The North American Amazon: A Cradle of Biodiversity in Need of Protection

When I think of the Amazon rainforest, located primarily in the northern regions of Brazil, I see images of deep lush green trees and vines bordering a river filled with an incredibly diverse array of animals. But it always seems like a distant place, inaccessible and far away. The United States, however, has an “Amazon” of its own. Tucked deep in the American South, Alabama boasts one of the most ecologically and biologically diverse river systems in the world. The Mobile-Tensaw Delta is a National Natural Landmark and covers about 300 square miles (192,000 acres) of Alabama. This 45-mile long swath of Alabama includes open water, marsh, swamp, and bottomland forest habitats.

Having grown up and done my undergraduate work in Virginia and South Carolina, I have spent a great deal of time in the American South, and when I picture it I don’t have the same sense of lush biodiversity as the Amazon rainforest. However, the Mobile-Tensaw Delta is home to a whopping 1,071 identified species, 571 of which are animals. The delta is crucial for the survival of many endemic species, like the Alabama red-bellied turtle (Pseudemys alabamensis) and the Red Hills salamander (Phaeognathus hubrichti). Additionally, the concentration of certain organisms like oak trees, mussels, and crayfish is higher than anywhere else in the United States. The delta boasts the highest concentration of turtle diversity in the entire world, with 18 species. Alabama is ranked as the No. 5 state in the U.S. for biodiversity by The Nature Conservancy.

Beyond the clear biological importance of the area, there is a strong social and cultural history in the region. Evidence of human habitation as long as 5,000 years ago has been found in the area. Bottle Creek and Mound Island are some of the oldest Native American cultural sites in the United States, with evidence of sustained occupation of the area starting in 1250. Mobile is one of the oldest European settlements on the Gulf Coast, predating the more widely known New Orleans, and was an important trading center for early European settlers and indigenous peoples. To this day, the Poarch Creek Indians, the only federally recognized tribe in the state of Alabama, reside on their ancestral lands 57 miles outside of Mobile.

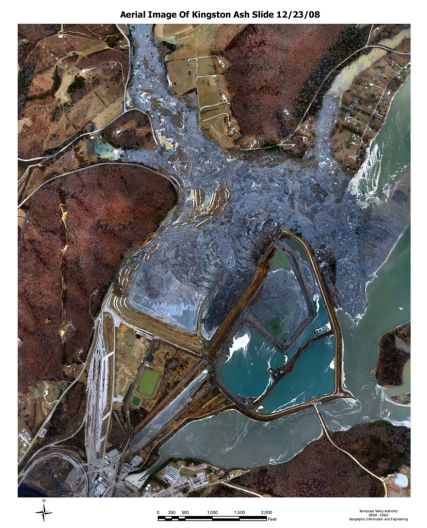

While the biological and cultural significance of this region is clear, anthropogenic stressors such as pollution, climate change, and development pose substantial threats to its survival. Similar to issues salmon face on the West Coast, dams have constricted fish migrations in the region and limited habitat for many species. A major threat to ecosystem health includes coal ash, a toxic byproduct of coal-fired electric plants, that contains chemicals such as arsenic, lead, and mercury that are detrimental to ecosystems. The James M. Barry coal-fired electric plant, 25 miles north of Mobile, has dumped over 22 million tons of coal ash into open-air storage ponds since 1965. These storage ponds are prone to leaching into groundwater and have the potential to spill directly into the river if a storm causes a storage pond to breach. A 2008 coal ash spill in Kingston, Tennessee proved to be a bleak example of how devastating coal ash spills can be. Dozens of clean-up workers who were exposed to the toxins died, and in the decades following the disaster, more became sick. Of all listed extinctions in the United States since the 1800s, nearly half were species from the Mobile-Tensaw Delta. The combination of threats to the ecosystem has not gone on without environmental consequence.

But hope is not lost for this overlooked gem. Conservation groups like Mobile Baykeeper, Southern Environmental Law Center, and the Nature Conservancy have been working tirelessly to place protections for this biodiversity hotspot. In early 2024, the Holdfast Collective (a charitable grant arm of Patagonia) donated $5.2 million, allowing The Nature Conservancy to make a $15 million deal to acquire an 8,000-acre plot in the Mobile-Tensaw Basin. The Nature Conservancy is calling the plot the “Land Between the Rivers”, and has put a lot of effort into promoting its conservation efforts in the region. About half of the delta’s acreage is under some kind of federal, state, or local protection; this alone should be considered a major win for the ecosystem.

The next step is protecting the edges of the delta, those vulnerable areas where people aim to build houses or developments to capitalize on the incredible water views. Both the late E. O. Wilson, a famed Harvard biologist and conservation advocate, and Ben Raines, author of “Saving America’s Amazon: The Threat to Our Nation’s Most Biodiverse River System”, emphasize that the future of the delta depends on maintaining the health of the swamps and marshes where the land meets the water. While there is always progress to be made and work to be done when it comes to conservation, biodiversity advocates should celebrate these small wins too when they come. We can rest assured there are people and organizations out there fighting every day to protect the American Amazon.

Note: Contact Currents Editor-in-Chief for access to:

Renkl, M. (2024, Feb 10). A Glimmer of Hope for Environmental Time Bombs: [Editorial Desk]. New York Times https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/glimmer-hope-environmental-time-bombs/docview/2924130879/se-2