A Gift of Conversation: Acknowledging Indigenous Land in Present-Day Seattle

We who live here invite you to feel

As the Old Chief, that the Great Spirit is Real

It’s Light — Sunsets from the Snows Gleaming Tower

It’s Color — floods the evening and shows forth its Power

Inspiring all to reach higher and higher

As they live by the Breath of the Cosmic Fire

–John Martin Rich, 1977

Let’s Pray. Great Spirit. Give Strength to our Native People. Bring Healing to our People. Protect our People. So be it.

Prayer offering at the Water of the Puget Sound from Layla Yamabe, the Director of Traditional Indigenous Medicine program at Seattle Indian Health Board. The prayer is in Northern Lushootseed and was gifted back to the people in the language by Jill LaPointe and LaPointe is the granddaughter of Vi Hilbert (Vi Hilbert taught the Luhshootseed Language at University of Washington for seventeen years).

The land acknowledgment is one of many cultural protocols that collectively make up a culture in the Pacific Northwest. It is a celebration, part of a long history of ceremony, a welcoming of People and Place. It is an opportunity to speak from the heart and embrace an openness and honesty with our past, present, and future. By cultivating acknowledgment of these things, we create the movement of good thoughts. In general, the land acknowledgment can be like an introduction of your place and role in the universe. Amongst Tribal Peoples, it is customary to introduce yourself in this manner, and then proceed to bring forward a dignified environmental history and cultural understanding of a particular people, watershed, or region. We, the authors, follow this custom below.

Good day. My full name is Michael Aaron Buck and my traditional name in Sahaptin from the Columbia River Plateau is Ka-Kin-As. My father’s name was Kenneth Puck-Hyah-Toot (Eagles Circling) Buck from the Wanapum (River-People) Band of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. My mother’s name is Carmen Rose Buck from the Nooksack River in Bellingham, Washington. Both my father and mother were raised in small villages along the Columbia and Nooksack Rivers, respectively. White Swan, Washington is where I was raised and is located on the western edge of the Yakima River Valley, just before the reservation begins to climb up towards sacred Mt. Adams, also known as Pah-to. I was born at the University of Washington Medical Center and, in essence, express a daily appreciation for Puget Sound.

Hello and welcome. My name is Thor Leighton Belle. I am a photographer, educator, captain, and storyteller. I value and seek to practice respect above all else. I am a brother to a sister, Katrina Belle, and a son to a mother, Schuyler Belle. They are both the strongest people I know. I grew up in South Bristol, a small fishing town in Maine and the ancestral home to the Walinakiak (People of the Bays) Abenaki Tribe. Family life wasn’t always easy, but throughout it all, I had the Ocean. I thank the Ocean that provides, and I thank the Winds that come down from all directions and carry us along our paths. I especially thank you, the reader, for keeping an open mind and heart as we move forward together towards a better, more equitable future.

Hello there. My name is Jazzmin Lee Fragiacomo, I am originally from the coastal town of Ventura, California, the ancestral home of the Chumash People. My father’s name is Steve, and he descends from Italian immigrants. My mother’s name is Christina, and she is the daughter of Irish and Mexican immigrants. My family was raised in southern California and much of my family still lives there today. I, however, currently live, work, and play in beautiful Seattle, Washington where I am always in awe of the beauty in the Land and Waters stewarded presently and pastly by the Duwamish, Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Suquamish, and Tulalip Tribes.

The three of us have come together to strengthen our capacity for learning, feeling, and sharing this history. Throughout this article we often refer to Land, Sea or other Places with a capital letter. This is to denote them as proper nouns or Individuals worthy of respect and rights in accordance with Natural or First Law. In what follows, we discuss the Lands, Waters, and some histories of the five Peoples and Nations currently local to the main three campuses of the University of Washington. In the spirit of gratitude, knowledge building, celebration, and healing we acknowledge the Duwamish People and the Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Suquamish, and Tulalip Tribes—as well as all Tribes in the Coast Salish region—as the original and continuing stewards of these Lands and Waters.

