Offshore Timber: The Reindustrialization of Pacific Coast Logging Communities

Along the Pacific Coast, small towns dot the rugged coastline from San Francisco to Seattle. Built on fishing and logging, these extractive industries were foundational to the economy and construction of the Pacific Northwest. As traditional industries contracted due to over-exploitation of resources, mechanization of labor, and changes in demand, the west coast became more urban. The US west coast is now defined by the tremendous growth of its tech sector titans: Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, and Google. Economic opportunity has drawn our population towards urban developments while the decline of traditional industries has left the rural towns of the Pacific Coast struggling with fewer family wage jobs, consolidation of industries, and the economic challenges of supporting an aging population. Now, the US government, in an effort to tackle carbon emissions in the energy sector, has implemented a strategy to develop the largest floating offshore wind farms in the world off the coast of the small cities next to Coos Bay, Oregon and Humboldt Bay, California. With the potential for billions of dollars of new investment and a reindustrialization of coastal communities we must ask; will these communities be revitalized by the benefits of renewable energy development or will they be left with negative environmental impacts while profits are funneled to the headquarters of large multinational corporations?

Pacific Northwest Timber Legacy

The legacy of timber in the Pacific Northwest has to begin with its original caretakers, the Indigenous peoples. Sustainably managed for thousands of years, cedar was used to build longhouses, canoes, and clothing. Western settlers found a plethora of natural resources on arrival that began a gold and timber rush which lasted over 100 years. In the second half of the 20th century, repercussions of timber industrialization were felt through lower salmon returns, degraded streams and estuaries, and the decline of the Northern Spotted Owl. As forestry management practices changed after the Second World War, logging area was curtailed by the US Forest Service, and state forestry agencies. After the listing of the Northern Spotted Owl and other endangered species, court injunctions caused the cessation of timber harvest in 10 million hectares of federal forest lands in the early 1990s. The Northwest Forest Plan was implemented in 1994 to sustainably manage the federal forests that stretch from San Francisco, California to the Washington-Canada border.

In Humboldt County, California, logging and fishing peaked in 1979. However, logging employment had been contracting since the 1950s. The symbolic end of the logging industry began in 1990, with a three month protest movement called the “Redwood Summer.” After over 95% of old growth redwoods had been logged, Earth First! and the Industrial Workers of the World utilized tree sit-ins, disarmed machinery, and protested to slow or stop further destruction of old growth forests. A parallel movement sprung to action with California Proposition 130, a ballot measure that proposed placing tighter restrictions on logging and providing a mechanism to use public funds for the purchase of “ancient forests” to preserve wildlife habitat. The Redwood Summer activists predicted a rush of timber felling before the ballot and took action to protect the forest. The bill failed, but continued pressure through protest and lawsuits alleging inadequate environmental impact assessments, slowed old growth logging. This led to the eventual sale of the disputed forests to the government in 1999, establishing the Headwaters Forest Reserve.

Today Humboldt County has a ~18% poverty rate, even though it has a large state university, a burgeoning art and recreation scene, and substantial tourism with Redwood National Park just a few miles away. With decreased forest area available to harvest, smaller fish stocks, and the mechanization of extractive industries, the economy of the area has moved towards cannabis, healthcare, retail services, and public employment. In 2022, Humboldt County gross timber sales were $99 million, dwarfed by cannabis cultivation sales of $310 million. The switch to a service economy in the US has reduced heavy industry and manufacturing across the country, with logging and fishing bearing the brunt of job losses in the coastal PNW.

