Reviving Coal Mining in King County

By Colin Bowser

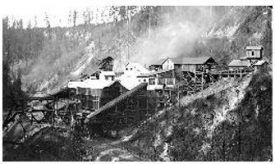

While modern-day industry in Seattle has become synonymous with technology companies, few people realize that the regional economy was once far more coal-black than environmentally-green. With industries like aerospace, timber, and shipping dominating the Puget Sound area of today, it is often not remembered that Seattle and its surrounding counties grew and flourished on the most notoriously polluting hydrocarbon: coal. Even more jarring is the possibility that coal mining could soon return to Puget Sound if federal officials approve a local company’s new proposal.

In the second half of the 19th century the first transcontinental railroads opened the West to rapid settlement. This generated a large demand for coal to fuel locomotives and the burgeoning infrastructure of the growing towns. As the California gold rush of the 1850s and resulting expansion surged, California’s demand for coal as a heating and industrial fuel rapidly grew. This growth was in tandem with the Puget Sound region’s smaller, but increasing demand.

Explorers and early pioneers found coal seams at several locations around Puget Sound soon after white settlers arrived in the 1850s. One such mine on the eastern shore of Lake Washington used a coal shipping point on the present-day location of the University of Washington crew teams’ boathouse to ferry coal to waiting steam ships moored at Elliot Bay.

Dozens of other coal mines opened as the growing population of settlers and industries produced increasing energy needs. This local market combined with the much larger energy market of San Francisco to the South created a potent market force for coal. By the 1880s, Washington coal was the chief source of fuel for San Francisco and a profitable business for industrialists, but change was already materializing that would make this boom short-lived. In the ensuing decades, Washington’s coal mining industry sagged under the weight of union labor unrest and market competition from other energy sources like petroleum and hydroelectric power.

By the 1990s, only one coal mine – the John Henry mine – remained in operation in Washington, outside the aptly-named town of Black Diamond in southeast King County. By then, coal could be more economically mined and transported from huge mines in Wyoming and Montana to some of the last remaining local industries in western Washington still dependent on coal. These were the TransAlta Company’s enormous coal-powered electric power plant in Centralia (about 15 miles south of Olympia) and several cement plants around Seattle and Vancouver, British Columbia.

But just as the (coal) dust settled on Washington’s old energy mining industry 18 years ago, a new proposal may soon allow Pacific Coast Coal Company of Black Diamond, WA to reopen its long-closed mine. The idea of reopening the John Henry mine has apparently been simmering for the last 15 years and the idea codified again this year with a fresh proposal by Pacific Coast Coal and an initial favorable determination by the U.S Department of the Interior this past September. The company proposes to reopen the surface (or “open pit”) mine and extract 84,000 tons of coal per year for six years, after which the mine would close again. The coal would be trucked to several industrial locations around the region, including one right in Seattle’s backyard – a large cement production plant owned by the Ashgrove Cement Company in South Seattle. In spite of the largely-green societal views of Puget Sound and its environmentally-conscious public, the Department of the Interior determined in a September report that resuming surface mining operations at the John Henry mine for six years would “not have significant impact on the quality of the human environment.” For this reason, the office will not require a new environmental impact statement.

Even with the vast amount of more or less renewable hydroelectric energy the state derives from its dams, the TransAlta power plant, using both coal and natural gas to power its two boilers, generates considerable electricity to an ever-growing population hungry for power. The plant would be a willing customer of the John Henry mine. It remains to be seen how the state’s power grid will operate when the coal portion of the coal & natural gas plant shuts down as scheduled in 2020. Until then, the Centralia plant receives nine 110-car trainloads of coal per week from Wyoming and Montana.

After the Department of the Interior’s favorable determination on the John Henry surface mine, a period of public comment is now open and the people have a chance to offer their views. Local government in King County and government at the state level in Olympia have vowed to fight the Department’s determination and will try to keep the mine closed. Mining and burning the coal in the current Pacific Coast Coal proposal would annually release the amount of CO2 equivalent to operating 51,000 new cars around Puget Sound.

The Department of the Interior may strongly assert its voice in the issue, in part because Washington is one of only two states who delegate state mining regulation to the federal government. Whatever the outcome, cost-effective, readily-available fuel and the benefits it provides will lie in tense balance with Puget Sound’s delicate natural environment.