What even is biodiversity, anyway?

Of all the weird quirks and qualities of language, I always get a kick out of envisioning connotation as some sort of sublime magical power. Woven into every word is a panoply of emotions, history, and cultural associations converging to sculpt the particular shape it impresses into the mind. When two entries in a dictionary overlap in definition, connotation is what makes each word a unique encounter at the intersection of all of those feelings and imagery that tend to orbit it. The choice to use one word over another similar word is part of the craft of steering these mental reactions in one direction or another, almost like a miniature form of mind control. My description of a person you’ve never met can enchant your perception of them with choices like eccentric over weirdo or touchy rather than sensitive. I can describe a journey across the steppe and conjure a flash of imagination transporting a listener to the vast stretches of Central Asia. Yet, if I mention a journey across the prairie, that phrase instead draws on the imagery of frontier stories like Little House on the Prairie to create idyllic scenes of flowers and wind-touched grass.

This power is constantly at play in the war of words that is political discourse. From connotation comes the ability to frame a subject, and this can be the difference behind rhetoric’s ability to stir action or inspire a yawn. Whether for good or ill, connotation has a hand in building the rhetoric that spurs people to plant trees or mobilize armies. It can also change over the years, giving different generations wholly unique conceptions of the same word. For both of these reasons, it’s a property worth paying attention to in each of the lofty, abstract words that bear weight on our lives.

In recent years, I’ve been grappling with a single word that influences every type of life: biodiversity. It is inescapable in both the ecological sciences and the public’s conception of humanity’s fraught relationship with nature. As an environmental cause célèbre, it’s as widely known as climate change. Calls to promote biodiversity set up the architecture of green agendas such as the EU’s Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and prop up institutions like the WWF and IUCN. Billions of dollars flow, and millions of acres of land are placed under protection in its name. Most people have encountered it in their science education or any media about wildlife. You would be bound to hear of biodiversity even if you lived under a rock- and then take notice that there’s plenty of it crawling and squirming and slithering and living under there too. Wherever a sense and value of nature seems to become apparent, biodiversity seems to follow.

When I got involved in a study that required me to track a measurable amount of biodiversity. I assumed that the concept would be straightforward to define and quantify. Instead, like that stone flipped over, trying to shed some light on biodiversity reveals a menagerie of potential meanings, each scampering to escape in a thousand different directions before you can catch one. Despite all of its momentum, the idea of biodiversity remains strangely elusive, championed by millions but interpreted with alarming inconsistency.

So how did we get here?

The history of the idea of biodiversity provides a few insights into why its meaning remains so difficult to pin down. Most definitions unite around a sense of variety inherent in nature. After all, the components bio- and diversity point to it at least having something to do with life and something to do with variability. Yet views of variety in the natural world have long been shaped by shifting scientific, cultural, and philosophical perspectives.

Intellectual interest in this topic goes as far back as the ancient Greeks pondering the idea of distinct forms themselves and what their purpose was in the structure of reality. Plato’s Timaeus praised nature’s variety as an essential piece of divine craftsmanship:

“Since the God wanted nothing more than to make the world like the most beautiful and perfect of the intelligible things, he made it a single visible living thing, which contains within itself all of the living things whose nature it is to share its kind.” (Timaeus 30d)

Somewhere further down the line, you can see this view trickle down to schools of medieval and early modern Christian thought, where prominent leaders like Saint Francis of Assisi saw all of this biological variety as a theophany, an earthly manifestation of God’s goodness. Yet since this divine plan had apportioned an exact role and purpose to each living thing, the exact amount of variety was seen to be fixed. Concerns about biodiversity were not in view because extinction was seen as inconsistent with this order. When specimens like the Irish Elk (Megaloceros giganteus) and the Giant Ground Sloth (genus Megatherium) turned up, scientists embarked on futile missions to discover remnant populations until the growing fossil record made it impossible to argue that all of these organisms were still hiding away somewhere. Mounting evidence eventually allowed extinction to be accepted as a biological fact in the centuries to come.

