk the beach up and down. I have on my foul weather jacket – bright red with a neon reflective hood that velcros up to my chin keeping out all the pelting rain. I know the ocean. I know the throes of seasonal change, but I feel like a stranger on this western coast. If I yell, the wind will whip the words out of my mouth, send them on down the shore to be pulled out to sea and left adrift amongst the creatures of the deep. All I can hear from here are the endless crashing waves that pour white foam up to my toes, leaving little bubbles that sizzle and disappear as the tideline recedes with each passing moment. I want to fall in love with this ocean the way I have fallen for another, but something keeps me second guessing myself. Where are the black-capped chickadees? Where are the cobblestones, and Ascophyllum covered boulders, and fog so thick I feel like I am swimming through it?

Listen to this story I am about to tell you: it is March of last year and I am mourning. The kind of mourning that only comes from big change and the edge of a precipice that you have come up against before you are ready to make the jump. The honesty in this moment is unbearably uncomfortable. Who I am is one long day after another; a trial run of new ideas and chapped lips from what I am beginning to believe will be the longest winter of my life. The edge of town is so far away and every time I think of leaving, the border seems to shift just out of reach, like I am frozen in time. And yet, I shed a layer. My ears turn bright red with the chill, I am a heathen for this risky business of dancing with temperatures that freeze my shower-damp hair as I run out the door. I know this weather the way I know the tide charts or how long to knead a loaf of bread.

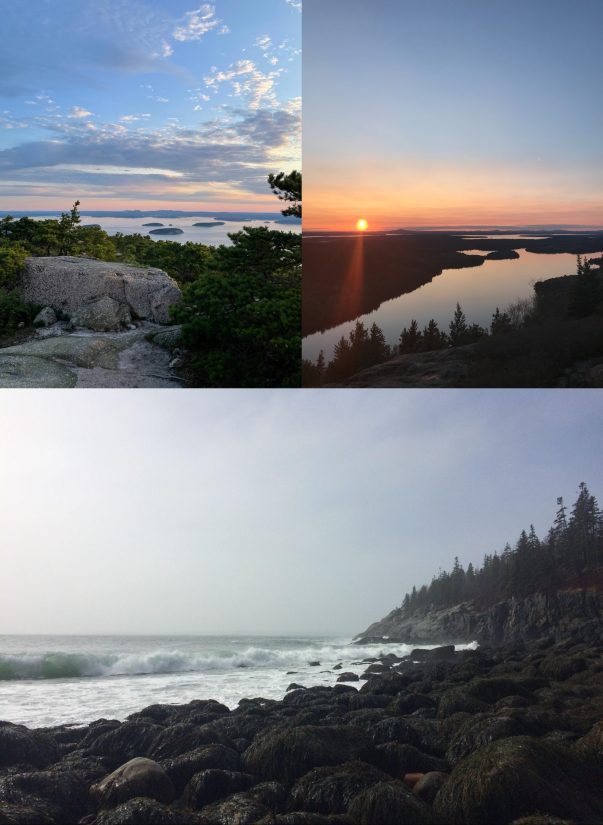

This is my version of Maine. I know the outer islands better than the names of my relatives, and I know what spring sounds like. It’s clawing your lump of a body out of the ruins of an old, abandoned granite quarry to crack the marsh ice with stones from shoreside. It’s reminding a parent to send their child to school with clothes they don’t mind getting mud-covered. It’s the way a child’s curiosity draws them into the tidal flats, and the way a child’s yell is the very mirror of the call of a laughing gull. It is March of last year and I make the journey home each evening awaiting the peepers. (1)

March: Spring Peepers

A peeper is a sure sign of spring in Maine. They’re little frogs, only about the size of a paperclip and I’ve never even seen one. Invisible to the eye but a symphony to the ear, they are an indicator species inextricably linked to a change in seasons. Their tiny bodies lie in marshy wetlands, small ponds and in the leaf litter of forest floors as they emerge from winter hibernation and enter mating season. And it’s that mating season that ushers in a new soundtrack to coastal evenings.

A spring peeper’s call is like a cricket but louder and unrelenting. Soft chirps hug a louder, higher pitched shriek that softens in the glow of golden hour, dusk and then the blue evening period before the milky way emerges over the harbor. Males group together, singing, to attract a mate. The louder the call the more likely a male will be selected by a female so the spring peepers coat the woods with their voices swelling into crescendos that mimic the whistle of my kettle as the water comes to a boil. (2)

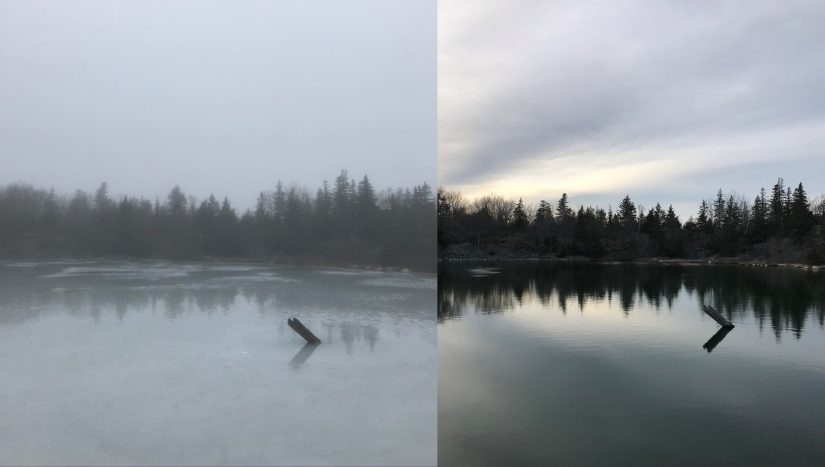

In March, I walk the meandering Clark Island trail over and over noting each time how much of the ice has gone out in the old quarry at the end of the trail

