Sylvia Plath’s Longing for Her Seaside Childhood: A Literary Analysis

Content warning: This article contains brief references to suicide.

American poet and author Sylvia Plath is widely regarded as a leading example of the confessional poetry movement. Confessional poets often ground their work in autobiographical events and connect these to subjects considered private or taboo for the period: family dynamics, trauma, mental illness, and suicide. My high school IB English Language and Literature teacher introduced me to Plath’s work and I immediately fell in love with her writing. Our class critically read selected poems for weeks in preparation for an analysis assessment. But the homework went beyond earning a grade for me– the poems sparked a lifelong love of poetry. I bought The Collected Poems and read it cover to cover in the spring of 2015, carrying my copy with me everywhere and underlining my favorite passages in black pen.

For me, Plath’s work carried great emotional depth and her mastery of the craft showed through unique turns of phrase that stayed with me long after reading the stanzas.

Since Plath’s work is central to the confessional poetry movement, many argue that she uses natural imagery solely to portray her complex inner thoughts and emotions. While I am not a literary scholar, based on my readings of The Collected Poems, The Bell Jar, Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom, and some of Plath’s short stories, I believe that her love for nature and the ocean stems from childhood and carries into her adult life.

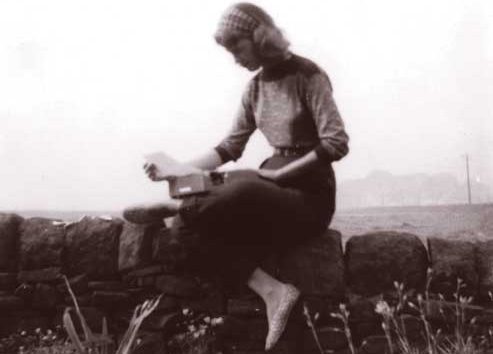

A Seaside Upbringing

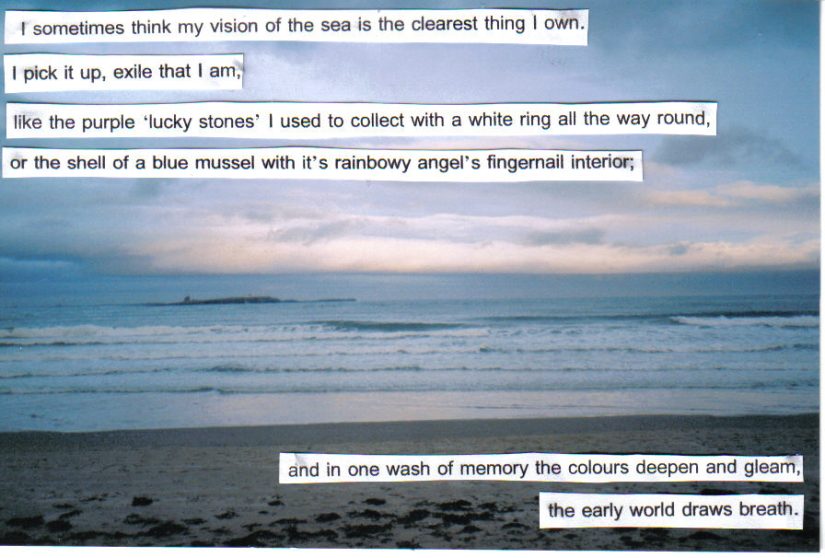

Born in Boston in 1932 and raised in the small seaside town of Winthrop, Massachusetts, the Atlantic Ocean influenced Sylvia Plath during her formative years. She writes in the autobiographical short story “Ocean 1212-W”, “My childhood landscape was not land but the end of the land—the cold, salt, running hills of the Atlantic. I sometimes think my vision of the sea is the clearest thing I own.” “Ocean 1212-W” not only records Plath’s early childhood fascination with the ocean but also reflects upon her poetic heritage—the experience of growing up in the seaside town that influenced her future prose.

“Ocean 1212-W” recounts the origin of Plath’s identity through both her connection to the ocean and her love of words and poetry. Plath describes her time walking along the beach, noting the nature around her. The colorful world of the seaside reflects her in brown and green sea glass and bits of broken china she finds while beachcombing. Leaning into fantasy elements as a young girl, she believes in mermaids perched on rocks and the legend of Davy Jones. Similar to Plath, I also have a deep connection to the location of my earliest seaside memories of playing along the rocky shore of Marrowstone Island on family trips.

“Did my childhood seascape, then, lend me my love of change and wildness?” – Sylvia Plath

Unfortunately, Plath’s idyllic upbringing could not last. Her father’s illness and subsequent death devastated Plath and marked a shift in her young life. Plath reflects, “And this is how it stiffens, my vision of that seaside childhood. My father died, and we moved inland. Whereon those nine first years of my life sealed themselves off like a ship in a bottle—beautiful, inaccessible, obsolete, a fine, white flying myth.” Plath intertwines memories of joy and discovery with feelings of loss for a period of her life that she can no longer physically return to. The only way she can revisit this time is through her poetry and prose, which leads Plath to write in vivid detail about her seaside childhood. Even though it has been over 20 years since my last visit to Marrowstone Island, Plath’s reflection on her childhood memories reminds me of the carefree joy I felt while spending an afternoon on the beach.

