Indigenous Youth Leadership: Resistance in the Age of Pipelines

In the age of social media, it has become easier than ever to stay up to date with social movements and protests both domestically and internationally. The internet has created a new way for groups to tell their stories and provide information without a third party. The power of this information sharing can be seen throughout modern anti-pipeline movements around North America such as #IdleNoMore, #NoDAPL, and #StopLine3. Apps like Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter have allowed frontline protestors and activists, who are primarily Indigenous land and water defenders, to share what is happening on the ground. Blogs and websites enable those within these movements to provide information beyond the immediate community to a greater audience.

Of all the voices calling attention to violence against the land, special attention should be paid to the young people within these anti-pipeline movements. Indigenous youth have spearheaded the anti-pipeline movement through social media and have been leading the way to a land-honoring future. This article focuses on the impact of pipelines on Native land and communities, what Indigenous youth have been doing to combat them, and the significance of these movements.

What is the problem with pipelines?

Oil-carrying pipelines have been around since the 1860s, and have always faced opposition. In the US alone, over 2.5 million miles of pipelines deliver trillions of cubic feet of natural gas and billions of tons of liquid petroleum products each year. These pipelines ostensibly serve to connect refineries, oil production or import areas, and market terminals. However, they also present myriad social and environmental problems.

To start, the use of petroleum products carried by pipelines adds greenhouse gasses to our atmosphere, thereby perpetuating climate change and its associated risks. These local and large-scale impacts — which include drought, flooding, heat waves, more frequent and stronger storms, higher sea levels, and the loss of Arctic ice — are irreversible on the timescale of people alive today and will continue to worsen in future years. Western society is heavily dependent on fossil fuels: from the vehicles we drive to the power plants sustaining our lifestyles, burning fossil fuels can be found in the tiniest corners of our lives and all contribute to these problems.

The construction of pipelines to carry fossil fuels also has a massive impact on the land. Laying the pipe necessitates excavating a trench to match the length of the proposed pipeline and/or constructing an above-ground channel. Both of these must circumnavigate or cross existing roads, highways, streams, rivers and wetlands, abandoned mines, and populated areas. Constructing and using pipelines can destroy the beauty and function of land, watersheds, and waterways, destroying habitats and endangering many species. In this destruction, they are an act of modern day colonization. Pipeline companies also often evoke eminent domain, which can allow them to seize private land against the landowner’s will if they can describe the pipeline as providing a public benefit. This practice essentially makes it legal for such projects to steal and damage land.

Additionally, operational pipelines always present a threat of spills. If a pipeline is improperly assembled, becomes too hot or too cold, or is simply too old, it can burst or leak its contents into the surrounding area. There were over 3,000 oil spills in the US between 2012 and 2020, releasing over 100,000 barrels of oil into the nearby environment. Oil is deeply toxic, and can cause physical and biochemical harm to living organisms depending on their level of exposure. For human communities, this can mean chemical pneumonia, headache and dizziness, drowsiness, loss of coordination, nausea, labored breathing, irregular heartbeats, convulsions, and comas; for pregnant people it can also result in birth defects and miscarriage. Air pollution from fossil fuels is responsible for more than 13% of deaths in people aged 14 and older in the U.S.

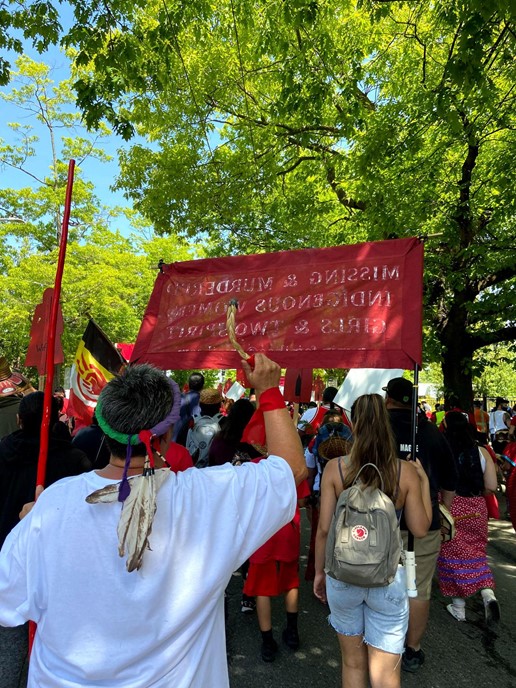

Finally, pipelines present significant social problems. They bring extensive external work into Indigenous communities. These workers, many of whom are non-Native, set up residential “man camps” while building a pipeline. Such man camps are associated with exacerbated rates of sexual violence, sex trafficking, and overall harm. This epidemic sparked the #MMIW movement, or Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, whose goal is to raise awareness, spread information, and eradicate the problem.

Thus, Native land and water defenders have been willing to risk their bodies, freedom, and lives to fight the injustice and ongoing violence that pipelines represent.

All of these aspects of big oil have inherent implications for Indigenous peoples. Black, Brown, Indigenous and low-income communities are disproportionately impacted by fossil fuel infrastructure since companies intentionally target these neighborhoods for development, which in turn leads to higher rates of pollution. Because these communities often live in treeless, concrete neighborhoods that are more susceptible to extreme weather events, they bear the brunt of climate change impacts as well. Loud noises, human movement, and vehicle traffic from oil operations can also severely fragment habitats for many species and disrupt animals’ communication, breeding, and nesting. Many Indigenous people have ties (sometimes economic, cultural, intergenerational, and/or spiritual in nature) to the land, water, and non-human kin in their communities, meaning that pipelines not only perpetuate climate change, but harm Indigenous ways of being. Thus, Native land and water defenders have been willing to risk their bodies, freedom, and lives to fight the injustice and ongoing violence that pipelines represent.