If the era before the late 19th century of this saga could be defined by the progressive understanding that extinction was possible, the defining realization of the 20th century was that humans were making extinction inevitable. By 1914, humans in North America had eradicated the Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), a species that was once so numerous that a gunshot lazily pointed at an overhead flock could bring down several birds. The extinction of other prominent or iconic species, like the American Bison and Whooping Crane, looked soon to follow. Legislation and political action tailored to combat these extinctions, like the Lacey Act (1900), Migratory Bird Treaty (1918), the Endangered Species Act (1973), and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (1972), had their sights set mostly on conspicuous vertebrate systems in decline. Yet across biological disciplines, the thread of concern was the same: where there was human development, there was a noticeable degradation of the total plant, animal, fungal, and microbial diversity.

In response to wide-scale environmental changes, the new discipline of conservation biology emerged through the 1970s and 1980s. However, biodiversity still didn’t enter into the scientific vocabulary or environmental vernacular serendipitously. The word was a neologism, created by biologist Walter G. Rosen for The National Forum on BioDiversity held in Washington D.C. in 1986. The word, like the forum itself, came to be a focal point for scientists, politicians, and the public to rally around the cause of preventing species extinctions. Yet Rosen had only created the term as a shorthand for ‘biological diversity’, and the National Academy of Science had only intended for the event to be a press conference to inform Congress of this issue. The Academy, with a reputation for objectivity and solemnity to be upheld, had continuously expressed its concerns to the organizers that the event would turn into an avenue for advocacy. Its worst fears came to fruition when the value of biodiversity came into the conversation. A slew of eminent biologists came out of the shadows to argue passionately about its importance. Experts across fields of international development, economics, ethics, and even theology joined the discussions and weighed in on where they saw biodiversity’s value. Recorded footage of the event was distributed to turn the event into a media spectacle. Biodiversity had taken on a life of its own, escaping the strict confines of a scientist’s technical diction and into the embrace of all who cherished the uniqueness of Earth’s lifeforms and looked at their extinction with a sense of despair. Asked later about the creation of the term, Rosen (somewhat wryly) remarked:

“It was easy to do. All you do is take the ‘logical’ out of ‘biological’. To take the logical out of something that’s supposed to be science is a bit of a contradiction in terms, right? And yet, of course, maybe that’s why I get impatient with the Academy, because they’re always so logical that there seems to be no room for emotion in there, no room for spirit.”

Even as conservation biology matured as a scientific discipline and biodiversity gained an exalted status in the environmentalist’s lexicon, its exact meaning has remained ambiguous. A 1996 study by DeLong reviewed as many as eighty-five institutionalized or expert-derived definitions without coming across “a formal semantic basis for the meaning [of biodiversity]”. For his book The Idea of Biodiversity: Philosophies of Paradise, David Takacs gathered definitions from interviews with the scientists at the helm of the Forum on BioDiversity and still found that their conceptions were scattered. Some gave earnest (but disparate) attempts to recite the kind of definition you would see in an encyclopedia. Others shared what their idea of biodiversity is while being upfront that others may take a different view. A couple claimed they don’t have a definition or refused to answer—biodiversity, to them, was simply a buzzword. Upon hearing the question, one interviewee laughed.

Although it’s been several decades since the word’s inception and these interviews and studies made to pinpoint its meaning, scientists are no closer to converging on a universal definition of biodiversity. Issues abound with both the bio- and the -diversity components: What level or characteristics of life are being included in the term, and how much difference between these units of life can actually count as a distinction?

Scale is perhaps one of the most difficult elements with which those concerned with biodiversity must grapple. The most inclusive advocates of the concept encompass biological variation from the most granular genetic inconsistencies of individuals within a population to the variety of distinct ecosystems within a landmass or seascape. Each definition represents a choice of how wide of a net it wants to cast, but even the most seemingly broad definitions slim down once someone tries to operationalize them in some way. Counting species is a difficult enough project, especially in tropical regions—how often is it also feasible to capture the genetic variation within all of those species that are documented?