Just 200 miles north of Humboldt, along Highway 101, Coos County, Oregon had a consolidation of timber producers in the second half of the 20th century. In the 1970s, the southern Oregon coast boasted dozens of sawmills—today there are only two. This decline is not unique to Oregon—in the western United States close to 40% of logging jobs were lost between 1997 and 2017, and the trend has continued into the present day. Coos County lost another 16% of lumber jobs from 2019-2023, the highest of any sector in the county. Though mechanization and efficiency improvements are the main reasons for the industry’s decline, now demographics of the regions play a large role in employment contraction. Between 2002 and 2022 the 65+ age demographic in Coos County has gone up 51%, as the prime working age demographic of 35-49 has decreased 19%. The rural coastal areas lack dynamism in the local economy which has led to the exodus of young Americans toward the metro areas which have higher pay, more social services, centers of culture and art, and more people of their age. Poverty in Coos County, Oregon (16.5%) and Humboldt County, California (18%) remain elevated compared to the US national average (12.6%).

Community Desires and The Housing Crisis

This summer I had the opportunity to interview citizens of Coos Bay, Oregon and Humboldt Bay, California about what they believed were the current challenges and opportunities for the region. I chose this region because of the massive federal initiative to upgrade ports to accommodate the construction of thousands of offshore wind turbines, each taller than the iconic redwood trees of the region. Interviewees loved the rural character of their communities; a beautiful environment, little traffic, soaring coastal cliffs and forests for hiking, hunting, biking, and enjoying the local flora and fauna. Many expressed a desire for greater economic opportunity, family wage jobs, increased transit and healthcare options, and autonomy for the community to chart its own path separate from federal and state politics–which they believe often casts them as second class citizens in policy discussion. Some interviewees had their children leave the area for jobs and education opportunities that were unavailable in the region, which has led to the dissolution of the traditional close knit intergenerational communities that were once common in this area.

Each interviewee had different priorities for what they believed would help the community most, though most agreed a better economy would be beneficial, especially for keeping young people in the area. In contrast, there was near uniform agreement on the main issues these rural coastal communities faced, affordable housing, homelessness, and poverty. All interviewees expressed one, or a combination, of these concerns.

In southern Oregon, the Home Price Index (HPI) has increased from below $150,000 in 2011, to $350,000 in 2023, a 133% increase in price. Meanwhile, wages have not kept pace, with a Median Household Income (MHI) of $36,500 in 2011, growing to $56,000 in 2022, a 53% increase. Similar housing prices to wage ratios are found all along the Pacific Coast with MHI increasing 45% and HPI 83% in Humboldt County, CA. To avoid being “housing burdened” residents would need to make ~$83,000 per year, a 48% wage increase in MHI to afford the average mortgage payment for an average home. However, a glimmer of economic hope can be caught on the waves of the Pacific Ocean, flashing atop the crest of a new reindustrialization wave headed toward the region. As the US tries to reduce its fossil fuel use to decelerate climate change, offshore wind energy has the potential to provide family wage jobs and economic growth along the Pacific Coast.

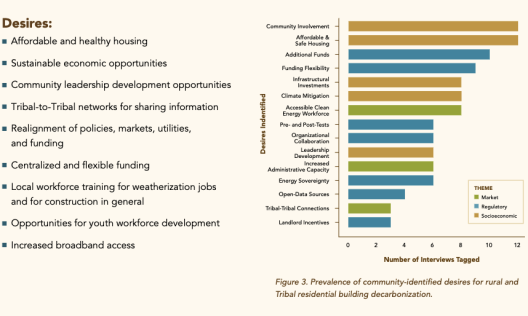

The Clean Energy Transition Institute has done research on community defined decarbonization and found affordable housing to be the number one concern, along with community involvement, associated with building decarbonization in rural and tribal communities (Fig. 1). Development initiatives and policies therefore need to provide flexibility of funding mechanisms for community benefit plans and allow the desires of the community to drive investment.