Currents’ Land Acknowledgment:

We at Currents are forever grateful to the many Tribes of the Coast Salish region—including but not limited to the Duwamish People and the Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Suquamish, and Tulalip Tribes. The Land and Sea of this region is connected to the body, heart, and lives of these Peoples and has been since time immemorial. We seek to uplift the strong Sovereign Nations of the Coast Salish region and their right to Self-Determination. We remember and thank these Peoples: past, present, and future.

We recognize that this acknowledgment is only the beginning of a conversation of actions, awareness, and connection. We strive to meet these conversations with an eye to the diverse perspectives and knowledges of this region’s many Tribal Nations. We intend to do so with respect, reciprocity, relevance, and responsibility for ALL OUR RELATIONS.

Duwamish

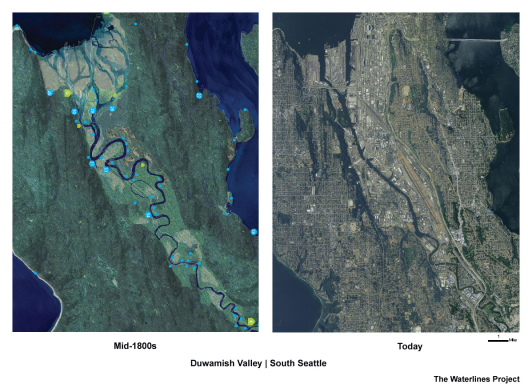

The Duwamish (doo-WAA-muhsh) People, Dxʷdəwʔabš, or “People of the Inside” are the hosts of the city of Seattle. The Inside People, Saltwater People, River People, and Lake People are distinct groups that came together as the threat of settlers grew in the 1800s. Their connection to this Land and Water has flowed through time along with the Dxʷdəw (Duwamish) River.

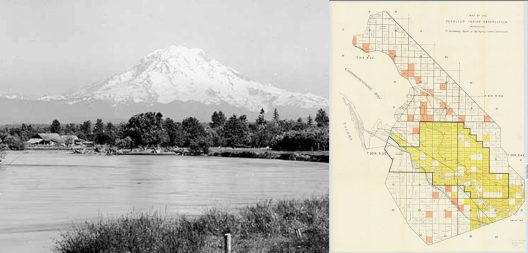

Her many meanders once cut across the fertile plains from the foothills to the Sea’s edge. Vast grasslands glimmering with the refracted light of an immeasurable number of ice crystals on a frosty morning, thousands of acres of marsh, and crucial fish runs that supported everything from orcas to mice. Replaced by innumerable light bulbs, acres of pavement, and polluted channels to nowhere. The Land is changed, the Water tainted, and yet the Dxʷdəwʔabš are here. The Duwamish People still care for the Land and Water as their ancestors did before them. Working closely with King County and other partners, they lead a variety of restoration, community building, and advocacy initiatives.

Most of the Duwamish People moved from the area we now call Seattle to live in the Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Tulalip, Suquamish, and Lummi Tribes as they were forced out of the growing city by settlers in the mid to late 1800s. Today the Duwamish lack federal recognition despite being the first signatories of the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855, one of the eight treaties commonly referred to as the Stevens Treaties. This lack of recognition adds layers of difficulty for the Duwamish People and their struggle to advocate for and steward their ancestral lands. While we acknowledge that there are many complexities surrounding the discourse of this recognition, we recognize the Duwamish Peoples as some of the original residents of the area we now call Seattle and thank them for their continued stewardship of the Land and Sea.

