Food Sovereignty in the Arctic

In an age of climate change, Arctic Indigenous communities around the world are working to sustain their rich land and sea-based food traditions, while also navigating the inequalities of retail food markets[1]. Northern communities from Scandinavia and Russia, to Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, geographically remote communities throughout the Arctic often receive external groceries by air, ice road, sealift, or barge. For both the Iñupiat in Alaska and Inuit in Canada, the price of groceries in the Arctic are severely inflated, causing some households to choose between food and other essential items. Across North America, Arctic Indigenous communities must navigate the intersecting threats of food insecurity — grocery price gouging, and expanding challenges to local hunting practices from climate change.

According to this article written by Elyse Skura in 2016, grocery foods in Nunavut, Canada cost up to three times the Canadian average. In Jenn Ningiuk’s (@/jennningiuk4) video and Ky Flaherty’s (@/arcticmakeup) video in May 2021, product prices at their respective Nunavut grocery stores are shocking — $24.99 for 2 kg (4.4 lbs) of sugar, $16.89 for a can of soup, $12.49 for 295 mL for frozen juice, one liter (less than 0.3 gallon) of oil cost $14.69, bell peppers for $5.99 per kg (or per 2.2 lbs).[2] Similarly, this blog compares a standard lower-48 grocery store’s prices versus what the writers noticed in Utqiagvik, Alaska which included flour for $10.99, a half gallon of milk for $7.89, and a pack of 18 eggs for $5.99.

With the severity of climate change affecting the Arctic particularly hard, there has been increasing attention to issues of Arctic food security and food sovereignty within both popular discourse and policy spaces. While local, regional, and federal institutions recognize the complex interplay of both land- and market-based foods, they demonstrate a range of approaches to these questions in Arctic Indigenous communities.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, for example, defines food security as everyone having “physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.” In keeping with this perspective, federal and state governments in both the US and Canada have created programs that provide community-scale subsidies on foods or provide grants for food security. For example, the Canadian government provides subsidies for groceries through Nutrition North Canada, or NNC. Eligible communities can purchase subsidized foods from the eligible foods list, such as fresh, frozen, or dried fruits and vegetables, bread, milk, meats, and some other non-food grocery products. Along with federal programs (such as TANF and WIC) which are widely accessed in Arctic Alaska, Alaska’s Division of Agriculture provides a micro-grant for food security available for individuals and “qualified organizations” which was noted to have received an “overwhelming response.” Community and household scale subsidies are useful especially to buffer against food shortages, however, they are not enough to fulfill the rich cultural and social importance of food for those who live in the Arctic[3].

Kivalina, Alaska is a 500 person Iñupiaq community in Northwest Alaska, where many community members experience these challenges intimately. Reppi Swan is a whaling captain and president of the Kivalina Volunteer Search and Rescue. In conversation with the anthropologist P. Joshua Griffin, he stated that, as compared to caribou meat, store-bought meat “gets tiring…[and] it don’t fill our stomachs”. Similarly, Reppi’s sister Janet explained the need for food the community hunts because it is “very nutritious, whereas the Western style food is very fattening” and unfulfilling[4]. In Kivalina, as throughout the Arctic, community-hunted foods are both more beneficial for the people and provide a more-than-physical fullness through the connection with the land by hunting, and with the community by sharing with family and friends.

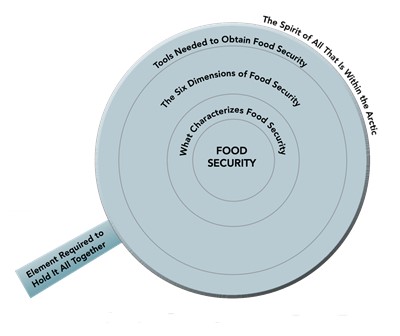

Likewise, many Indigenous-led organizations take a more holistic approach to building food security, grounded in the concept of “food sovereignty.”[5] The Inuit Circumpolar Council -Alaska, or ICC Alaska, defines Inuit food security as the right for people to access physically and spiritually nourishing food that comes from Inuit-managed land and is redistributed to the community. With this, it becomes abundantly clear that Inuit food sovereignty encompasses more than just a meal. In the ICC-AK full technical report, Inuit food security is conceptualized as an interconnected system with several layers. These different elements, as depicted in the photo below, make up the dimensions of food sovereignty that serve as a precondition to food security.