Environmental Influence

Rachel Carson brought the nascent environmental movement into the mainstream with her 1962 book Silent Spring, which exposed the effects of industrial chemicals on animals, plants, and humans. The book is often referred to as the spark that ignited the modern environmental movement of the 20th century. While it is unclear if Plath read Silent Spring before her suicide in February 1963, letters suggest she was familiar with Carson’s earlier works and interested in environmentalism. In a letter to her mother on July 5th, 1958, Plath wrote: “I am reading… the delightful book The Sea Around Us, by Rachel Carson; Ted’s reading her Under the Sea Wind, which he says is also fine. Do read these if you haven’t already: they are poetically written, but magnificently informative. I am going back to the ocean as my poetic heritage and hope to revisit all the places I remember in Winthrop with Ted this summer.”

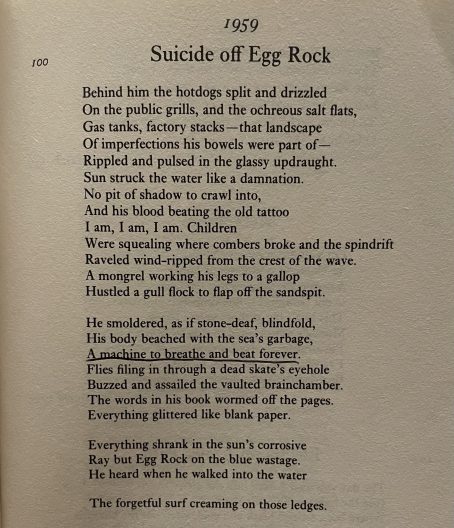

Plath wrote a series of poems relating to the seaside and ocean in the months following the trip including Green Rock, Winthrop Bay, Point Shirley, Suicide off Egg Rock, and Magnolia Shoals. Plath relies on observational language in many of these poems, describing the beaches impersonally through what the speaker experiences from their senses while walking along the shore. She explores themes of isolation, loss, and disillusionment the speaker feels when returning to the seaside as an adult. These intense emotions reflect Plath’s desire to return to a peaceful seaside childhood that no longer exists. I underlined “A machine to breathe and beat forever” during my first read-through of Suicide off Egg Rock in 2015. The line represents the speaker’s feelings of numbness mirroring the ceaseless crashing of waves on the beach. I am not sure what originally drew me to that particular line, but upon rereading it I love how it connects human emotions to the natural world.

Crossing the Atlantic

Shortly after writing those poems, Sylvia Plath moved with her husband, British poet Ted Hughes, to England in December 1959. While she lived in Cambridge as a Fulbright scholar in 1956, this marked Plath’s permanent departure from her New England home. When Plath became nostalgic for her oceanside childhood, Hughes would bring her to the nearest English shoreline. “‘There,’ I’ll be told, ‘there it is.’ It was as if the sea were a great oyster on a plate that could be served up, tasting just the same, at any restaurant the world over. I get out of the car, I stretch my legs, I sniff. The sea. But that is not it, that is not it at all”. Since Plath’s homesickness was for her childhood as opposed to simply seeing the ocean, visiting England’s shores did not satisfy her longing for a time and place she could no longer visit. I have experienced feelings similar to Plath’s when visiting other rocky Salish Sea coastlines that at first resemble the Marrowstone Island beach of my youth. No matter how comparable the shores of other islands are, it is the childhood memories of catching shore crabs and climbing on the smooth branches of Pacific madrones that set that particular coastline apart from all others.

In the years following her move across the Atlantic, Plath wrote “Ocean 1212-W” and several more poems that contain ocean imagery including Blackberrying, Finisterre, and Contusion. In these poems, she uses the shoreline as a metaphor for the inevitable end of what is safe or known which plunges into the vast emptiness of the ocean. This theme is clearest in Finisterre, written about the Cape in Spain once thought to be the end of the world. These poems no longer reference the colorful shores of her childhood memories but instead represent the sea as bleak and desolate shown through her choice of dull color imagery throughout.

Flipping through the pages of The Collected Poems ten years after reading it for the first time, I reread some of my favorite poems marked by a black star next to the title. Among my favorites were Blackberrying and Finisterre written just days apart in September 1961. Even with Plath’s use of dark color imagery in these later poems, her word choice remains strikingly descriptive and I can almost taste the salt of the sea air as I read. The evocative poems and prose with ocean imagery throughout Sylvia Plath’s body of work cause me to think back to my own early coastal childhood memories. I recall the joyful exuberance of discovering the natural world for the first time which continues to inspire my work to protect these shorelines today.

The following sources were used that may be behind a paywall, please contact the Currents Editor-in-Chief for access.

[1] Brain, Tracy. (2001). The other Sylvia Plath. In The Other Sylvia Plath (Longman Studies In Twentieth-Century Literature). Longman.

[2] Knickerbocker, S. (2009). “Bodied Forth in Words”: Sylvia Plath’s Ecopoetics. College Literature, 36(3), 1–27.

[3] Lowe, P. J. (2007). “Full Fathom Five”: The Dead Father in Sylvia Plath’s Seascapes. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 49(1), 21–44.