The Fate of Frenchman Bay: a Contentious Battle Over Downeast Maine’s Marine Resources

Visible from the mountain tops of Acadia National Park, Frenchman Bay is both a recreational haven for visitors from across the globe and the economic and sociocultural backbone of Maine’s Downeast coast. Last year, seemingly overnight, a fight over this vital coastal hub began. Driveways and lawns across northeastern Maine have sprouted signs that declare, “Keep Frenchman Bay Fish Factory Free” and “Stop Industrial Scale Aquaculture.” Often touted as the future of sustainable seafood in Maine, the growing aquaculture industry appears to have hit a roadblock in this far-flung corner of the United States.

“Often touted as the future of sustainable seafood in Maine, the growing aquaculture industry appears to have hit a roadblock in a far-flung corner of the United States.”

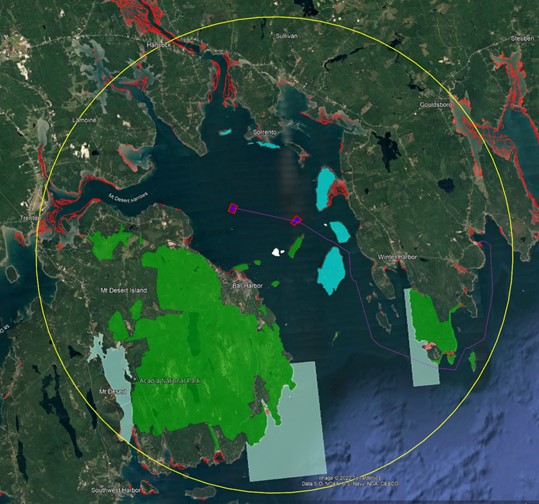

American Aquafarms, a company backed by Norwegian investors, has applied for permits to construct two 60-acre Atlantic salmon farms in the middle of Frenchman Bay. According to the application, at full operational capacity the farm would contain a total of 30 pens and produce 66 million pounds of salmon per year, approximately double the amount farmed annually across the entire US. If completed, it would be one of the world’s largest industrial salmon farms, covering the equivalent of 16 football fields.

Located in Hancock County, Frenchman Bay is home to several unassuming yet vibrant fishing villages. Every summer, people flock to the area to hike, kayak, camp, fish, and vacation. Aside from tourism, one of the biggest economic buoys in the region is lobstering. The lobster fishery in Maine brings in upwards of $400 million of revenue annually, roughly 80% of the value of all seafood caught in the state. Yet the industry is in a precarious situation. According to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Gulf of Maine is currently warming faster than many of the world’s oceans. Warming threatens fragile lobster populations, and with them, the maritime culture of the coast.

In the face of climate change, much of Maine’s leadership is seeking ways to economically diversify. For coastal communities, this may involve an increase in aquaculture. Governor Janet Mills’ 10-year economic development plan highlights the potential for growing the state’s existing land-based aquaculture industry as well as investing more resources into ocean-based projects, such as American Aquafarms’ proposed project. Proponents say such efforts can produce sustainable seafood, create well-paying jobs, and support the economy. American Aquafarms maintains their new project will benefit Downeast communities and economies. They hope to increase domestic production of seafood to support a move away from international imports, as well as create career opportunities amid recent declines in wild fish stock. However, as the battle over Frenchman Bay illustrates, integrating such projects into existing coastal economies and communities may be more difficult than anticipated.

Already faced with looming uncertainty, change, and concern over preserving existing ways of life, many citizens are not swayed by the promise of jobs and sustainability. The community response to American Aquafarms’ lease application, submitted to the Maine Department of Marine Resources in March of 2021, was immediate. A coalition of nonprofits, businesses, citizens, and scientists penned a letter to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to request an Environment Impact Assessment and express their vehement opposition. Soon after, the superintendent of Acadia National Park publicly shared a list of concerns associated with the scale of the project, its potential impact on visitor experience, and the overall ecological health of the park. In June, all 26 commercial lobstermen in Bar Harbor signed a letter objecting to the project and in August, a flotilla of over 100 commercial and recreational boats paraded across Frenchman Bay in protest.

“Resistance to industrial development of Frenchman Bay is all but unanimous, pointing to the collective sense of place-based identity engendered by every individual’s unique relationship to the bay.”

The fast and ferocious mobilization of local stakeholders has drawn attention from far and wide, with international nonprofit Oceana joining the chorus of voices opposing industrial-scale finfish farming in Frenchman Bay. In order to resist American Aquafarms from settling in the bay, a coalition of commercial fishermen, conservationists, recreational boaters, and summer residents formed Frenchman Bay United. Historically, these constituents have rarely aligned on an issue with such unity, with conspicuous divergence in political opinion being the norm. However, in this case, resistance to industrial development of Frenchman Bay is all but unanimous, pointing to the collective sense of place-based identity engendered by every individual’s unique relationship to the bay.