Muckleshoot

The name Muckleshoot (MUCK-uhl-shoot) is derived from the name of a reservation established in 1857 by President Franklin Pierce. A grouping of several tribes forced to live together, they later became known as the Muckleshoot Tribe and therefore have no original Lushootseed word for the grouping of tribes. Even still, the Muckleshoot people have unique ways of expressing gratitude to their families, foods, and culture. A friend and fellow historian named Warren KingGeorge is a well-versed representative and historian of the Muckleshoot Tribe. Warren is also a respected plant medicine and medicinal food gatherer of this territory. Prior to the Treaty of Point Elliott and the Treaty of Medicine Creek, the Muckleshoot maintained their identity through bio-cultural knowledge of Puget Sound.

Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge (ITEK) is knowledge that transcends generations and is maintained through annual ceremony and seasonal gathering. Just as most, if not all, tribes in the region of King County and Seattle, the present-day Muckleshoot identify themselves as Salmon People. ITEK from Elders and food gatherers like Warren recalls stories of the survival of the Muckleshoot: “In their hour of need, our tribe sent a boy into the river and he became a salmon, bearing a message from the tribe. He swam into the deep ocean to beseech the salmon people for help.” According to their history, the salmon people of the deep sea answered their prayers by returning every year from the ocean to the White River, providing a bounty.

Puyallup

The Puyallup Tribe (pyoo-A-luhp) has existed along the verdant shores of the Salish Sea for as long as Wind has pushed upon the Land and Sea. Puyaləpabš, or “People at the Bend at the Bottom (of the river)” have cared for and stewarded the Land we all now call home. The University of Washington’s Tacoma Campus is located on the ancestral Lands of the Puyallup People.

A leader in environmental stewardship, community support, economic development, outreach, and education, the Puyallup Tribe builds off the legacy of their ancestors as stewards of the Earth by combating the modern threats of climate change and ecological degradation. They are leaders in restoration efforts throughout the south Salish Sea and champions of the environment, embracing and implementing the Paris Climate Agreement and preventing regressive developments like the Tacoma LNG project. This past February, the Tribe won a legal battle that ensured the unimpeded migration of endangered Chinook salmon, steelhead, and bull trout along the entire length of the Puyallup River for the first time in over a century. Without the Puyallup People, their hatcheries, restoration efforts, environmental protection initiatives, and co-management of natural resources, our environment would be changed beyond our current recognition.

Suquamish

Agate Passage, the Place of the Clear Salt Water, is a tidal straight in central Puget Sound near Port Madison that has been home to the Suquamish (suh·KWAA·muhsh) Tribe—Dxʷsəqʷəb “People of the Clear Salt Water.” Today, the 7,657-acre Port Madison reservation is home to many Suquamish people as well as non-native people. It is unclear how much land was allocated for and owned by the Suquamish Tribe after the signing of the Treaty of Point Elliott, but it is clear that the reservation was much larger than it is today. Due to federal mandates and the passage of the Dawes Act in 1887, reservation lands held communally by all tribes, including the Suquamish Tribe, were converted into individual family parcels. Land not allotted, or if families could not afford taxes and payments after the held in trust period, was sold off for cheap to non-native buyers.

The policy of implementing small plots of allotted lands to families within the tribe was an attempt to disrupt the communal living of all tribes and to break up reservations. Because of this, the Port Madison reservation is inhabited by a mix of native and non-native people. This history is not unique to the Suquamish people; in fact, it is a common history lived and felt by tribes throughout the U.S. as the assimilation of native peoples to “American” society was a dominant policy goal of state and federal governments in the 19th and early 20th century.

Tulalip Tribes

Tulalip (tuh-LAY-lup) comes from dxʷlilap, which means “Small-Mouthed Bay”. The Tulalip Tribes encompass descendants of the Skykomish, Snoqualmie, Snohomish, and Stillaguamish Tribes. The Tulalip reservation and its boundaries, located north of Everett and west of Marysville, were established by the Point Elliott treaty and outlined which tribes would reside there. Though the boundaries of the reservation are partly within the Tribes’ usual and accustomed lands, the reservation is but a small fraction of the original territory where the Tulalip Tribes lived, worked, and played prior to the Point Elliott Treaty. These ancestral lands stretched across present-day Oregon, Vancouver, B.C., the Cascade Mountains, and likely to some Puget Sound islands such as Camano and Whidbey Islands. These Lands and Waters in between them were more than a means for hunting, fishing, and living for the Tulalip Tribes—they cultivated, stewarded, and shaped these Lands into their home.