While NNC subsidies might ensure Inuit in the Canadian Arctic have groceries, they are still disproportionately at risk of obesity, chronic diseases, and mental and physical health issues (3). Food sovereignty is a framework to ensure not only that people have sustenance, but that food satisfies a cultural, social, and spiritual need as well. The value of hunting, fishing, and/or whaling practiced by Arctic Indigenous peoples transcends several boundaries — strengthening bonds from the ice between friends and relatives, to the homes where animal-skin clothing is made, to the kitchen tables where food is shared between people. This fosters a relationship of respect and reciprocity between communities, but also between humans and non-humans. Much of what is gained from hunting, fishing, and whaling trips is brought back to communities and distributed between families often by word of mouth, or through programs like community freezers[6], and much of the knowledge gained through these trips is grounded in personal, often intergenerational, relationships.

While the subsidies approach taken by the western government is valuable when facing food shortages and provide a variety of food options, such programs do not incorporate the multi-dimensional aspect of Arctic Indigenous food traditions as outlined in the ICC-AK Food Security report[7]. Indigenous-led institutions are guiding the way toward implementing policy and programs that move beyond these limitations. Approaches have been implemented to address food sovereignty, including the Elders Traditional Food Support Hunters Program, a Kotzebue-based program providing elders with niqipiaq (foods), Elders Meal and Transportation Program where meals are shared at Utuqqanaat Inaat in Kotzebue and at the local schools, and the Alaskan Inuit Food Sovereignty Management Action Plan which is a call to action from Alaskan Inuit and follows up on the ICC Wildlife Management Summit. Programs such as these address the multi-dimensional nature of food sovereignty in the Arctic. What is hunted within a community is then redistributed or shared, and is also supportive of other culturally and economically significant practices including artistic expression. For example, sealskin clothing from lawyer and artist, Aaju Peter, animal bone sculptures made from various artists, or sealskin jewelry from family businesses.

To maintain or establish greater food sovereignty in the Arctic, Inuit and Iñupiat also endure and are responding to the prejudice and racism of settler-dominated society. These can take many forms, including ridicule or hate from animal rights groups or activists charging forward in the name of conservation. This was the focus of director Alethea Arnaquq-Baril’s film Angry Inuk which raises attention to the hardships placed on Inuit communities based on deep-seeded misunderstanding of the Arctic practices such as seal hunting. Similarly, internet hate can run rampant as is evident in the comments on videos of community-harvested foods like Inuk Shina Nova’s (@/shinanova)’s on TikTok. But in the face of those challenges, the Inuit and Iñupiaq hunters, storytellers, artisans, and community members persist with pride. As an example, Nova is a throat singer, model, and content creator who proudly displays her cultural practices, which naturally includes foods. Arctic Indigenous peoples continue to face racism, discrimination, and censorship with courage and resilience through different mediums such as social media content, music, clothing, food, or film. Proudly uplifting and respecting this resilience is the first step in turning the tide.

Special thanks to Jenn Ningiuk and Ky Flaherty for allowing me to use their videos and providing feedback for this article, and to Griff, Reppi Swan, and Colleen Swan for the continued conversations and guidance on this topic via our discussions in our seminar course, Polar Science and Arctic Indigenous Communities.

[1] “The Retail Food Sector and Indigenous Peoples in High … – PubMed.” 27 Nov. 2020, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33261090/.

[2] Please note that these prices are in Canadian Dollar. Their respective prices in USD are: $19.89, $13.45, $9.94, $11.69, $4.77

[3] “Contemporary programs in support of traditional ways … – PubMed.” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25460908/.

[4] P. Joshua Griffin (2020) Pacing Climate Precarity: Food, Care and Sovereignty in Iñupiaq Alaska, Medical Anthropology, 39:4, 333-347, DOI: 10.1080/01459740.2019.1643854, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01459740.2019.1643854?journalCode=gmea20

[5] “Food Sovereignty. Revitalizing Indigenous Food Practices and ….” https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/5/3/57. See particularly page 10 of 14.

[6] Organ et al. 2014 define community freezers as a program or initiative where harvesters within the community supply wild food so others can access it, particularly redistributed to elders.

[7] “ALASKAN INUIT FOOD SECURITY CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK:.” https://iccalaska.org/wp-icc/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Food-Security-Full-Technical-Report.pdf. See pages 38-42.