The Destination City: The Future of Coastal Climate Migration

“I remember how much grief there is when a house is broken [by flooding], for so many things. I remember how this house that we struggled for was broken and gone. How can I stay, how can I survive?” – Participant 11 from my study, when asked what she remembers from her village.

In recent years, there has been a growing phenomenon of migration induced by climate change; projections estimate that, by 2050, anywhere from tens of millions to over a billion migrants will emerge. This mass displacement will affect every major continent, disproportionately impacting communities that have contributed least to the climate crisis. Who even counts as a climate migrant is a question to reckon with–a common story in the media is that of a rural Bangladeshi family whose home was swept by a flooding river, and they are forced to relocate. One contention with this image, though, is the fact that not all floods sweeping coastal Bangladesh are climate-induced; rather, many are due to poor infrastructure. Though a less graphic narrative, slow-onset disasters like sea level rise also produce migrants, as in the case of salinated waters which leave a fisherman without a steady livelihood, so they move to their nearest port city for shipwork. While the image may not be as graphic as a flood event, it is undoubtedly climate-induced. As climate migration unfolds, further concerns of planning and equity arise. Let’s begin.

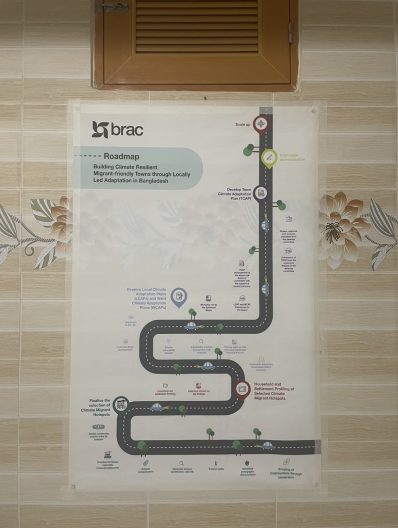

Because most climate migration is domestic and urban-bound, the burden of planning falls to a nation’s cities. Scholarship has historically been dominated by studies on the place of origin, but as migration accelerates, preparing destination cities has become increasingly pertinent. This gap encompasses both planning and research. It is worth noting that rural-urban migration is not new; in the case of Bangladesh, there is a long history of seasonal labor migration towards cities. It is well-documented that migrants in megacities like Dhaka are more likely to encounter slum housing and inadequate work conditions. As a result of this, researchers at the International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD) have begun developing a conceptual framework: “climate-resilient migrant-friendly cities and towns”. This framework includes features like proximity to origin, sufficient economic opportunity, and urban resilience as reasons why secondary/regional cities are more favorable alternatives for migrant resettlement relative to cities like Dhaka. One such example is the field site for my thesis research, the port city of Mongla, which has received scholarly and media attention in recent years. Mongla has been a destination for labor migration since the construction of its port; some participants in my study cite having come to Mongla as children when their fathers were laborers. The city has also made notable infrastructure improvements in recent years for cyclone and flood protections. However, it also faces severe freshwater scarcity and increasing housing pressure.

Mongla was chosen as a case study by ICCCAD, and I built on this research to investigate both what migrants characterize as struggles in their city as well as what their desired improvements were. It is worth noting that in my study I do not use the binary “climate migrant” and “labor migrant” in recognition of how entangled these categories have been; I rely instead on the terminology “flood-induced” and “non-flood-induced” migrants. My primary finding: migrants most often report struggling from water and resource scarcity, but they most often mention work opportunities as a desired improvement for their quality of life. A likely explanation is that work opportunity was overwhelmingly the primary pull factor that most migrants cited as the reason they came to Mongla. They also migrated from villages similarly suffering from salinated drinking water, so they came to Mongla expecting no different. Water is not the only service migrants lack that goes under-reported as a desired improvement. Migrants mentioned healthcare, safe housing, and infrastructure as needing improvement in other parts of the interview, but not when directly asked. This reveals the nuance of approaching bottom-up research: had the primary method been a survey, these obscured burdens may not have been captured. Moreso, the interviews reveal Mongla’s limitations as a model destination city from the perspective of migrants. As the “climate-resilient migrant-friendly cities and towns” framework continues to develop, it is critical that researchers and planners practice methods that not only engage the community, but are also structured in a manner that allows the indirectly said but still pertinent testimonies to be captured.

The future of climate migration is not only in the development of the destination city, but also in planned relocation, or the resettling of a community to a less climate-vulnerable area. According to Bangladesh’s most recent National Adaptation Plan, the government does not have plans to institute this adaptation strategy until after 2041, although there have been successful cases in the U.S. A notable example is the community of Isle de Jean Charles, who in 2016 received the first U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development climate-resilience grant for planned resettlement. Alaska has also planned several planned relocations, especially for indigenous communities. One such example is the town of Newton, which has been planning its relocation for decades. There are also U.S. “climate havens” that ring similar to Mongla in their history of accepting migrants fleeing climate impacts, such as Nashua.

Bangladesh and the U.S. may have significantly different manifestations of climate change on their landscapes, but migration is a shared phenomenon. To accommodate this shifting population, both countries will need to prepare their cities for the migrant influx. As the case of Mongla shows, the needs of migrants are sometimes articulated between the lines, so to ensure a high quality of life, researchers and planners will need to engage with the community thoughtfully and critically to produce a resilient infrastructure aligned with the principles of environmental justice. Being mindful of nuance is particularly relevant; I separated the categories of flood-induced and non-flood induced migrants to align with research that shows how distinct resource availability may be for those being displaced by climatic factors. A case in Bangladesh is the Khurushkul Special Ashrayan Project, which is a government housing project created specifically for those displaced by climate change events. Understanding the varied circumstances with which migrants are arriving, climate-related or otherwise, can allow the government to allocate provisions in an equitable manner. I will end this article with the words of a flood-induced migrant from my study, as he responded to the question, “Why did you come to Mongla?”

“I will tell you that we had no refuge after the house was destroyed. There is no other situation to seek refuge. So we came to this Mongla port. My father used to work in Mongla Port before. He used to work at the ships here. So after everything was broken, my father came here with everything left. Houses had been washed away. The houses are totally gone. Our ancestral home is gone. All dissolved in the river, carried away by the river. All went down with the river.” – Participant 16