Through the Point Elliott Treaty, the Tulalip and other tribes ceded their lands to the U.S. government in exchange for designated plots of land, sovereignty, and money. Despite the treaty reserving the hunting and fishing rights of the Tribes, they have endured violent challenges to maintaining access to ancestral Lands and foods, such as forced enrollment into boarding schools—which limited the generational passage of cultural heritage—and the active exclusion to usual and accustomed fishing and hunting grounds. Recognizing and acknowledging the past and present stewardship of Coast Salish ancestral Lands is a step toward confronting our colonial past.

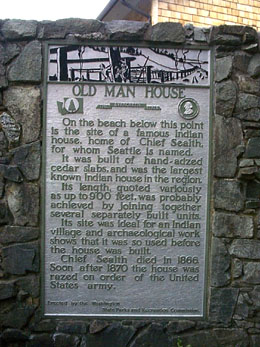

“Every part of this country is sacred to my people. Every hillside, every valley, every plain and groove has been hallowed by some fond memory or some sad experience of my tribe. Even the rocks, which seem to lie dumb as they swelter in the sun along the silent sea shore in solemn grandeur, thrill with memories of past events connected with the lives of my people.” – Chief Seattle

For decades upon decades, Indigenous or Tribal People in this country were not allowed to pray, and the most common understandings of prayer can sometimes trigger discomfort in an academic space or institution. The land acknowledgment is a prayer, and in the spirit of sharing the contemporary intellectual tradition of Native people today, we offer a simplified way of thinking. Prayer in this context can be thought of as the movement of good thoughts. Indigenous Tribal leaders from the Pacific Northwest tribes acknowledge Water and Land communities through prayer and song each day as individuals as well as collectively at organized community or ceremonial events.

The resurgence of the land acknowledgment practice and prayer and its adoption by settler institutions speaks volumes to the shift in beliefs and policies toward Indigenous Tribes in this country. These acknowledgments not only allow for the sharing of ideas or signal mutual respect, but they are also a gift—a starting place for healing. The U.S. has a long history of ignoring or actively working to erase the existence of Tribal Nations. To this day, our colonial conditioning remains strong. Yet, the land acknowledgment is a powerful gift that provides us a path to heal and reconcile this conditioning, as well as our past.

For continued education and ways to participate, we have provided some resources to get you started.

- LANDBACK Movement.

- On Our Terms Project, 12 participants define 10 key decolonial terms and what they mean to them

- Assimilation Through Education: Indian Boarding Schools in the Pacific Northwest

- Maps of Historical Federal Indian Boarding Schools

- About Lushootseed/Twulshootseed Language

- Felt Theory – An Indigenous Feminist Approach to Affect and History by Dr. Dian Million

- The Fish-in Protests at Frank’s Landing, A history of the events leading to the 1974 Boldt Decision

- The Fight of the Salmon People, How the Land Was Lost, How the Fish Were Lost, How Recovery Failed, A New Promise

- Salmon in the Pacific Northwest, History Link Essay

- The Oregon Coast—”Forists and Green Verdent Launs”: An 8-Part series, Oregon History Project

- What is Indigenous Data Sovereignty?

- Salmon Boy (Coast Salish), A traditional story told by Roger Fernandez about the importance of salmon and out relationships with them

- Indigenous Walking Tour, Developed by a former UW student, the Indigenous Walking Tour is designed to highlight Indigenous presences on campus and educate the participant on the history of the land UW stands

- Native-Land is an interactive map that maps the indigenous territories, languages, and treaties

- Real Rent Duwamish compensation for land, resources, and livelihoods