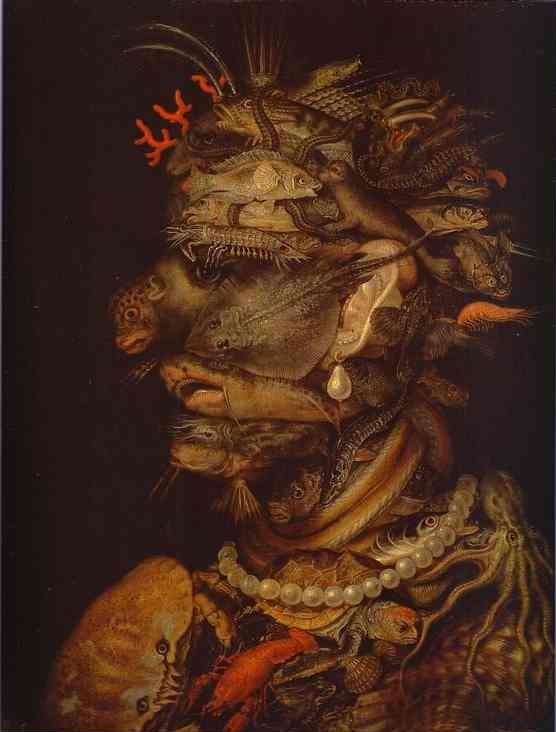

Species is the most frequent focal point of most definitions, and some definitions of biodiversity only look at it as a tallying-up of anything that can be given a scientific name. Within the iconography of biodiversity, it makes for an incredibly powerful poster child. An image of a reef thick with swarms of colorful, oddly shaped fishes creates a vivid, in-your-face display of nature’s complexity, and a collage of charismatic species will have one character or another that is bound to strike a particular emotional chord with its viewers. When it comes to environmental restoration, replenishing subspecies variation or restoring important ecosystems in a landscape mosaic is more fathomable than replacing a lost species. Most people know that once a species is gone, it is gone forever.

Though the species-only view is not a holistic view of the variety present in the natural world, it is often embraced because it seems to be an easily noticeable embodiment of diversity. Side-by-side, the appearance of unique species is usually different enough even for non-scientists to know it when they see it. This should make species straightforward to track and count, but narrowing down to species as the only level of variation doesn’t make the concept any less elusive or inconsistent. If biologists cannot agree on what the definition of a species is, then how is species richness going to be a stable foundation for measuring biodiversity?

Thanks to the complications of biology, no hard-and-fast rule is without an exception somewhere in the natural world. Thus, the diversity of the natural world is complicated by the diversity of how many species concepts are out there. Of these concepts, the most prominent, the biological species concept, is also the most challenged by counterexamples. Darwin himself was critical about using sterility or fertility to draw the lines of what is and is not considered a species, dedicating a chapter of The Origin of Species to outlining the idea of reproductive isolation. If trying to determine what is and isn’t a species isn’t enough of a herculean task for plants, fungi, and animals, it’s a completely different ballpark in the microbial world, where most organisms reproduce asexually and exchange genetic material with unrelated organisms.

Just as species brings its cargo of uncertainty to the biodiversity concept, zooming out to encompass ecosystems also invites a host of new questions. An ecosystem is more than just the sum of each of its component species—it is also the skein of relationships between each species as well as between the biotic and abiotic world. But many experts have a distaste for incorporating these functional processes and nonnatural features. Adding in all of that extra complexity complicates any effort to measure biodiversity or set clear biodiversity conservation goals. The broader the definition of biodiversity, the greater the risk it becomes diluted with the rest of the world’s environmental lingo. After all, would the broadest possible definition of biodiversity, with all the abiotic and functional characteristics of an ecosystem, be any different than the words nature or ecology?

Even subspecies levels (like population or genetic biodiversity) also grapple with the degree of difference is meaningful enough to draw a line between evolutionary significant units. These judgments can be culturally and personally relative or operationalized on economic or aesthetic considerations. Proving that a crop variety is distinct enough to deserve protection under US patent law requires that the strain meets a list of legal criteria–thus leaving the question of whether an entire lifeform is a unique being to the arbitration of the court system and the political and economic forces that animate it.

But these questions of meaningful difference don’t only come from legal frameworks or scientific publishing– they are also present in the ways that people across cultures have long recognized and categorized the natural world. Though the scientific study of taxonomy– the organization of lifeforms into distinct species, families, and other units of classification with Greek and Latin names– constantly evolves and corrects itself in the light of new information, only recently have scientists started to pay any attention to folk taxonomies– the ways that cultures recognize different species or subspecies distinctions based on traditional ecological knowledge. For example, ecologists trying to make sense of the variety of Amazonian Cecropia trees found that the local Matsigenka peoples already had names for the species that were undescribed to science, as well as sub-group names for existing species that corresponded to distinctions that scientists found in later field seasons. Yet, even in the same place, different peoples and cultures with an intimate understanding of the ecosystem may still make these distinctions in ways that don’t align with one another.