Downeast Maine is a unique place. It is rugged, beautiful, and complex, dominated by rocky beaches, forest, and an enduring sense of community and resilience. The rural expanse of Hancock and Washington Counties make up the northeastern most coastline of the state. Despite being home to one of America’s most popular national parks, Acadia, the region is remote and largely undeveloped. Discussing her recent book, Downeast: Five Maine Girls and the Unseen Story of Rural America, author Gigi Georges wrote of Downeast Maine: “Even in the toughest of circumstances—including childhood poverty, limited economic opportunities and opioid addiction—rural-dwellers in these parts sustain themselves and each other through robust community networks, deep connections to the land and sea around them, and optimism about the future of their hometowns.” American Aquafarms may not have considered the strength of social capital inherent to the deep-rooted communities of Downeast when they decided on Frenchman Bay for their gargantuan project.

The list of concerns from stakeholders spans issues of scale, untested technology, ecological damage, and threats to working waterfront lifestyles and livelihoods. While there are a few smaller-scale aquaculture ventures in Frenchman Bay–including one of the country’s only organic seaweed farms–it is the sheer size of the American Aquafarms project that elicits concern from community members and scientists. In fact, the project is too big to be allowed in the company’s home country of Norway, which has far stricter rules and regulations for salmon aquaculture than Maine. A project of this size would produce huge amounts of waste (in total, the equivalent of three times the amount of sewage discharged by Manhattan), generating concern for potential pollution. According to American Aquafarms, their waste disposal technology and cutting edge “closed pens” would eliminate much of the risk associated with contaminated effluent and disease, ultimately making salmon farming a more safe and sustainable venture.

However, it remains to be seen whether American Aquafarms can successfully scale up the technology, as it has yet to ever be used at a farm of this size or for growing salmon to adulthood. In fact, in 2020, a company in Canada halted its test of similar net pens due to a marked decrease in water quality and increased rates of fish mortality, citing the “immature” nature of such new technology. Salmon farming is causing significant environmental impacts across the globe. Pollution, disease, and die-offs have resulted in serious damage in Scotland, Washington, and British Columbia. With a number of regions reconsidering ocean-based finfish farming altogether, Maine’s citizens have good reason to be concerned. Should something go wrong, the disproportionate impact felt by local populations–already vulnerable due to high levels of poverty–would be tremendous. With many households dependent on marine resources (e.g. fishing, recreation, and other maritime trades), algal blooms, fuel spills, and mass die-offs threaten to disrupt how people make their living on the bay.

“Small-scale, locally owned fisheries are not only economically important in Downeast Maine, they also create the traditional working waterfront lifestyle that permeates the coast.”

More than anything, however, the threat to the Downeast way of life seems to generate the strongest push back amongst communities surrounding Frenchman Bay. Small-scale, locally owned fisheries are not only economically important in Downeast Maine, they also create the traditional working waterfront lifestyle that permeates the coast. “The joy of being in Maine is that you can be self-employed and don’t have big companies coming in,” says lobsterman Zach Piper in the Portland Press Herald, “we own our own operations. When we start industrializing our fishing, we’re losing a sense of what Maine is about.”

My own family has strong ties to Frenchman Bay, and like many others, we are now confronting the potential changes associated with the industrialization of Maine’s waters. My mom grew up an hour from the coast in Bangor and now lives on Frenchman Bay in Sorrento, a tiny town in which my great-grandparents built a home now used by four generations of our family. Although I grew up primarily in Seattle, my roots are ultimately in Maine. Generations of my family have been enjoying life on Frenchman Bay since the early 1900s. However, a sense of upheaval permeates the air. During my most recent visit last summer, every other conversation centered on the American Aquafarms project and its potential to fundamentally alter this remote pocket of Downeast Maine.

“Ultimately, the fate of Frenchman Bay will be telling for the entire Maine coastline.”

The most striking aspect of the current battle for Frenchman Bay is the speed and intensity with which citizens have come together behind one cause. Even in the face of hundreds of millions of dollars of investment, local opposition only grows stronger, with many towns now passing short-term moratoriums on large-scale aquaculture projects. The state’s apparent support of the project stems primarily from the potential for jobs and economic stimulus. But what happens when everyone on the ground says they do not want those jobs, that they would rather maintain their existing way of life? Do the state and company back down? Ultimately, the fate of Frenchman Bay will be telling for the entire Maine coastline. With little existing regulation for water-based industrial scale aquaculture and cheap leasing fees, it is likely that more international investors will flock to develop their own farms should this project be successfully completed. Given the push-back already experienced by American Aquafarms, the road will not be easy. As of now, with the lease application still under review, the fight continues, and opponents show no signs of backing down.