Waterfront Ballard from 1900 to 2022: A Photo Essay

Last fall, I wrote an article for Currents about my hometown’s changing shoreline. This is its companion piece, a brief photo essay about Ballard, the neighborhood where I have lived in northwest Seattle during my second year at SMEA. I will take you through a few landmarks that have remained on Ballard’s waterfront over the last century, reminders of its history and how the neighborhood has been shaped by maritime activities.

Part of the homelands of the Duwamish Tribe for at least 12,000 years, Ballard began to be colonized by settlers in the 1850s. It was incorporated as its own town in 1890, then annexed by Seattle in 1906. The neighborhood’s lumber industry, including the world’s most substantial shingle manufacturing at the turn of the century, and its fishing fleet drew immigrants from Scandinavia in particular. Today, although you can go to Ballard just for the excellent breweries and restaurants, you can also easily find the neighborhood’s continuing connection to the water. In this essay I will focus extensively on the most obvious maritime landmark: the Ballard Locks. Now more than a century old, the Locks continue to be an important transportation hub for commercial and recreational vessels; their construction had a dramatic impact on both the landscape and people of Seattle.

Ballard (Chittenden) Locks

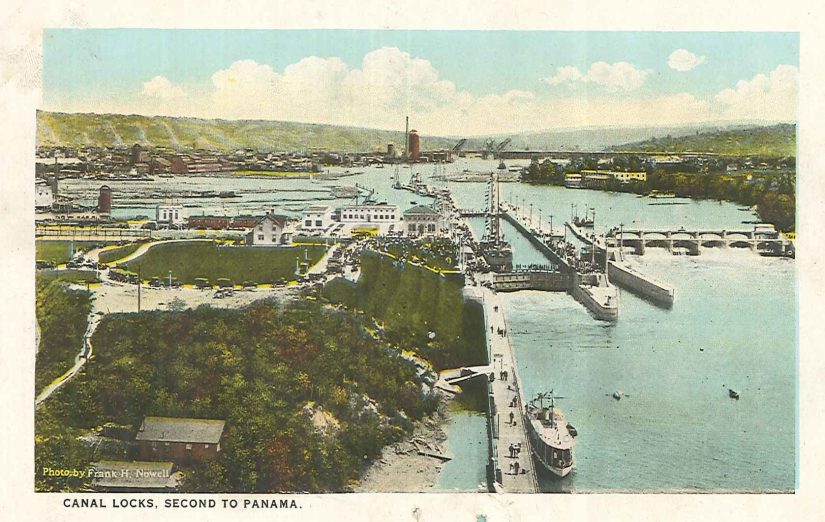

The Ballard Locks are one of Seattle’s most famous attractions. Locks move vessels between bodies of water at different heights, in this case connecting Lake Washington and Lake Union to the Puget Sound and Pacific Ocean via the Ship Canal. Annually, 40,000 vessels move through the Locks and 1.5 million visitors come to watch them “lock through.” Prior to the construction of the Ship Canal and the Locks, only little boats and logs for the lumber mills could navigate the small canals connecting Salmon Bay to Lake Union and Lake Washington. After its completion in 1916, the much-deeper Ship Canal allowed for passage of freight and shipping vessels.

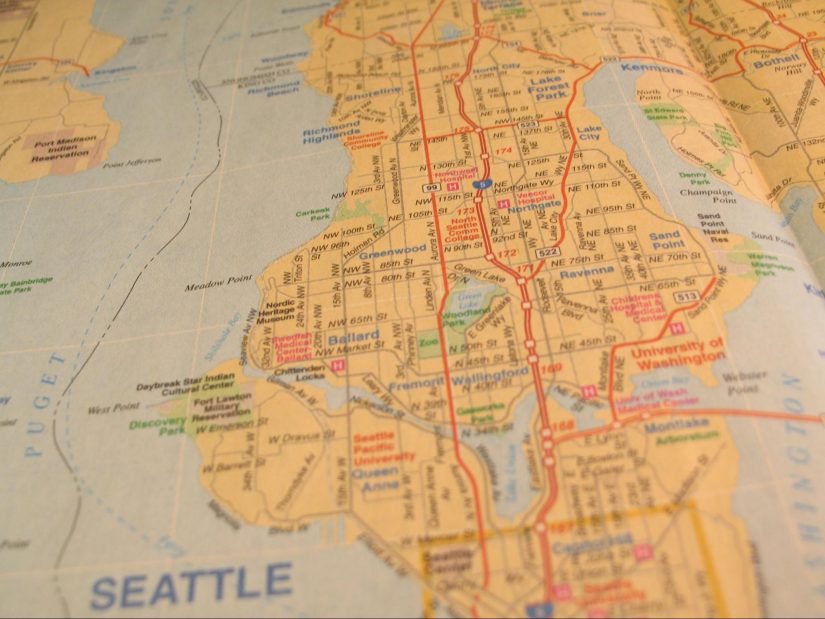

This graphic from The Seattle Times illustrates the sheer scale of the engineering required to construct the Ship Canal. The map also hints at the displacement of hundreds of Duwamish people that resulted. This displacement primarily occurred along the Black River: when the Canal was built, it dropped the levels of Lake Washington 9 feet, drying up the Black River, near Renton, that connected the Lake to the Duwamish River. Almost 300 members of the dxʷdɐwʔabʃ] (anglicized: Duwamish) Tribe lived along the Black River and relied on it for fishing.

