Clearing the Way for Salmon: The Difficult Path to Removing Dams in the Klamath Basin

By Spencer Showalter

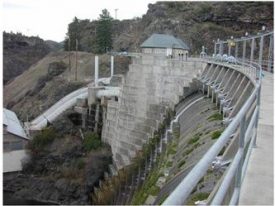

Mark your calendars for 2020—it could be the beginning of the largest dam removal project in American history. While dams in California have been used for generations to stabilize long-term water availability to settlers, their inherent role of restricting flow affects humans and ecosystems downstream. Because of these impacts, four dams in the Klamath River Basin are slated to be removed in a $450 million project that would re-open 500 miles of spawning grounds to coho and Chinook salmon. The gains from the removal could be huge. Reopening spawning grounds would help rebuild depleted salmon fisheries, and higher flow would mean cleaner water with fewer viral infections and toxic algae blooms. Because the future costs of upkeep of the dams represent a net loss to their owner, PacifiCorp, removal would be economically positive in a corporate sense. Additionally, the water and salmon fisheries were historically used by native tribes of the Klamath Basin, including the Yurok and Karuk Tribes, who stand to regain clean water and increased harvests if the dams are removed.

However, since their construction spanning 1912 to 1964, the reservoirs on the dammed Klamath River have been the main water supply for roughly 1,600 farmers in both California and Oregon, who use the water to irrigate 200,000 acres of land. Due to the losses that farmers would face following demolition of the dams, this project has resulted in multiple decades of controversy, and the path has not ended: demolition has yet to obtain the required approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

Unfortunately, the construction of the dams brought a host of environmental issues to the Klamath river basin. The dams inhibited spawning routes of Chinook and coho salmon, the latter of which were subsequently listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 2005. Additionally, warm waters allow the proliferation of Ceratonova shasta, a parasite that is lethal to salmon. Low flow and warm waters result in blooms of toxic blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) that have made much of the river dangerous to swim in. The dammed water also supplies irrigation to a large area of farmland, and the history of the dams is fraught with the inherent tension of keeping the lower Klamath clean, cool, and running, while simultaneously irrigating fields.

In 2001, historically low water levels in the Klamath basin led to closures of flow gates. Farmers mounted protests, eventually blowtorching open canal gates so they could irrigate their lands. In response, the Bureau of Reclamation allocated more water to farmers in 2002. However, incredibly low flow rates lead to an outbreak of C. shasta, resulting in the death of nearly 68,000 salmon, creating even more problems. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service identified the low flows as a major culprit in the fish kill, providing impetus for the tribes that have fished the Klamath for generations to advocate for dam removal.

Thus began a series of negotiations and attempts at coalition-building. While farmers claimed senior water rights, the Klamath Tribes of Oregon filed a lawsuit. The court ruled in favor of the Native American tribes, upholding their “time immemorial” priority date for water claims. The judgement in the suit required maintenance of in-stream water levels to prevent future devastating viral outbreaks. Meanwhile, PacifiCorp acknowledged that its dams were outdated and beginning to lose money and agreed that dam removal was the best economic decision for its shareholders.

A plan was drafted in 2015 to restore the Klamath river basin, which included the removal of four dams, restoration of salmon habitat, the return of tribal lands to tribal peoples, and a water-sharing agreement among farmers, ranchers, and tribes. However, the plan required Congressional authorization and funding, and when Congress refused to make a move on the bill—citing concerns that it would threaten the future of the Hoover Dam—it eventually expired.

In 2016, a new agreement to create the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC) was signed by tribal chairs of the Yurok, Karuk, and Klamath tribes, the governors of Oregon and California, the Secretary of the Interior, and PacifiCorp. PacifiCorp has applied to FERC for the ownership of the dams to be transferred to the KRRC. KRRC subsequently applied to decommission the dams by 2020. Neither application has yet been approved by FERC, which is tentatively considering who would hold long-term liability for the dam removal process.

For now, the future of the Klamath dams rests with a committee appointed by President Trump, but keep an eye on this story—the tension over these water rights is not going away.