The Fight against Extraction: Civil Disobedience in the Climate Movement

On January 18 of this year, Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, who went by the name Tortuguita, was shot and killed by police outside of Atlanta. Terán was an environmental activist protesting the construction of a $90 million police training facility referred to by protesters as “Cop City.” This training center is slated to be built in a section of the South River forest – a large area of urban greenspace surrounded by predominantly Black communities. Concerned with the destruction of a forest and militarization of their local police force in a neighborhood that has disproportionately been victim to police violence, Terán and other activists have been staging a sit-in in the forest since 2021. While mostly nonviolent, some protestors have faced charges of domestic terrorism after destroying pieces of construction equipment. Their protests were inherently a form of civil disobedience, whereby residing in the forest – while technically illegal – they hoped to disrupt the construction of “Cop City” and bring wider attention to the issue. These forms of protests have been utilized in social movements throughout history to challenge the status quo and bring about meaningful change. Notably, civil disobedience has been employed by environmental activists and the climate movement to protest fossil fuel extraction by governments and corporations.

The term “civil disobedience” was popularized by Henry David Thoreau in his essay of the same name. A staunch opponent of the Mexican-American War and slavery, Thoreau protested what he viewed as unjust activities of the State by refusing to pay a poll tax – resulting in brief imprisonment. His decision to not pay this tax, while illegal, was nonviolent in nature and reflected his belief that by refusing to engage in certain institutions or to abide by certain laws, people could challenge the basis of these systems.

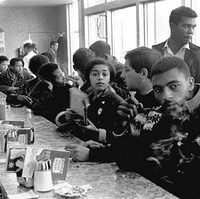

In the years since, Thoreau’s actions and ideas have influenced other activists, including Mahatma Gandhi and Rosa Parks, as they used methods of nonviolent civil disobedience in pursuit of their goals. Locally, Billy Frank Jr., a citizen of the Nisqually Tribe, was arrested over 50 times in the 1960s and 70s for “illegally” fishing in the traditional waters of his Tribe. Joined by other Tribal activists, he organized “fish in” protests that ultimately led to the passage of the Boldt Decision, upholding the Treaty rights of Indigenous people in Washington State to fish in their accustomed fishing grounds.

Environmental movements are rife with examples of civil disobedience like this, where individuals publicly and willfully break the law in order to protect natural resources. Probably one of the most well-known types of civil disobedience in environmental action is that of activists camping out in or tying themselves to trees to protest the development of an area. In recent years, movements have employed similar techniques in protesting the continued expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure as people around the world fight to stop the extractive industries that are fueling the climate crisis. This interactive map from the Environmental Justice Atlas highlights many of these resistance movements and the diverse coalitions of people organizing against extraction.

Ende Gelände is one such group in Germany that is using civil disobedience against coal infrastructure in the country and throughout Europe. In recent years they have brought together thousands of activists to occupy coal mines and infrastructure such as railways to demand that the country immediately phase out coal – the dirtiest of fossil fuels. In their action consensus they express their mission statement: “In view of the urgency of the climate crisis and in view of the developments of recent months, we consider it necessary and appropriate to go one step further: from public protest to civil disobedience.” They express their commitment to nonviolence by neither endangering people nor destroying infrastructure, but by simply occupying and blocking production. Even with public outcry and opposition like this, Germany is highly reliant on coal as an energy source and has increased its use in energy production in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In spite of this seemingly uphill battle, Ende Gelände continues to organize mass protests to oppose the burning of coal and is confident in the ultimate success of their efforts.

A more regional example of civil disobedience are the actions taken by people in Bellingham, Washington to successfully protest the development of the Gateway Pacific Terminal – a large coal shipping port – in 2011-12. Various efforts took place and used different approaches to oppose this project. One group attempted to pass a city ordinance to ban coal trains, an act that would have been illegal under federal and state law. Another smaller group of activists blocked and chained themselves to the train tracks until they were arrested by police. Stopped for hours, these BNSF freight trains would have been the very same ones to deliver coal to the proposed shipping terminal. Ultimately, it was a legal battle brought forward by the Lummi Nation that stopped the development of the terminal as it would have violated the Tribe’s fishing rights. Civil disobedience by the people of Bellingham may not have been the direct cause of the terminal project being abandoned, but these actions contributed to putting pressure on the government and bringing wider attention to the issue.

In addition to coal, pipelines for the transport of oil and natural gas are often a target by activists in the climate movement. In the Appalachian Mountains of western Virginia, a small group of activists protested the construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline – a natural gas pipeline – by camping out in trees that lie in the pathway of the pipeline project. A rotation of volunteers continually camped out in platforms built in the trees for three years, starting in 2018. In the spring of 2021, the final two tree-sitters were removed from the trees and arrested. While the pipeline is still on track to be completed by 2023, these protests delayed construction significantly and represent a larger social movement fighting back against dirty sources of fuel and energy.

The fight against construction of pipelines in general in the United States has had varying degrees of success. The Keystone XL pipeline permit was ultimately revoked by the Biden administration and the project essentially abandoned, but not until more than a thousand activists had been arrested at large sit-ins and massive protests created strong public opposition to the pipeline. On the other hand, protests at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline were unsuccessful as the pipeline began operating in 2017 (however, litigation continues with a new draft Environmental Impact Statement on a portion of the pipeline expected to be released soon). Regardless of their outcomes, nonviolent protests of this nature have been gaining more and more support as people grapple with the effects of climate change and stand up to the industries responsible. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has recently started tracking the size and number of climate protests in their Climate Protest Tracker. Since 2022 alone, they have tracked about 30 major protests around the world, nine of which were large protests of over 10,000 people.

Movements that incorporate civil disobedience may not always be successful. Oftentimes, civil disobedience alone is not enough to tip the scales. These actions are often paired with democratic processes, tireless legal work, and political advocacy that cumulatively pressure institutions to change regulations and behaviors. In fact, the radical flank effect is an observed phenomenon where radical actions, like civil disobedience, in a movement can help garner greater support for the more moderate factions of the same movement. The disruptive nature of civil disobedience brings issues into the spotlight while also having an immediate, tangible impact on the status quo operations of extractive industries and power of the State. These nonviolent methods are employed by individuals or groups of people to protest against laws, regulations, or other economic activities that they see as being unjust. They can serve as a signal to the wider public on the importance of certain social or environmental issues. People make a great sacrifice by doing something for a cause that could get them arrested, or in the case of Tortuguita Terán, killed, but the strength of such a commitment publicly highlights the passion they hold for the important issues being fought over. The climate crisis and environmental degradation threaten our very existence on the planet and by disrupting these processes through civil disobedience, some activists have been able to encourage a shift to more sustainable alternatives.