Underwater Wealth: The Life and Future of the Deep Sea

The abyssal zone lies 15,000 feet below the ocean surface and is a cold, dark place. Barring the occasional oceanic trench, this zone is the deepest part of the ocean and covers roughly 83% of the seafloor. Temperatures hover just above freezing, water pressure is 750 times greater than that at the surface, the last rays of sunlight fade out thousands of feet above, and oxygen is virtually nonexistent. The abyssal zone is a seemingly unforgiving and inhospitable place. But these conditions haven’t stopped a diversity of life forms from arising and thriving in this eldritch environment. The gummy squirrel, a species of sea cucumber, uses its large tail to hitch rides on deep ocean currents and feeds on phytoplankton that drift down from the surface. Meanwhile, the vampire squid, with the largest eye proportional to its body size of any animal and the slowest metabolism of all cephalopods, flits around the deep sea while feeding on detritus from above. As it turns out, a unique collection of animals all thrive in the abyssal zone, including fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and more.

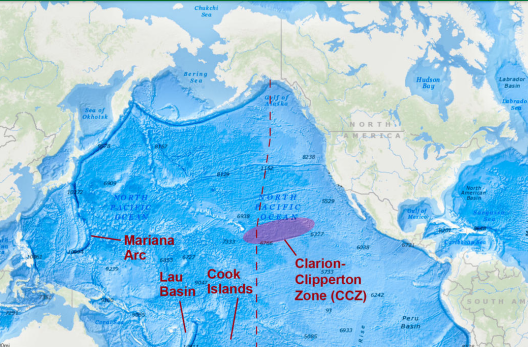

Despite constituting most of the Earth’s oceans, the deep sea remains largely unexplored. One area, however, has begun to garner more attention than others: the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ). This geological region east of the Hawaiian Islands in the Pacific Ocean encompasses roughly 1.7 million square miles of seabed and has been a hotspot for ocean exploration. A study published earlier this year summarized findings from recent scientific expeditions to the CCZ, revealing that over 5,500 unique animal species have been observed. Most of those animals (up to 92%) are completely new to science. And these are only the species that the expeditions found. Who knows what else still lurks in those depths?

The CCZ is important for another reason—it is home to the largest known field of polymetallic nodules on the planet. Polymetallic nodules are potato-sized conglomerations of minerals on the seafloor that contain manganese, nickel, copper, cobalt and other rare-earth elements (REEs). These nodules can take millions of years to form, and they provide a substrate on which deep sea organisms—like sponges and corals—can grow. The presence of these mineral-rich nodules make the CCZ a priority target for extraction via deep-sea mining. And demand for these minerals is only increasing.

This rise in mineral demand stems from climate change concerns. If we want to avert the worst impacts of climate change, we need to overcome our reliance on fossil fuels through electrification and a switch to renewable energies. This electrification, unfortunately, comes with a cost; batteries, wind turbines, and electric vehicles all demand greater amounts of minerals like cobalt and lithium. In fact, an onshore wind power facility requires nine times more minerals than a gas-fired plant. Advocates for deep-sea mining claim that the seabed is the best way to source these minerals. Opponents, however, are concerned about the detrimental impacts mining could have on these fragile and unknown ecosystems. Habitat destruction, creation of sediment plumes in the water column, noise and light pollution, and the production of toxic byproducts during mineral processing are all consequences of deep sea mining where the full impacts to ecosystems are still not well understood.

Mining of the deep seabed beyond 350 nautical miles from a nation’s coastline is regulated by the International Seabed Authority (ISA). Established in 1994 by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the ISA oversees the use and exploitation of all minerals and ocean floor resources outside of national jurisdiction—a region it has dubbed ‘the Area’. In its mission statement the ISA describes these resources as the “common heritage of mankind” and insists on the equitable distribution of wealth extracted from these resources to all nations. Currently, the ISA has only issued exploration contracts for mining of the seabed. 17 of the 30 contracts issued are for the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. As of this writing, there is no active mineral extraction of the seafloor taking place. Yet this is not a possibility reserved for the distant future.

In 2021, Nauru, a small island nation pillaged by colonial phosphate mining, submitted its intent to start deep sea mining in the CCZ, triggering the United Nation’s “two-year” rule. This essentially means the UN has two years to develop and finalize rules and regulations regarding deep sea mining. At the end of the two-year period, whatever rules are in place become final. That deadline passed in July of this year, and the ISA has still not finalized many environmental regulations. They are set to meet again this year, but any proposed rules would need to be approved by all 36 nations on the ISA’s council. With varying degrees of enthusiasm for deep-sea mining between member states, reaching a unanimous agreement seems unlikely, which will probably result in further delays. Nations are still not in agreement on how, when, or even if the deep sea should be mined.

Earlier this year, Canada joined a growing list of nations in support of a moratorium on deep sea mining in the Area until adequate regulations and protections can be developed. On the other hand, Norway has proposed opening parts of its continental shelf for mining of the seabed. China, too, with the most exploratory contracts of the seabed of any nation, is vying to be a world leader in the deep sea mining industry. Other pro-mining nations have made strides by sponsoring large multinational mining corporations. Nauru, for example, sponsors Nauru Ocean Resources, Inc., a subsidiary of The Metals Company, a Canadian based mining corporation. It is unclear as to whether or not the profit-seeking motives of companies like this will align with the ISA’s mission to protect the seabed, and how royalties collected by the agency from these companies’ revenues will impact the ISA’s ability to make unbiased regulatory decisions.

In the face of these uncertainties, land-based solutions may remain a more feasible alternative to sourcing minerals from the sea. A recent UN report found that 50 million tonnes of e-waste are produced globally each year–waste valued at around $62.5 billion. Only 20% of that waste is formally recycled. There is a literal goldmine of mineral wealth sitting in landfills around the world. Admittedly, isolating these elements from e-waste can be costly and requires sophisticated chemical and industrial processes. Efficient collection and recycling facilities still need to be developed before this can be seen as a reasonable alternative. But with significant private and public investment paired with government regulations and incentives to encourage the development of a circular lifespan for certain minerals, more progress can surely be made. While it may not completely replace the extraction of new minerals, this could at least reduce the stress on natural systems.

Developing a robust regulatory system to manage the seabed will be paramount in the coming years. As stated on its own website, The Metals Company—on behalf of Nauru—expects to begin commercial production in the CCZ as early as 2025. The impacts that deep sea mining will have on novel ecosystems on the seafloor—including organisms like the gummy squirrel and the vampire squid–are still not well understood. Nor is how much, if at all, deep sea mining would reduce the need for terrestrial mining—a claim often touted by supporters. What is certain, though, is that many questions remain. Until these questions can be answered with more confidence, a precautionary approach should be preferred until coastal states, the ISA, and all those with a stake in the seabed agree on a complete and transparent framework for deep sea mining.

Disclaimer: The regulations and status around deep sea mining are rapidly changing. After the first draft of this article was finished, the UK came out in support of a moratorium. Additionally, as of the date of this publication (11/1/23), the ISA is having its last meeting of 2023. Many more developments are likely to occur in the near future.