COVID-19, Racial Justice, and the Duwamish River: Interviews with Environmental Stewards

Since time immemorial, the Duwamish Tribe has lived in what is now the Seattle and greater King County area, enjoying a close relationship with the Duwamish River. White settlers forced the Tribe out of the area, banned Native people from entering the city, and made massive alterations to the river’s lower reaches, literally paving the way for settlement, intensive agriculture, and heavy industry. White homeowners wrote racially exclusive covenants into property deeds to keep minorities out of neighborhoods north of the Ship Canal. Redlining practices diverted investment dollars away from communities of color for decades. This segregationist regime led to the growth of minority communities near what is now, due to decades of unfettered pollution, called the Lower Duwamish Waterway (LDW) Superfund site.

Located in South Seattle, the LDW is the most industrialized portion of the Duwamish River where the Green-Duwamish watershed drains into Puget Sound. For my master’s capstone, I’m working with fellow students in the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs (SMEA) to monitor a novel, “floating wetlands” restoration project in the LDW. It’s an updated version of a project that was monitored by other SMEA students last year.

As we got to know more about the project and Seattle’s segregationist history, some of us asked ourselves: How does this one small project fit into community goals for restoration and cleanup of the river? What are our obligations as non-Native, mostly white researchers to the diverse and underrepresented communities of South Seattle?

To get a better understanding of that context, I spoke to Sharon Leishman of the Duwamish Alive! Coalition, and David Bestock, Executive Director of the Delridge Neighborhoods Development Association (DNDA). I asked them about environmental and racial justice, and the effect COVID-19 is having on their work. I recognize and apologize for not being able to interview any non-white leaders in South Seattle in time for this piece, and I aim to do so for future pieces in Currents.

Lee: What does the Duwamish Alive! Coalition do?

Leishman: This is a very diverse coalition of organizations, municipalities, agencies and community groups focused on improving the health of the Duwamish watershed and the communities within it through collaboration. We need this collaborative approach to address the challenges in the Green-Duwamish, which has been designated as one of the top 10 most endangered watersheds in the nation.

Each of our partners focuses on a particular aspect of environmental health, and through our collaborative efforts we connect air and water quality improvement, habitat restoration, fish and wildlife, community, and justice and equity. Through this work we’re able to operate in a more holistic and strategic way, and we aim to make those connections for the public through education and outreach that fosters both environmental and community stewardship. To be successful, they must be considered one and the same.

Lee: How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the Coalition’s ability to carry out its work?

Leishman: Its effect on our communities and partners has been significant! Usually spring is one of our busiest times, where we focus on habitat restoration, improving water quality, education and fostering community engagement. This spring we were also celebrating the 50th anniversary of Earth Day along with our big spring event where hundreds of volunteers come together throughout the watershed to do restoration work. This was all canceled or postponed until at least the fall.

The pandemic has also hit funding resources very hard. Many of our partners depend on donations to support their work for improving the environmental health of our area and communities. These are some of the most racially and culturally diverse communities in the nation and they experience many of the issues rooted in social and environmental inequities.

Lee: What does the Delridge Neighborhoods Development Association do?