Energy Opportunity, and Reindustrialization

As our nation moves towards new clean energy sources, the wind blown Pacific Coast has become a target for offshore wind energy developments. The Biden-Harris administration has set targets of 15GW of floating offshore wind by 2035, and up to 110GW of total offshore wind capacity by 2050. This new industry has the potential to create the blue collar family wage jobs lost during the decline of the timber and fishing industries. According to the research by a Net-Zero Northwest study, if the Pacific Northwest develops the electrical capacity to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, there would be a 17% increase in jobs in the energy sector by 2030. Currently, loggers in Coos County make ~$55,000 per year, while electricians and linemen make between $74,000-$114,00 a year. These family wage jobs could help offset the skyrocketing price of housing across these communities. The range of pay of electrical utility workers is much closer to the needed earnings (~$83,000) to allow workers and families to purchase homes in the region without being housing burdened (defined by the federal government as >30% of income going to housing cost).

Not only could energy jobs be better paying but many of the components and facilities necessary for construction would have to be built at the ports due to their massive size. This would encourage economic growth in the construction and engineering sectors as well as bolster union jobs in the maritime and machining industries. The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory recently completed a study that estimated a net economic benefit to northern California and southern Oregon between $127 million to $6 billion. The combined real GDP of Coos and Humboldt Counties is $8 billion. This might not be an addition to the economy of these areas but a wholesale regional transformation.

Policy Choice, Community Values

On January 23rd, 2024, U.S. Senators Alex Padilla and Laphonza Butler of California, and Representative Jared Huffman (D-Calif. 02) announced a federal grant for $426.7 million, with Crowley (a private maritime company) matching that amount to fund the Humboldt Bay Offshore Wind MVP (Minimum Viable Port) project. This $853 million investment will allow the first floating offshore wind (FOSW) integration port on the west coast, with a planned completion in 2028-2029. The port estimates it will be able to integrate one floating turbine per week after completion, enabling the offshore wind energy goals of California and the US to reach fruition.

Though many of the decisions about offshore wind reside at the federal level these projects will not succeed without the buy-in of local communities. Because FOSW still has technical and engineering challenges before construction can begin, the West Coast has been given time to engage in meaningful consultation with local communities to center their values during this new offshore wind opportunity. We must not squander that opportunity. By centering benefits on the most important issues in these communities like housing affordability, community involvement, and funding flexibility we can lay the groundwork for a just energy transition along the Pacific Coast.

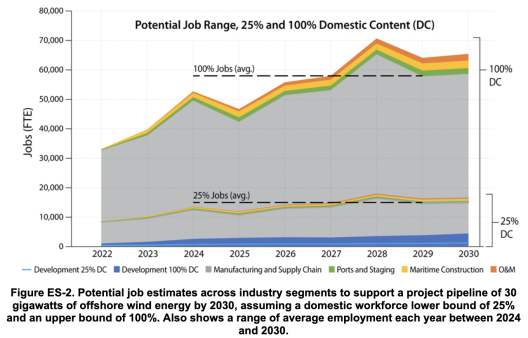

With the potential for hundreds of jobs, and a stable industrial manufacturing base on the horizon, many are rightly excited that offshore wind could revitalize the economy of the region. But to avoid the increases in poverty, drug addiction, environmental degradation, and community dissolution during the decline of past extractive regimes (lumber and fishing) careful consideration must be made about where facilities will be built, how to train local residents, and where tax revenues will be allocated. Perhaps the largest policy consideration will be manufacturing siting and domestic worker requirements. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory released estimates for job growth in the offshore wind sector to meet the US offshore wind targets by 2030. Manufacturing and supply chain are estimated to make up 85% of jobs in the sector. They are also the jobs that will likely be the most stable over time, as installation jobs will eventually end in the region as the nearest construction sites are completed. Domestic content requirements create a huge amount of uncertainty in the total American jobs as NREL estimates 15,000 jobs on 25% domestic content and 58,000 jobs based on 100% domestic content scenarios (Fig. 2). Balancing the benefits of domestic jobs with the benefits of accelerating our clean energy buildout by utilizing foreign offshore wind supply chains will be one of the most important political challenges in this sector. If a technical workforce cannot be trained to match the manufacturing and operations needs to meet our renewable energy goals we may lose out on both the jobs and the benefits of lower energy prices, reduced pollution, and new tax revenues to address current community priorities.