The most obvious example of Indigenous displacement, due directly to the Locks themselves, was of Hwehlchtid, one of the last residents of sHulsHóól (“Tucked Away Inside”), a Duwamish village that is the namesake of Ballard’s Shilshole Bay. Hwelhlchtid and his partner, Chilohleet’sa, owned ten acres just across Salmon Bay from Ballard, in what is now the Magnolia neighborhood. In 1913, Hwehlchtid was evicted from his shoreline home in order to deepen the waterway, preparing it for ships passing through the Locks. By this time Chilohleet’sa had already passed away, and Hwehlchtid was taken by Bureau of Indian Affairs agents to the Suquamish Tribe’s Port Madison Indian Reservation.

For more information on 19th and early 20th century Indigenous history in Seattle, another helpful resource is Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place by Dr. Coll Thrush.

2018: Cecile Hansen, Chair of the Duwamish Tribe and enrolled member of the Suquamish Tribe, gives an overview of Duwamish history with settlers over the last almost two centuries. When describing her decision to pursue the position of Chair in the 1970s, she talks about her brother fishing in the traditional fishing areas of the Duwamish and getting cited by the WA Department of Fish and Wildlife. The Duwamish Tribe is still not federally recognized; this ongoing battle has recently been highlighted in a Seattle Times article. For more information, please visit the Duwamish Tribe website or the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center. Video courtesy of Seattle Live.

Ballard Bridge

The Ballard Locks have been a defining part of the neighborhood, and because of their pivotal role I have devoted a lot of time to them here; however, let us continue our walk now through the rest of the neighborhood.

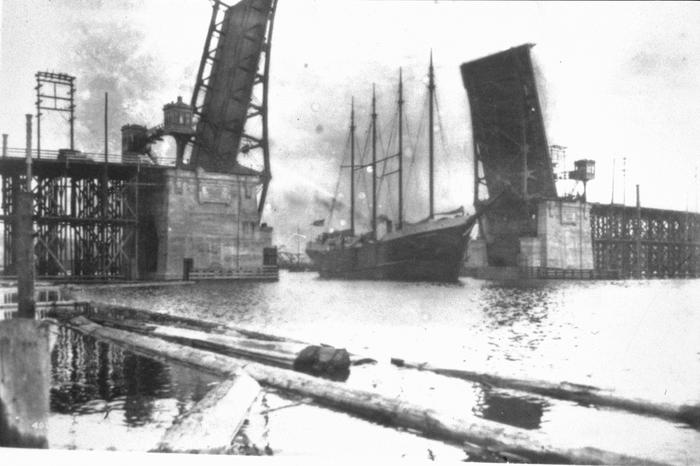

As someone who arrived in Seattle only recently, I am continuously amazed when I see a bridge raise for a ship. This phenomenon is visible with the Ballard Bridge, which splits in the center to allow passage of tall vessels. First built in 1917, shortly after the completion of the Locks, it stretches across the Ship Canal, connecting Ballard to Interbay. It continues to be a key part of Seattle daily transportation, even meriting its own parody Twitter account for frustrated commuters (although it remains down during peak rush hour). To request passage, vessels whistle, beginning a four-minute-long process of opening and closing the bridge. From 1937 to 1939, the original timber of the bridge was replaced with the steel and concrete we see today as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal.

2019: The Ballard Bridge raised for a sailboat. This version of the bridge is not the original, but the second version built in 1939. Video courtesy of fakeconsultant.

Ray’s Boathouse (Shilshole Bay)

Founded by Ray Lichtenberger as a bait house and boat rental near the Locks, Ray’s Boathouse has been a staple of the Seattle waterfront since 1939. In 1945 it added a cafe, and by 1952 featured the neon red sign still visible today. In 1973 it was converted into an upscale seafood restaurant, which was notable for being the first to feature native Olympia oysters after a decades-long hiatus from Seattle restaurants. It also bought fish directly from Seattle fishers as they came past. Nowadays, Ray’s still has a few contracts with Seattle fishing vessels, fishing in areas such as Alaska’s Copper River, but those fish are shipped in by air rather than by boat. Although the restaurant has burned down twice, it remains a fixture on the waterfront today.

Pacific Fishermen Incorporated (Salmon Bay)

One of my favorite maritime landmarks is the Pacific Fishermen Incorporated (known familiarly as PacFish). Founded in 1946 as a co-op shipyard by Norwegian Ballardites, it continues to service boats up to 300 feet in size and particularly fishing vessels. In recent years, Pacific Fishermen Shipyard has gained a reputation with the Port of Seattle as an eco-friendly establishment, having implemented solar panels, high efficiency boilers and air compressors, and stormwater filtration among other measures.

Fishing Fleet

As you cross the Ballard Bridge, you’ll see lots of fishing vessels beneath you at Fishermen’s Terminal (formerly Salmon Bay Terminal), located across the Ship Canal from Ballard in the Interbay neighborhood. What surprised me most about these vessels is that many of them will travel to the Alaska side of the Bering Sea to fish, returning at the end of the summer fishing season. In fact, the F/V Northwestern, the only vessel to have continued through all 17 seasons of the reality show “Deadliest Catch,” is docked at Fishermen’s Terminal. As the name of the show, which focuses on crab fishing in Alaska, implies, the profession is a dangerous one. Fishermen’s Terminal has 670 names on its memorial of fishers who have died at sea. Ballard’s First Lutheran Church has a long tradition, in response, of blessing the fleet every March at the beginning of halibut season.

2019: Fourth-generation Ballardite, Pete Knutson, talks about the life of a Seattle fisher. He sells fish during the winter straight off of his boat at Fishermen’s Terminal. Video courtesy of WhereByUs.

As I prepare to leave Seattle after graduation this summer, I feel lucky to have gotten the chance to explore this neighborhood. Its connection to the water permeates its art, architecture, and industry.