Why is the West Coast so Crabby? Exploring the Relationship Between Community Collaboration and Coastal Management

I shouldn’t be surprised that the one constant theme through my two years at SMEA is the complexity of coastal management issues that we spend so much of our time attempting to understand and solve. As an environmentalist and animal enthusiast, I typically find myself favoring management strategies that conserve these species and the spaces they rely on. But despite my love for all of our ocean’s marine critters, I recognize that these species aren’t the only ones using and benefitting from these spaces, and our coastal communities and their fisheries, too, have an important place in coastal resource management.

Before I ever walked through SMEA’s doors, and frankly since I was a very little girl, I have been enchanted by the mighty humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). The way they glide, dive, and lunge their 35-ton bodies vertically out of the water, putting on intricate aerial dances, is one of the most beautiful displays nature has to offer. So you probably won’t be surprised when I say that once I stepped foot into SMEA, I was immediately pulled towards gaining a better understanding of these aerial artists, the West Coast management issues they find themselves starring in, and gaining a better understanding of what real-world collaborative management looks like.

For many years, the West Coast’s Dungeness crab fishery has been an economic powerhouse, cultural icon, and critical pillar of coastal communities in Washington, Oregon, and California. But as the impacts of anthropogenic climate change sweep throughout the Pacific Ocean, the foundation of this once stable system is shaken by changes in marine ecosystems that have entangled some of the ocean’s most beloved behemoths. Changes in coastal prey availability and shifts in migratory patterns have caused endangered Central American humpback whales to swim right through a gauntlet of Dungeness crab pots. This shift in humpback prey location and its overlap of the Dungeness crab fishery has coastal groups searching for a management solution that will not only safeguard the economic value of the fishery, but halt the swim of the Central American humpback whale population towards migration.

For much of the fishery’s existence, West Coast fishers have shared the art of crabbing from generation to generation, sharing in the local knowledge of their communities and keeping a rich tradition alive. To best understand the fishery and find success season after season, crab fishers have maintained these knowledge pipelines by collaborating on where and how to find these clawed bottom-dwellers.

Labeled by some as one of the West Coast’s “forever fisheries” due to its perceived sustainability, the Dungeness crab industry is a foundational component of the Pacific states seafood markets and is one of their largest fisheries. The three states collaboratively manage the fishery together–while continuing their own individual coastal management–to create robust rules which protect the future of the fishery including size, sex, and seasonal time limits that typically run from mid-November through mid-July of the next year. Fishery management also guides the type of allowable gear, the number of pots allowed per vessel, and how many permits are released each season.

Throughout this period, crab fishers will head out of port to distribute their pots throughout coastal waters in search of profitable hauls of crab. These pots are placed on the seafloor where they will cleverly use the crab’s scavenger instincts to cause it to trap itself. Throughout the season, Dungeness crab pots that are placed along the seafloor and retrievable via long ropes attached to buoys at the surface are scattered along Washington, Oregon, and California’s coastlines and create an obstacle for species navigating these crowded waters.

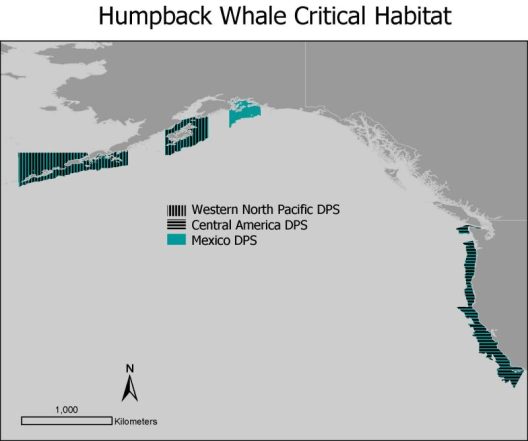

Re-enter the humpback whale. Commonly seen as one of the Pacific’s most charismatic megafauna, humpbacks inhabit oceans across the globe, entrancing whale enthusiasts–including myself–with their graceful aerial displays. While the Pacific Ocean is home to multiple groups of migrating humpback whales, the group responsible for the migration pattern throughout the California Current’s Dungeness crab fishery is the Central American humpback whale population. This population has moved from “threatened” to “endangered” status under the Endangered Species Act and is one of the more sensitive baleen species in the Pacific Ocean.

