From One Washington to Another: What the Infrastructure Bill will do for Washington State’s Working Waterfronts

The Thursday of Memorial Day weekend 2013. A caravan of college kids, myself included, were traveling from Bellingham to George, Washington for the now dearly departed Sasquatch Music Festival. We passed over the I-5 Skagit River bridge on our way south. Not long after, as I recall, someone in our car got a call. The back half of the caravan didn’t make it because part of the highway had collapsed. Our friends got redirected and made it to the party several hours later. Two other cars had fallen into the river as the bridge crumbled, taking three passengers down with them. All three were rescued and there were no fatalities.

I frequently drive from Seattle to Bellingham, and I think about this story every time I cross that bridge. I used to drive over triangulated steel grate. Now it’s completely concrete.

The collapse was caused by a southbound semi-trailer truck from Canada hauling an oversize load to Vancouver, Washington. It directly damaged sway struts, which indirectly compromised the compression chords in the overhead steel trusswork frame on the northernmost span of the bridge. Evaluated as safe and in good condition despite being 58 years old, the bridge was not listed as structurally deficient at the time of its collapse. It was not a candidate for any significant upgrades or replacement and was well-maintained. It had, however, been classified as functionally obsolete, because it did not meet current design standards for lane widths and vertical clearance.

Washington has 416 bridges and more than 5,400 miles of highway that are in poor condition. According to this Report Card released on April 11th, 2021, our state’s infrastructure received a C grade.

In November of last year, Congress passed President Biden’s $1.2 trillion bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). Enjoying widespread approval, 6 in 10 Republican voters say they favor the new package, perhaps because of the estimated 660,000 jobs that could result by 2025. Washington will see nearly $8.6B in dedicated funds and billions more in potential grants. But, policy experts caution against expecting an immediate impact from the infrastructure measure. With long-needed funds for upgrading the nation’s roads, bridges, pipes, ports, broadband and other public works on the way, I want to know what that means for Washington. In particular, I want to look at what that means for our waterfront and ports.

Why the interest in ports? During my first job after undergrad, at the Working Waterfront Coalition of Whatcom County (say that ten times fast), I learned how extensive a port’s reach can be and what a profound development muscle ports are. Not all ports are located on waterways. Instead, ports are more broadly defined by their primary function of facilitating economic growth. Have you ever caught a flight out of Sea-Tac International Airport? That is a branch of the Port of Seattle, as are some of the railways. With more than 90% of the world’s trade carried on ships and planes, port infrastructure is fundamental to the national and regional economy and quality of life — especially in one of the most trade-reliant states in the nation. U.S. ports enable the development of 26% of the national economic output and support 30 million jobs.

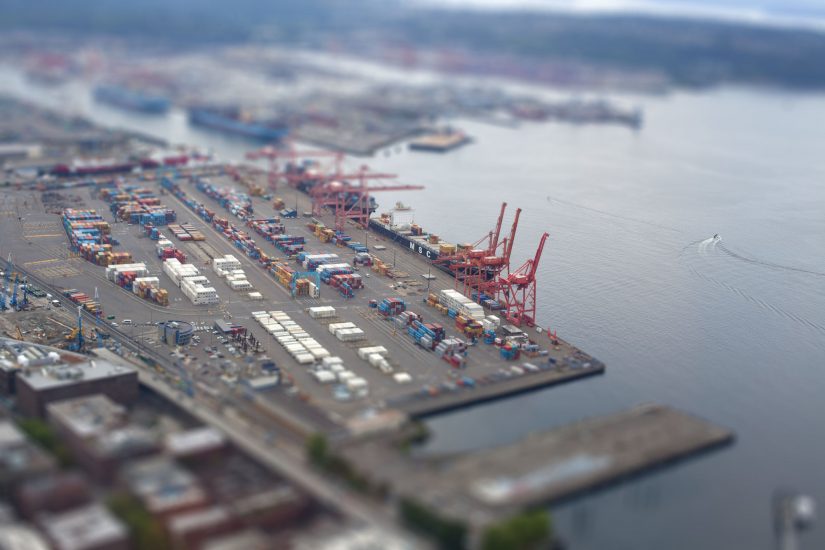

Only four U.S. ports are among the top 50 busiest globally, and no U.S. port is in the top 10. Ports in the Pacific Northwest offer the shortest travel distance for goods moving between Asia and North American markets. In Washington, there are 74 ports located in 33 of the 39 counties, with only 11 deep-draft ports (meaning water depth greater than 35 feet), seven of which are in Puget Sound. Depth limitations and other obstacles like bridges restrict the ability of many U.S ports to receive larger, new Panamax vessels resulting in less national commerce. Open to commercial traffic on June 26th, 2016, the Panama Canal Expansion Project (also called the Third Set of Locks Project) doubled the capacity of the Panama Canal. New lanes of traffic were added, and the width and depth were increased, allowing for larger ships and a larger number of vessels to pass. The new boats, called Post-Panamax, are about one and a half times the previous Panamax size and can carry over twice as much cargo.

