Maritime Manhattan From 1880 to 2021: A Photo Essay

At the 2021 Pacific Marine Expo I heard a poem describing a gradual loss of Seattle’s working waterfront. Home for the holidays in New York City, I wanted to give a visual description of a similar process that has happened here in Manhattan, located in Lenapehoking, the homeland of the Lenape people.

Throughout my childhood I could still see structural ghosts of a bustling maritime past on the Hudson River and East River. To tell their story, I have dived into photo archives (both New York Public Library and Library of Congress) and Flickr. I have also enlisted the help of my brother, Ben Carr, an architect with a better eye and a better phone camera than I, and my mother, Cristina Carr, who graciously lent me her phone for my own photography attempts. This photo essay is only a snippet of New York’s maritime history, a sample of convenience of structures and images that have left particular impressions on me.

December 2021 – An old sign by the Hudson River hints at former trade built around the maritime economy of Manhattan. Meier & Oelhaf Co. Inc. was in business at this location from 1920 to 1984, but the building itself is older – it has seen Manhattan’s waterfront evolve since 1884. In a fascinating recent study, demolition of another Lower Manhattan building revealed structural timber made from old growth forest, including trees that had started growing as far back as 1512. Photo credit: Gabriela Carr.

December 2021 – An old sign by the Hudson River hints at former trade built around the maritime economy of Manhattan. Meier & Oelhaf Co. Inc. was in business at this location from 1920 to 1984, but the building itself is older – it has seen Manhattan’s waterfront evolve since 1884. In a fascinating recent study, demolition of another Lower Manhattan building revealed structural timber made from old growth forest, including trees that had started growing as far back as 1512. Photo credit: Gabriela Carr.

Manhattan’s Major Waterways, From A Ferry Perspective

As an island, Manhattan is connected to New York City’s other boroughs and to New Jersey through an extensive network of tunnels and bridges. While most now cross the rivers via these methods, you can still take a ferry to traverse Manhattan’s waterways, just as you could in the 19th Century.

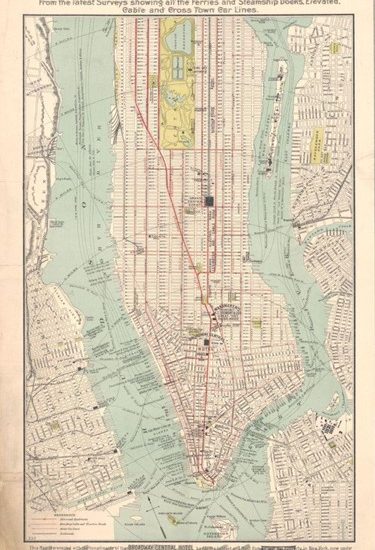

1890 – For those unfamiliar with Manhattan’s major waterways, the Hudson River runs along the west side of the borough, while the East River runs along the east side. In this map, Manhattan’s public transportation is shown as it looked more than a century ago, south of 96th Street. The lines on the Hudson and East River represent both ferry and steamship routes, visible with particular density at the southern tip of the island. Image credit: Broadway Central Hotel, available in the public domain.

January 2021 – Some ferry lines still carry passengers around Manhattan’s major waterways, over a century after the previous map was published. Image credit: The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, used with permission.

Ocean Travel from Steamships to Cruise Lines

New York City has welcomed ocean-going ships for centuries, as emphasized by the iconic Statue of Liberty. Over the last century, as planes have replaced ships for trans-Atlantic travel, the ships coming up the Hudson River, now fewer in number, have also changed.

December 1918 – Pier 54 on the West Side of Manhattan, just before the arrival of the RMS Mauretania bringing American troops home from Europe. The closest arch, just right of center, is Pier 54, with further pier entrances visible to the right. Photo credit: Bains News Service, available in the public domain.

December 2021 – With the era of the steamship long gone, the metal arch of Pier 54 is the only portion of it still standing today. Behind is Little Island, a popular new park built in place of the old pier. Photo credit: Gabriela Carr.