After a winter spent in their breeding grounds off the coast of Central America, the Central American population will migrate north to the icy waters of Alaska to feed throughout the summer. This migration route has these whales moving along the United States’ west coast during the last few months of the Dungeness crab season, swimming directly through a coastal zone littered with pots, thick ropes, and floating buoys. In the last two decades, humpback whales have made up over 58% of reported entanglements throughout coastal zones due to unintentional overlap with coastal crab pots.

Because the Dungeness crab season typically is open between November through July, migrating humpbacks who re-enter these coastal zones on the tail end of the season have historically not experienced many entanglement issues. But as abnormal marine heat waves become more common throughout the eastern Pacific, a shoreward shift in prey availability has the Central population arriving earlier in the season, lingering along shallow coastal zones in search of a meal, risking entanglement. With the Central American population shifting their migration return time to be earlier in the year and overlapping with the end of the Dungeness season, whale entanglement has become a recurring issue that leaves fisheries managers and environmentalists at odds. For the last 10 years, these entanglements have often prompted the premature shutdown of the Dungeness crab season to protect humpbacks as during their migration, leaving crab fishers frustrated with a shortened season.

So what does that look like from a management perspective? What perspectives and voices may be missing and therefore must be incorporated into management decisions for success? What does a solution look like that allows for both parties to meet in the middle and benefit from new management decisions? Anthropogenic climate changes and whale entanglements have those in support of marine mammal protection and the Dungeness crab fishery at odds as they grapple with figuring out how to preserve the Central American humpback whale population while preventing continued economic harm to the crabbers within the fishery.

Initial prevention strategies included delaying the fishery’s opening date or premature closure of the Dungeness crab season which unfairly placed economic hardships on West coast crabbers to protect endangered humpbacks. Crabbers throughout Washington, Oregon, and California became frustrated with these decisions, stating the change in season was not sustainable for long term profit, and insisted on the development of new strategies that would not place all the burden on their shoulders.

Over the last 10 years, there has been an increase in conversation and collaboration between these two groups through the creation of management working groups and new solution-based regulation. One example of this collaboration is the creation of California’s Dungeness Crab Fishery Working Group and its Risk Assessment and Mitigation Program which would act as a collaborative working group of commercial and recreational fishers, environmental and NGO participants, and state and federal agencies who would collaborate to quickly identify and respond to entanglement possibilities.

In addition, many management stakeholders have suggested an array of possible solutions that could alter the future of both the Dungeness crab fishery and Central American humpback whale population. “Ropeless” or “pop-up” gear is just one of these solutions and could be effective because it eliminates the thick ropes that humpbacks are often tangled in. Within the last year, the California Ocean Protection Council has funded over $3 million in whale entanglement prevention programming that will incentivize the use of these pots to minimize harm. Their work also prioritizes investment in strategic planning that will minimize biological harm and that incentivizes crab-fishers to participate in the use of new crabbing technologies. These plans will utilize continued stakeholder collaboration, heightened community outreach for entanglement response and sharing of fishery information, and best available science to propel gear modification innovation forward.

After diving deeper into the complexity of the humpback whale’s place in the West Coast’s Dungeness fishery, what stuck out most to me was the collaborative nature of this management issue. While there were initial frustrations in both parties about how this issue was being handled, stakeholders from both the marine conservation field, as well as crabbers from the fishery itself, came together to have solutions-based conversations.This type of collaborative, solutions-based work is just one of the many examples of how stakeholders can come together to collaborate to protect not only the needs of themselves, but the needs and interests of all parties involved. Through this work, the collaboration of diverse perspectives that prioritizes both local and traditional knowledge, is critical to the success of these decisions into the future. As a marine enthusiast and environmental optimist, my hope is that as anthropogenic climate change continues to affect our marine ecosystems, the collaborative work along the West Coast can continue to push fisheries management forward while continuing to safeguard and prioritize the Pacific’s beloved marine mammals.

The following sources were used that may be behind a paywall, please contact the Currents Editor-in-Chief for access.

Seary, R., Santora, J.A., Tommasi, D. et al. Revenue loss due to whale entanglement mitigation and fishery closures. Sci Rep 12, 21554 (2022). https://doi-org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/10.1038/s41598-022-24867-2