This has come to be another place I belong to. On the precipice of spring, the island is devoid of any people, especially at golden hour when I frequent the preserve the most. Instead, I hear the peepers as I walk down the old road, past an ancient, rust-covered tractor, past the old fruit trees, past the stone foundations of buildings long gone, a relic from when the island used to be a bustling granite quarrying site. (3)

April: Turkey vultures

In your twenties you are almost always a stranger to someone or some place. At least these are the observations I have made. I live out of my car, I move houses every six months, I am always in a state of transition. I see things pass me by like tall grass in a meadow from the passenger seat. What is true no matter where we turn? What holds constant in turmoil? I look to the sky each evening and it’s all clouds, but I know that somewhere else, someone is watching the best sunset of their life. I think: that is comfort.

Keep listening. It is April now and I turn my face towards the sky. Smooth sun hits my skin, and I can feel it through my body like the first sip of a hot drink. Mud season, turkey vulture season. Today I am lifting one foot in front of the other as I make my own seasonal migration up Sargent Mountain in Acadia National Park for the first time this year. When I was a child, Sargent used to seem untouchable. Her bald summit towers over the nearby peaks of Parkman, Bald, Gilmore and Cedar Swamp while Cadillac Mountain sits only a hundred or so feet taller off in the distance. Now, I can’t seem to spend enough time learning her every nook and cranny. I have hiked every trail up Sargent. I have seen her in snow and peak fall foliage, eaten many summer lunches looking out across the outer islands and it’s here where I see the first turkey vultures return. (4)

A mere half century ago, turkey vultures were not on any birders’ radar when they went out to observe the first spring migrants into Maine. Instead, red-winged blackbirds and common grackles welcomed spring on their small wings. In fact, turkey vultures were not known to really be a Maine species. In “Maine Birds,” published in 1949, Ralph Palmer lists only 12 records from 1862-1944 of a turkey vulture sighting in Maine. Now, as I stand near the Sargent Mountain summit sign, I am almost level with one soaring gently despite the swift breeze that cuts my cheeks raw and makes me yank my hat lower onto my head. From sea level they are easy to spot with dark brown wings that create a shallow “V” shape as they fly smoothly, seemingly rocking from side to side. But from the height of this peak, I can see its entire body – the stout neck and bald red head, the white of the underwing is more pronounced from up here too.

In December I did this same hike except it was cold and snowy and I was surrounded by people I loved, and we were nervous about the sun setting on us before we’d make it back to the car. I remember being close to breaking out of the tree line when we stumbled across the fresh carcass of a white-tailed deer, picked clean, antlers still attached to the skull, skeleton neatly intact. In that moment of discovery, I wanted to pull off my gloves and run my hands over the bones, to understand a life for another life, the mysteries of the woods pressing in, to wonder and be okay with just wonder. Now, I wonder again, where have you been my first-of-the-year turkey vulture? Where have you come from?

Who do we become when we leave home?

Oh, all these moments add up to something, right? The sights and sounds of spring muddle about in my wintered-over mind pulling it out of its own version of hibernation into something that resembles vigor and joy, so much lush new growth worth nurturing. For over twenty years I have lived on this rocky Maine coastline waiting for the peepers and the vultures, observing cyclical patterns of life and death, wading into too-deep waters just to “turn… again home.” This version of myself is familiar. But who do we become when we leave home? How do we hold on to the places we belong to?

In Seattle now, I bring my Mary Oliver book on the 44 bus as my morning commute companion. I read “Whelks” over and over and underline all my favorite parts until it becomes one giant penciled mess. I start to say yes to new adventures and put fenders on my bike tires so that even on these gray days I can bike around the city. I get better at driving my manual car up and down the city’s steepest hills and take comfort in my early morning runs around Green Lake. I call my mother three times a week and send lengthy handwritten letters to a friend who always picks up when I call. She sends me back sound clips of this years’ spring peepers. I hold last year’s mourning somewhere but now I climb up and up into another universe until I am the turkey vulture, silently pulling behind me so much lush new growth worth nurturing. (5)

Key to soundbites above

- The loud calls of a flock of laughing gulls from a beach that seem to mimic the yells of children running in the mudflat.

- The calls of the first spring peepers of 2021 as heard from the deck of the author’s apartment overlooking a small pond.

- As spring thaws, the sounds of pond water pushing up against the gently frozen surface create a creaking sound that is haunting.

- The rushing water of Maple Spring that parallels the Maple Spring Trail up Sargent Mountain. In April, the water rushes loud and swiftly with snowmelt.

- The footsteps of the author as she hikes up the bald summit of a mountain in Acadia National Park. Soft birdsong can be heard in the background.