What are Indigenous youth doing to combat pipelines?

Young Indigenous activists have been defending land and water rights on two fronts — physically and through social media.

Social media has been integral in raising awareness about pipelines, and this is most clearly seen through the three most recent pipeline protest movements of #IdleNoMore, #NoDAPL, and #StopLine3. Arguably starting in 2012 with #IdleNoMore, Indigenous land and water defender movements began to gain serious traction in the mainstream media. The Treaty People who sparked #IdleNoMore sought to protest the undoing of environmental protection laws in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, Canada. Later in 2016, the #NoDAPL movement began in Standing Rock, North Dakota to protest a pipeline being constructed about one mile from the Sioux Reservation despite having no prior consultation with the tribe. After fighting the pipeline’s construction, the community began to protest on site and on social media. A Facebook post asking for helped started #NoDAPL, causing thousands of people, Indigenous and not, to travel to Standing Rock in solidarity. The most recent viral protest was #StopLine3, the movement protesting the Enbridge pipeline carrying crude oil from Alberta, Canada to Superior, Wisconsin. With these monumental movements acting as a springboard, the #StopLine3 movement gained momentum fast. Protestors raised a variety of concerns — the pipeline construction through Anishinaabe territory threatens to destroy swaths of essential watershed habitat, violates Indigenous treaties, and participates in the crude oil industry that contributes more to climate change than anything else. With almost fifty thousand and fifty million posts using the hashtag on Instagram and TikTok respectively, young Indigenous activists created solidarity online like never before.

Indigenous youth activists have organized resistance to pipeline projects outside of social media, too. Teens and young adults from Standing Rock and the neighboring Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation organized a 2,000-mile relay run to D.C. last spring to deliver a petition (signed by over 400,000 people) calling on the Biden administration to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline and Line 3. After delivering the petition to the Army Corps of Engineers headquarters, the group of young protesters then marched to the White House where they staged acts of resistance. Joseph White Eyes and Lawrence Lind, both of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, sat on platforms suspended high above the ground while others U-locked their necks to the base of the platforms to prevent them from being moved. The group organized a “die-in” to represent the lives lost due to environmental destruction from pipelines. They touted a 300-foot long black snake puppet during their protest, which represents pipelines as terrifying entities threatening life on Earth, and used the prop to shut down traffic and garner attention. They were partially heard; on his first day in office, President Biden overturned the permit for the Keystone XL pipeline (however the Dakota Access and Line 3 pipelines were not addressed).

In Vancouver, another fight is underway. The proposed Trans Mountain pipeline would carry crude oil from the tar sands of Alberta to the British Columbian coast. Tar sand crude oil is widely considered the world’s dirtiest oil. Last February, 20 Indigenous youth from the xʷməθkwəy̓əm, Skwxwú7mesh, Səl̓ílwətaɬ (Musqueam, Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh) and other First Nations occupied the lobby of Chubb Insurance Company, one of 11 insurers backing the pipeline project. Many of the protesters wore red dresses in honor of #MMIW and hoisted a banner reading, “Stop Insuring Genocide,” referring to the environmental destruction associated with the project as well as the violence against Indigenous women and girls. The same group then occupied the lobby of Liberty Mutual Group, which in addition to insuring the Trans Mountain project also backs the Alberta oil sands and the now defunct Keystone XL pipeline.

Yet, this article cannot capture the true scope of Indigenous youth activism standing up against the threat of big oil and pipeline construction. Young figures have taken a stand in the center of the problem as well as the adjacent threats, such as fighting for Land Back, food and water sovereignty, and culture reclamation. Young figures such as Autumn Peltier, Anishinaabe-kwe, and has been a prominent figure in fighting for Indigenous water rights since she was 12 years old. Model and 19-year-old Indigenous advocate Quannah Chasinghorse, Hän Gwich’in and Sičangu/Oglala Lakota, has been a major figure in the world of fashion and activism with her work in land-protection. These young people, among others like Jasilyn Charger (Cheyenne River Sioux cofounder of 7th Defender’s project and currently facing imprisonment for resisting Keystone XL pipeline in her homeland), Cadee Peltier (Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewas), Maya Monroe Runnels-Black Fox (Co-chair of the Standing Rock Youth Council), and many more have been integral to the Indigenous land and water rights movement.

What is the significance of these youth-led movements?

Thanks to generations of Indigenous activism, many other people are beginning to open their eyes to the fact that fossil fuels are a non-renewable and destructive resource that we will not be able to rely upon in the future. A shift away from fossil fuels is imminent, but the phase out of those resources is not happening at a rate to prevent current and worsening environmental, health, and spiritual damage to Native people and lands. Indigenous water and land defenders are the oft-unsung heroes in the fight against unsustainable, damaging fossil fuel infrastructure, and young people are at the center of this battle taking up the mantle in a new and challenging era.

The widespread involvement of youth from different Indigenous communities has also created a network of solidarity in this battle: the ultimate goal is to end all pipelines, not just the ones that affect their immediate community. These youth-led movements demonstrate a shared sense of urgency to act on behalf of the fate of the world they will inherit.

An important distinction in this discussion is that Indigenous youth are not only involved as activists in anti-pipeline work: they are leaders of these movements. In leveraging technology — especially social media — to organize, these young land and water defenders have been able to rally multiple generations of activists in the fight against pipelines. By putting their time and bodies on the line to take on massive corporations, these Indigenous youths are attempting to hold older generations accountable for their actions (or lack thereof) when it comes to fuel infrastructure and environmental degradation. The widespread involvement of youth from different Indigenous communities has also created a network of solidarity in this battle: the ultimate goal is to end all pipelines, not just the ones that affect their immediate community. These youth-led movements demonstrate a shared sense of urgency to act on behalf of the fate of the world they will inherit.