Ports and Waterways

The IIJA is the single largest federal investment for American ports in U.S. history. Infused with $17B, ports will literally be reshaped in the years ahead as dredging projects move forward to allow bigger boats to enter waterways and more ships to dock at once. Most of the funding will be directed through the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the Department of Transportation (DOT).

USACE of Washington will receive $68.82M for projects ready to break ground. Repairs are lined up for work on the Grey’s Harbor North Jetty at Ocean Shores, the small-locks machinery and control system at the Hiram M. Chittenden in Seattle, the Quillayute River sea dike in La Push, and Port Angeles’ Ediz Hook revetment.

The funding dispersed to the DOT will be managed primarily through the new Port Infrastructure Development Program (PIDP). A strong supporter of the PIDP and the Chair of the Senate Commerce Committee, Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) lobbied hard for a record $2.25B for the program to be included in the IIJA. Washington State can expect around $23.79M to distribute around the state as grants.

The Port of Tacoma has already been awarded $15.7M for an off-dock container support facility. The facility will create an additional 24.5 acres worth of dock space to help ease congestion. Delays due to congestion have resulted in (among other things) shortages of public school cafeteria food. Ships carrying perishables have been held up, sometimes for weeks, causing produce to rot in their containers, resulting in huge losses and reduced food supply. Sen. Cantwell says trade and port infrastructure is key to our state’s competitiveness, “Because if someone doesn’t think their product can move quickly through our ports, they’ll choose other places.”

Working with the Federal Maritime Commission to publish a request for information on standardized data exchange requirements in the transportation supply chain, the DOT will publish a playbook for States on using grant and loan programs to support goods movement to help alleviate freight bottlenecks.

The Port of Ilwaco, at the entrance to the Columbia River, will receive $2.44M in PIDP spending. The grant will be allotted for critical improvements to its commercial fishing wharf, protecting the fishing community and its facilities from the challenges of climate change.

Similarly, threatened by climate change, the United States Coast Guard’s (USCG) shore facilities will receive $429M in IIJA funds for new construction, in addition to housing, family support and childcare for service members. How much will be reserved for Washington Coasties is not specified.

Washington State has 13 land border crossings along the 427 miles it shares with British Columbia. The most popular of these crossings are the four that primarily serve the Vancouver-Seattle area: the Peace Arch, the Pacific Highway from Blaine to Surrey, farther east Lynden to Aldergrove, and Sumas to Huntingdon crossings. These ports of entry handle more than 30,000 vehicles that cross the Washington border daily and can have wait times as long as 3-4 hours during peak traffic. These four land ports of entry will be upgraded through IIJA via the General Service Administration (GSA) and Customs and Border Patrol (CBP). The Pacific Highway Land Port of Entry in Blaine is slated to receive more than $20M to increase the number of inspection lanes.

The two largest ports – the ports of Seattle and Tacoma – together make up the second largest load center in the nation. The Northwest Seaport Alliance (“Alliance”) of the Port of Seattle, Tacoma and Vancouver, BC is in the top 5 largest container gateways in North America. The Alliance handled approximately $66 billion of waterborne trade with 189 trading partners globally in 2020. Marine cargo operations at Alliance facilities support over 58,000 jobs and drive over $12.4 billion in economic activity in Washington state.

Over the next five years, with an investment of $400M, national ports are reducing emissions from trucks on their properties. The Alliance has already reduced emissions and met performance targets to improve air quality through the Northwest Ports Clean Air Strategy. With financing from the IIJA, the Washington Department of Ecology has awarded $91M to the Northwest Seaport Alliance for initiatives like cracking down on idling and switching to electric vehicles. The Port of Seattle Commission voted to accelerate its emission reduction efforts by ten years to be net zero or better by 2040. The Port also committed to accelerating and expanding its goal for emissions from industries operating at its facilities to be carbon neutral or better by 2050.

Ferries

The Marine Highway (DOT) is a program to expand the network of navigable waterways, from rivers to the Great Lakes, down the coasts and includes open-ocean routes. Route M-5 connects Washington to Oregon and California. Over five years, the IIJA will pay out $25M to improve Route M-5. This year $12.6M has been awarded to nine (out of 26) marine highway routes, one of which is M-5. How much exactly Washington can expect for M-5 of that $12.6M is unknown. Competitive grant applications are still open for the program.