Non-native species cause another headache: Should they be considered a part of a location’s biodiversity? The introduction of new species to new places has always been a part of the history of the natural world, and the introductions abetted by humans have a complicated suite of effects. In many instances, they usher in invasive species like the well-known rats, lionfish, cane toads, or starlings. In others, their presence can have more complex effects, occupying newly opened niches and providing new ecosystem services. Feral donkeys and horses, for example, are a controversial presence in the American Southwest since they can mow down existing plant diversity and compete with endemic animals for food sources–yet they also can engineer new sites of water availability by digging wells into the groundwater. The presence of their hooved, plant grazing ancestors was once an influential part of this ecosystem that was lost when many of North America’s large mammals disappeared 11,000 years ago–yet before considering them as a replacement, it’s also worth considering that the predators capable of controlling their populations (like mountain lions) have also disappeared from most of the ecosystem.

Although occasionally people avoid it by clarifying that their focus is on “native/endemic biodiversity”, this debate ventures into some fundamental questions about what biodiversity is trying to protect. Is protecting a place’s biodiversity about maintaining the historic appearance of its ecosystem? Or is it about ensuring that the place can continue to harbor a variety of life, even if it will predictably be influenced by human contact and climate change?

Of all the definitions that I have encountered, I find myself most keen to embrace the ones that accept that biodiversity can adjust itself to suit the situation at hand. This word has a rhetorical vitality that few other environmental phrases possess, largely because it can cast a wide net over so many aspects of the natural world, as well as the values and emotions tied into protecting it. Each person who hears the word biodiversity forms its image in a shape relevant to their own experience—whether it’s a beloved species, a favorite landscape, a web of ecological connections that fascinates them, or a sense of wonder at the intricate machinery of nature. Even though this conception differs from person to person, each definition of biodiversity will encompass some cherished aspect of nature.

The impulse to define biodiversity is understandable, and in some settings, essential. We need metrics to measure progress and track loss when it comes to species extinction and the homogenization of natural spaces. Yet biodiversity as a whole can certainly survive the multitude of ambiguities and uncertainties packed into its definition. Its strength lies not in how precisely people define it, but how deeply people feel its importance.

The following sources may be behind a paywall, please contact the Currents Editor-in-Chief for access:

[1] DeLong, D. C. (1996). Defining Biodiversity. Wildlife Society Bulletin (1973-2006), 24(4), 738–749. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3783168

[2] Ereshefsky, M. (2022). Species. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2022). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/species/

[3] Faith, D. P. (2023). Biodiversity. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/biodiversity/

[4] Gould, S. J. (1977). Heroes in Nature. In Ever Since Darwin: Reflections in Natural History.

Jr, G. H. S., & Uzarralde, M. (n.d.). Rain Forest Habitat Classification Among the Matsigenka of the Peruvian Amazon. Journal of Ethnobiology.

[5] Oksanen, M., & Pietarinen, J. (Eds.). (2004). Philosophy and Biodiversity (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

[6] Rubin, E. S., Conrad, D., Jones, A. S., & Hervert, J. J. (2021). Feral equids’ varied effects on ecosystems. Science, 373(6558), 973–973. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abl5863

[7] Scherber, A. (2017, February 14). Flocks that Darken the Heavens: The Passenger Pigeon in Indiana. The Indiana History Blog. https://blog.history.in.gov/flocks-that-darken-the-heavens-the-passenger-pigeon-in-indiana/

[8] Schorger, A. W. (1955). The passenger pigeon, its natural history and extinction (pp. 1–456). University of Wisconsin Press. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/288413

[9] Takacs, D. (1996). The Idea of Biodiversity: Philosophies of Paradise (1st ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

[10] The Deep History of the Sonoran Desert. (n.d.). Retrieved April 7, 2025, from https://www.desertmuseum.org/books/nhsd_deep_history.php

[11] Youatt, R. (2015). Counting Species: Biodiversity in Global Environmental Politics. University of Minnesota Press.