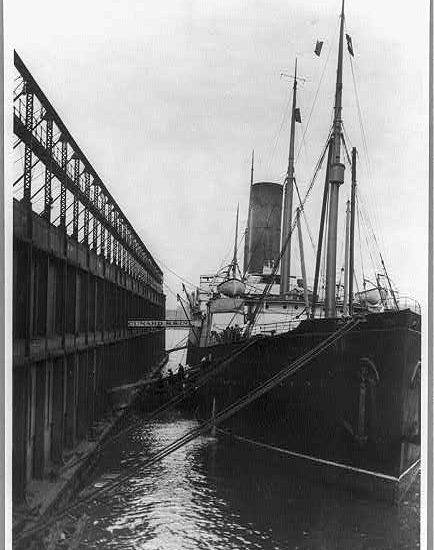

1912 – The RMS Carpathia, docked at Pier 54. This photo was taken the same year that the ship brought survivors of the RMS Titanic safely to New York. At the time Pier 54 was dedicated to Cunard Line ships, of which the Carpathia was one. The Titanic was meant to dock a few piers up, at the White Star Lines pier. However, although at the time the Cunard and White Star lines were separate companies, and rivals at that, today the remaining arch of Pier 54 still faintly bears the words “Cunard White Star.” The lines merged later in the century under pressure from the British government during World War II. This merger is a somewhat poignant coincidence in light of the relationship between the Carpathia and the Titanic. Photo credit: Unknown, available in the public domain.

March 2013 – Although planes have replaced ships as standard trans-Atlantic passenger transport, the West Side of Manhattan continues to host huge passenger vessels: cruise ships. The Cunard Line has a direct link to this industry – the company joined the Carnival Group in 1999. The Carnival Splendor in this photo is therefore, in some ways, a younger sister of the Carpathia, sailing along the same stretch of the Hudson River. Photo credit: Bob Jagendorf, some rights reserved.

The Last Remains of Cargo Shipping in Manhattan

Manhattan used to be not only a hub of passenger travel by water, but also a hub of cargo transport. The remains of some of this infrastructure are still visible, with a particularly striking example on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

1968 – Schematic of a transfer bridge in Baltimore, Maryland, a close match to one that operated on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Prior to the development of cargo containers for ships, railcars would be rolled along this bridge onto waiting barges. Controllers in the machinery house would raise and lower the bridge to match a barge’s height. Image credit: Historic American Engineering Record, available in the public domain.

September 1957 – New York Central Railroad’s railyard for its West Side Line. The Hudson River is visible in the background, on the west side of the railyard. The transfer bridge is just out of frame in this photograph, to the right. In 1985 the land was bought by Donald Trump; it is now the site of six Trump apartment towers. Photo credit: Angelo Rizzuto, available in the public domain.

December 2021 – The remains of the New York Central Railroad 69th Street Transfer Bridge. Built in 1911, it once could transfer 1000 tons of railcar onto barges in under 15 minutes, allowing cargo to move from the Upper West Side of Manhattan to New Jersey. Now, it is part of a park and protected under the National Registry of Historic Places. Photo credit: Ben Carr, used with permission.

Summer 2021 – Gantry cranes visible on the Brooklyn waterfront at Red Hook Terminal. The Financial District of Lower Manhattan can be seen in the background on the left. This is one of the few places in New York City, along with Staten Island, that serves container ships. Since 1921 the Ports of New York and New Jersey have been combined to increase cooperation. Ships are primarily unloaded in New Jersey, having moved away from densely urbanized parts of New York City to facilitate extensive land-based transportation. The Elizabeth-Port Authority Marine Terminal, part of this joint port, was the world’s first to serve container ships, beginning in 1962. Photo credit: Ben Carr, used with permission.

The Quieting Waterfront of the East Side

Although I am biased towards the Hudson River, as I grew up on the West Side, the East River has been a crucial part of Manhattan’s maritime history. Once bristling with masts as vessels filled the docks, the East River is now a quieter waterway, although still home to boats and fishers alike.

