Reflections on the June 2021 Heat Wave

From June 26-28, 2021, the Pacific Northwest experienced an unprecedented heat wave. Despite news coverage moving onto other immediate concerns before hashing out concrete policy responses, it felt like a pivotal moment in climate policy as it was happening. I am worried that the world may be moving on without committing to appropriate action. In hopes of contributing to a call for impactful policy response, I offer my personal account of the heat wave and my understanding of the broader social context.

Pre-heat wave, Seattle was the least air conditioned major city in the United States. Historically most summers didn’t seem hot enough to justify it, so more than half of homes went without. Most businesses have it, though, so I’ve generally been fortunate to work in temperature-controlled buildings.

On June 26, I was working the Saturday brunch shift waiting tables. Our AC wasn’t really working. The guests kept coming anyway, determined to enjoy their meals out, after over a year of COVID restrictions. Between orders, servers flocked to the break room. We plunged our hands into a tub of ice water and guzzled down agua fresca the line cooks shared with us. A couple of my coworkers visibly struggled with the heat. Outside the temperature climbed to 102 degrees Fahrenheit. It was even hotter in the kitchen. When I got home that night our apartment was sweltering, despite my partner’s care to close the windows before the heat spiked and to arrange the fans just so. The concrete building retained heat, making the night only marginally more comfortable than the day and indoors, at times, apparently warmer than outdoors.

Sunday was hotter, reaching 104. It felt much worse than the day before, perhaps partially from the cumulative effect of being unable to recuperate from the prolonged heat. That afternoon the restaurant closed early. Walking home through downtown Seattle, I woozily passed door after door with signs indicating that other businesses had been forced to do the same. When I got home that day, my partner and I desperately tried to cool our two cats, picking up tips from my SMEA colleagues and veterinary websites.

The third day of the heat wave was the hottest at 108 degrees. My work was closed on Mondays and my partner’s telework had given employees affected by the heat wave the day off. We spent the day in a stupor until the temperature finally fell, desperately trying to convince the cats to play with ice cubes and dabbing them with a damp washcloth like my classmates had taught us.

During those three days, the government provided public cooling stations. They were a much-needed service, but too few and far between to be widely accessible to everyone in need. Some local businesses stepped up too, but again, this was not scalable to the population of a major city. It just wasn’t something our infrastructure was set up for. Social media was inundated with requests to bring water and ice to unhoused people. Ice was sold out absolutely everywhere. In my neighborhood we timidly left bottled water in shaded areas outside folks’ tents and hoped they were somehow alright in there.

Ultimately at least 112 people were killed as a direct result of the heat wave in Washington state, with at least 116 additional deaths in Oregon and an estimated 570 in British Columbia. The U.S. figures are likely underestimates, as heat related deaths often take the form of cardiovascular failure or other causes of mortality, which generally take months to attribute accurately. It does not, of course, address lost years and quality of life as a long-term result of extreme heat exposure. All of these losses were experienced disproportionately by human beings already bearing the brunt of societal inequities: BIPOC communities, vulnerable workers, the poor, the unhoused.

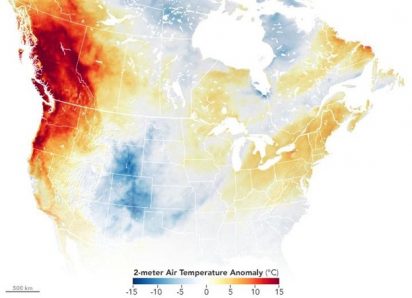

The heat wave was the result of what was colloquially referred to as a heat dome, a phenomenon in which hot air is trapped over an area and stagnates instead of circulating away. Heat domes are one of the climate anomalies expected to increase in frequency and severity with the progression of climate change. Experts have already determined that the Pacific Northwest could not have experienced such an extreme heat dome without effects of climate change. In other words, the heat-related deaths were the combined result of systemic inequity and climate change.

All that only addresses the human dimension of loss. In Canada alone, over a billion marine animal deaths were attributed to the heat wave, which is both harrowing in its own right and devastating to the ecosystem. Yet there didn’t seem to be enough political capital left after a year of pandemic to treat the heat wave with the gravity and urgency it should command. As University of Washington professors Nives Dolsak and Aseem Prakash note, even the dire new IPCC report was eclipsed in the news cycle without driving concrete policy change. While this is understandable, given the seemingly more immediate threat posed by the Delta variant and widespread news fatigue after over a year of disappointment and disillusionment, it is also unacceptable.

We must not allow policymakers to gloss over the gravity of our shared experience by continuing to delay climate action. Whether policy catches up in time to mitigate future disasters, the heat wave was a pivotal moment. The news has started acknowledging that climate change is already happening, rather than relegated to a hypothetical future. The way I think has changed too. Until this year, I couldn’t single out clear examples of climate change I directly experienced. It was happening somewhere else, or too nebulous to be sure of or hadn’t really started to pick up yet. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, nearly everyone in my life was caught in a horrific heat wave that would not have occurred without climate change. Most were lucky insofar as we only experienced discomfort and inconvenience, but it killed hundreds of people and over a billion marine creatures while causing lasting damage to the environment.

As Washington governor Jay Inslee pointed out, air conditioning alone isn’t a tenable solution. AC contributes heavily to the emissions at the root of the problem and does not address the full scope of hazards increasing with climate change. More of us will need to get AC to stay safe, but AC needs to become more efficient and we need to pair it with improvements in building design. And we need to demand policy changes that reflect the danger we now live with in the era of climate crisis. Passage of time without meaningful policy change risks desensitizing us to escalating tragedy by establishing inaction as an acceptable status quo. This can’t become the new normal, but if we don’t acknowledge climate change as a deadly emergency with both causes and solutions, it very quickly will become so. Is it finally time for the New Green Deal? If not, what policy alternatives do you prefer? It is time to demand concrete action.