Receiving $1.25B, the Federal Transit Administration Passenger Ferry Grant Program will funnel $7.7M to Kitsap County Public Transportation to replace the passenger vessels Admiral Pete on the Port Orchard and Bremerton route. The new zero-emission, all-electric passenger ferry will reduce maritime emissions and will increase passenger capacity to better serve the more than 1,000 daily riders.

A pilot program created from the IIJA will give Washington ferries another $1.1B in financial assistance to transition to low emitting or electric vessels. The DOT is also providing $350M for basic essential ferry service. For example, $32M will go towards the 18 & Under Free Fare Policy in Washington.

Airports

Then Vice-President, Biden famously described New York City’s LaGuardia in 2014 as a “Third World country” airport. As a commercial fisherman, I understand the importance of working air freight. The first fish of summer get flown down south, while the rest travel the Alaska Marine Highway in refrigerated ships to far away destinations as the season progresses. Getting our beautiful wild red sockeye salmon to markets on time matters for the price we ultimately get paid.

The IIJA has budgeted $25B for Airports across America. Applications are open for the Airport Improvement Program. Seattle-Tacoma International has already received $228M, $32M has gone to Spokane International, and both the Tri-Cities and the Snohomish County Airport (Paine Field) will receive $16M. Most of the state’s airports, even tiny ones, get money from the IIJA. The grant format is intended to be flexible, allowing each airport to spend the money on what it needs most, like maintaining runways or for expanded operations, like terminal and gate construction, multi-modal projects, and low-emission ground service vehicles.

Passenger and Freight Rail

A new Railway Crossing Elimination Program is initiated through the IIJA. A resident of Edmonds, Washington, Cantwell has a particular rue for trains and cars blocking one another and creating safety hazards. Of the $3B for crossings across the nation, Washington will receive $5M. A recent report commissioned by Cantwell states that fixing fewer than half of the 50 highest-priority crossings in Washington would cost over $830M.

Major Projects: Dam & Culverts / Resiliency: Ecosystems

Washingtonians should be excited to see a line item for stream restoration, dam removal and bringing culverts up to salmon standards.

Washington DOT reported in June 2021 that the state has 3,965 highway crossings on fish-bearing waters, and over half are barriers to fish passage, including 2,040 culverts that are not adequately sized. State agencies are required by a court order to make road crossings navigable for fish again. According to estimates, it will cost between $300,000 and $1 million to replace each fish-barrier culvert.

Community-based restoration programs in Puget Sound will secure $400M for projects that support the restoration of fish passage by removing in-stream barriers such as culverts, small dams, dikes and other infrastructure.

The Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund (PCSRF) was awarded $172M to support habitat restoration projects for Endangered Species Act-listed salmon stocks in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, California, and Alaska, as well as federally recognized Tribes of the Columbia River and the Pacific Coast (including Alaska).

The National Estuarine Research Reserves System Program (NERRS) was given $77M, $20M was given to support NOAA’s environmental permitting process for restoration, and $56M for Regional Ocean Partnerships (ROPs), and several more programs will receive money to expand and develop.

Concluding Observations

As the funding for the IIJA gets winnowed down, I wonder how much is enough? Is $20M enough to build new traffic lanes at Blaine’s Port of Entry? Is this enough financing for the Northwest Seaport Alliance to break the top 10 international ports? What will the state’s airports do with the sum they’ve been given? It’s clear from the report Cantwell commissioned that the IIJA will not cover the cost of all the railway crossing projects. Nor will every culvert be remedied. And there are many more infrastructure areas that I know nothing about to say one way or the other. However, it is apparent that many of these agencies and projects have been funding deficient for a while.

Now that critical projects like the Ballard Locks, Tacoma’s off-dock support facility, and basic operating cost for ferries are addressed Washington ports can concentrate more energy towards long-term, just as important but less immediate, tasks. The Port of Seattle has set a goal to power every flight out of Sea-Tac International Airport with at least a 10% blend of sustainable aviation fuel by 2028. I consider this win for the IIJA, with funding for maintaining tarmacs, ports can spend on necessary aspirational projects. The Port has developed programs like the Duwamish Valley Community Benefits Commitment program and South King County Fund to address the disproportionate impact of operations on near-port communities. Clean port initiatives provide significant long-term benefits to communities as well as to the climate.

It should be noted that not all the funds have been paid out. The IIJA is still in the first round of distributing grants. Washington could still see more money coming our way. Washington’s large port sector makes the state a top contender for financing. As the year progresses it will be interesting to see what initiatives receive more grant funding.