Mid-late 1880s – The packed docks of South Street Seaport, on the East Side of Lower Manhattan. The newly-completed Brooklyn Bridge is visible in the background. Photo credit: Unknown, available in the public domain.

Summer 2021 – Today’s East River waterfront, looking towards Brooklyn below the Brooklyn Bridge. Most traffic moved to the Hudson River in the beginning of the 20th Century, as the deeper Hudson can accommodate larger ships. However, some vessels do continue to travel along the East River. For example, in this photo a city ferry is visible in the background, while a motorboat is farther in the foreground. Photo credit: Ben Carr, used with permission.

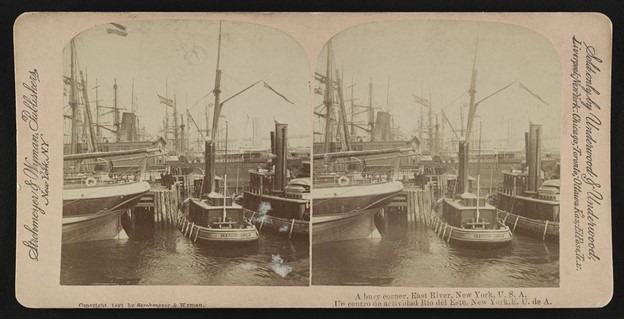

1905 – Stereograph of oyster and fishing boats docked on the East River. Oysters were once a staple of both Lenape and settler diets in this region. Nineteenth Century overharvest dramatically reduced the oyster population, but groups like the Billion Oyster Project have been working on restoration in recent years. Photo credit: Keystone View Company, available in the public domain.

May 2011 – A fisher on the East River, with the Brooklyn Bridge visible in the background. Fishing is permitted along both the East River and the Hudson River with a fishing license, subject to health advisories. Photo credit: Giulia Mulè, some rights reserved.

The Ever-Useful Tugboat

Like the ferry, tugboats have remained stubborn residents of Manhattan’s waterways to this day. Though small in size, they continue to play a large role on the two rivers.

1902 – Docked vessels in the East River, featuring two tugboats on the right. Photo credit: Strohmeyer & Wyman, available in the public domain.

December 2021 – The 1930 tugboat W.O. Decker, maintained and operated by the South Street Seaport Museum. The much-larger 1885 tall ship Wavertree looms over the tugboat to its left. As part of its mission to preserve the history of South Street Seaport and share this story with a wide audience, the Museum has restored several ships that are available for public tours. The barge used to hold ship restoration supplies is docked to the right in this photo. Photo credit: Ben Carr, used with permission.

June 2014 – A tugboat seen from the Lower West Side of Manhattan, travelling along the Hudson River. Tugboats continue to be used in both the Hudson River and the East River, often observed propelling barges. They even assisted in evacuations after the September 11th, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center. Photo credit: John Wisniewski, some rights reserved.

“Day’s End”: Connecting the Waterfront’s Past to its Present Through Art

I am certainly not the only New Yorker curious about the structural artifacts left behind from a busier time for Manhattan’s waterfront. Artist David Hammons has explored just such a topic, producing a piece that juxtaposes strikingly with the pilings left behind from steamship piers.

Winter 2020-2021 – The pilings of many steamship piers, such as these on Manhattan’s Lower West Side, have been left standing as parks are built on piers above and around them. These structures continue to serve as valuable habitat for marine life. Photo credit: Ben Carr, used with permission.

December 2021 – David Hammons’ 2014-2021 piece, “Day’s End,” recreates the outline of the warehouse that once stood on Pier 52. The installation points to a curiosity of present-day New Yorkers, such as Hammons himself, concerning the past of this changing waterfront and what once stood on those pilings. Photo credit: Gabriela Carr.

A surprising outcome of this project has been a realization that Manhattan’s maritime relationship with the water is not over, despite my childhood impressions. In a quieter way, each facet of waterfront activity covered here continues to operate in today’s Manhattan. The structural ghosts I remember from growing up are less lonely than I imagined.