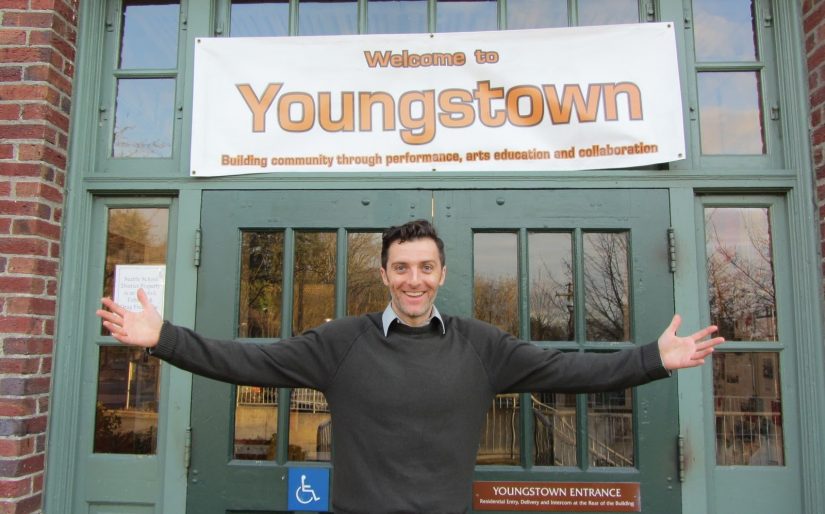

Bestock: DNDA has its roots in affordable housing. In the mid-2000s we funded intense renovations of the historic Cooper School and it’s now the Youngstown Cultural Arts Center. Launching Youngstown really added to the work of the organization and enhanced DNDA’s space as a place where youth and diverse communities can come together. It’s a really magical place and we’re very intentional about that.

DNDA is involved with Longfellow Creek, which flows to the Duwamish and runs all along Delridge. We have several restoration sites throughout the Longfellow watershed, including the Delridge Wetland Park.

Willard Brown, a former staff member, came to us with the idea of restoring a wetland that had been ditched and drained for Seattle City Light. Through our fundraising efforts, the land was purchased and deeded to Seattle’s Parks Department, but the agreement gives DNDA full site control for ten years. It’s only been two years so we’re still mid-fundraising and mid-construction. It’s a multi-phase project not just to build out the wetland but also to provide ways for the public to connect to it.

Lee: How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected DNDA’s ability to carry out its work?

Bestock: It’s been logistically and emotionally challenging. We made the call just before our March fundraiser to cancel it, and that was brutal for us both as a revenue loss but also just to lose a great celebration when we were nearly there. We also closed Youngstown in March. About 50,000 people come through Youngstown annually, and our rental spaces being closed is a significant loss of revenue.

We started producing online content through DNDA HeartSpace. The idea is to try to recreate the feel of Youngstown: one that’s very creative and collaborative, and a place for the community to gather. We have movement based classes, cooking classes, art challenges, and environmental lessons that all live online now.

Our justice-related activities shifted to supporting people’s basic needs. In partnership with the county and public schools, we’re shifting essential supplies and dollars to families in our affordable housing. We don’t normally do that kind of direct service, but since COVID-19 is highlighting existing economic and racial disparities, it’s something we are addressing.

Lee: The DNDA website features a solidarity statement in support of Black Lives Matter and the protests in response to the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black people by police. Can you talk about DNDA’s position at the intersections of community, housing justice, and environmental justice?

Bestock: We felt it was important to release a statement as an organization committed to anti-racism and justice work. However, a lot of Black organizations have asked people to decrease their communications and amplify Black voices instead, so we decided to limit our communications to a website statement.

Delridge is one of the most racially diverse communities in the city, so social and racial justice concerns are at the forefront, and it’s about environmental justice too. Additionally, there’s a problem with white environmentalists and researchers coming in to “save” communities. Through DNDA’s work, I’m invited to sit at a lot of tables. Given that opportunity, I see it as my role to raise my voice on behalf of others when I’m at those tables. But the point is that while we’re doing this work, it’s not about us. Ultimately, DNDA is trying to empower youth of color and foster the next generation of environmental stewards, to get them into nature and give them the resources they need so that they feel that nature is a place where they belong, and where they matter.

During my research and conversations, I’ve been struck by how settler-colonialism and racism have shaped the lower Duwamish and surrounding communities. While ecological restoration is worthwhile, it’s only a small piece of a larger, pre-existing movement to bring justice and equity to people and their environment.

COVID-19 creates a huge financial challenge for organizations that support South Seattle communities and restore their landscapes and waters. Meanwhile, a growing number are calling for a long overdue examination of the resources local governments spend on militarized policing, particularly in communities of color.

The time for policymakers to listen to movements is long overdue. It’s time to defund state-sanctioned violence and to reallocate public resources. It’s time to invest in our communities so they can properly heal.