Field Science in the Arctic Ocean: An Inside Look

The first in a series illustrating researchers’ experiences at sea

By Kaitlin Lebon

It’s 11pm, and for Kylie Welch— a Faculty Research Assistant with the Goñi Lab at Oregon State University (OSU)—the day is just beginning. She walks from her cabin to the galley and grabs a snack. As she looks out a porthole onto the cold Arctic water, she prepares for another twelve-hour shift of sampling.

It’s 11pm, and for Kylie Welch— a Faculty Research Assistant with the Goñi Lab at Oregon State University (OSU)—the day is just beginning. She walks from her cabin to the galley and grabs a snack. As she looks out a porthole onto the cold Arctic water, she prepares for another twelve-hour shift of sampling.

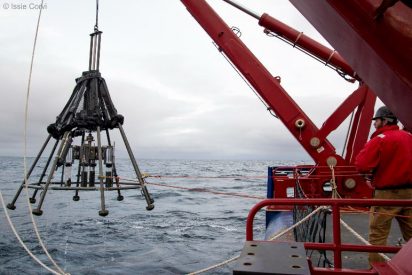

A native of Bend, Oregon, Kylie first began working with oceanographic research as an undergraduate at OSU while pursuing an honors degree in biochemistry/biophysics. Since graduating, she has been hired to a full-time position overseeing daily research tasks as lab manager. When asked about her experience, Kylie states, “During my time as a student, I worked on various projects and learned a lot about the different processes and procedures involved in the day-to-day operations in the lab. Now, my duties involve supervising undergraduate students, field work, instrument running and maintenance, sample tracking, ordering laboratory supplies, and other daily operational tasks.” This job brought Kylie to the Arctic where she has spent her last two summers studying oceanographic conditions on the R/V Sikuliaq, a 261-foot research vessel. Now it is 12am, and Kylie starts her shift sampling the sea water of the Arctic.

In the world of oceanography, going out to sea is relatively commonplace. Field research is vital to understanding how humans are changing the planet. This is especially true in the Arctic, where ecosystems feel the effects of human activities despite being well away from most of the world’s populations. Sampling areas that were once thought to be pristine ecosystems will help scientists better comprehend the full scope of anthropogenic impacts. As such, the work Kylie completes during her twelve-hour shift will not be for nothing. Although oceanographic research assistants can be found in waters around the world, Kylie is one of the few lucky enough to have worked in remote Arctic waters. The samples she collects are used for the Goñi Lab investigation of carbon and nutrient cycling to help answer questions about how productivity in the Arctic Ocean is affected by differing seasonal oceanographic conditions.

Kylie described the work that brought her to the isolated Arctic: “There are several lines in the Arctic that have been studied by a variety of groups over a long time which is good for establishing seasonal or temporal patterns and changes, especially with record lows of sea ice that impact ecosystem productivity. It has been shown that parts of the Arctic are more productive than others, and part of what we want to look at is if there is late season productivity and how it might impact the food chain.”

Sampling in the Arctic for two years, Kylie is no stranger to how dynamic this area is. The variability of sea ice affects the scientists’ ability to work consistently: “Last year, our sampling occurred mainly in September and we saw a lot of sea ice. That had its own impact on our science as we had to move around a lot to avoid the ice and our sampling path changed quickly and often. Additionally, sea ice meant we saw different wildlife—polar bears and walruses! This year the cruise took place mainly in August and we didn’t see any sea ice. We didn’t see wildlife beyond birds and jellyfish, and our cruise path was consistent.”

In addition to changing sea ice conditions, scientists must navigate politics of conducting research in areas people’s livelihoods depend on. As Kylie remarked, “One thing most people forget about science is how people and politics can impact the way science is carried out. For us, there was a lot of discussion between the chief scientists and the native Inupiat people about where and when we were allowed the sample. They were concerned about us scaring away the whales during their whaling season, so we had certain restrictions on our sampling.”

While much of the field work revolves around water sampling, part of the cruise focuses on collecting sediment cores. Erin Guillory, an undergraduate member of the Goñi Lab, is using these sediment cores to look for microplastics—a growing problem worldwide. The Arctic is no exception despite its relative remoteness. Kylie, along with her fellow Goñi Lab members, is among some of the first to look for microplastics in Arctic sediment and hope their data can serve as a baseline for monitoring further anthropogenic impacts on oceans.

Science on board the Sikuliaq is a ‘round-the-clock-job—literally. When Kylie is finally done with her shift at 12pm, other scientists are there to take her place for the next twelve hours. As Kylie winds down from a long night of sampling, she stops to talk with Sikuliaq crew and visiting scientists commingling in the galley. She heads back to her cabin to read for a bit before going to sleep to prepare for another night filled with science.

Photographs courtesy of Issie Corvi, student researcher and member of the Goñi Lab: http://issiecorvi.wixsite.com/issiecorvi