Holding fast: How coalition building supports mobilization for kelp forest conservation in Puget Sound

As communities grapple with the concurrent and codependent effects of climate change and the degradation of marine ecosystems worldwide, the need for ecological conservation, restoration, and management has risen dramatically. In the last decade alone, nearshore ecosystems along the West Coast of North America have been hit hard by thermal anomalies, overfishing, and disease, among other local and global stressors. These disturbances are anything but benign, having led to substantial losses of numerous species critical to regional ecologies and economies. To address such complex challenges at the scale required, communities, governments, and organizations need to coordinate across sectors and across borders to enact policies and practices to sustain our vital ecosystems. Examining the case of kelp forest conservation in Washington’s Puget Sound, coalition building serves as a key tool for conservation mobilization.

The Pacific Northwest is synonymous with salmon, orcas, and Sitka Spruce. Often overlooked but equally important to life on this temperate coast is seaweed. These stringy, feathery, and encrusting macrophytes provide food and habitat to a diverse array of species, as well as supply important compounds for food, medicine, and technology. Of the hundreds of species of macroalgae that populate Washington’s waters, the bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) is among the most iconic. While most would consider seaweed a far cry from charismatic, bull kelp possesses a sort of ethereal beauty, with long blades that form vast canopies at the surface during summer months.

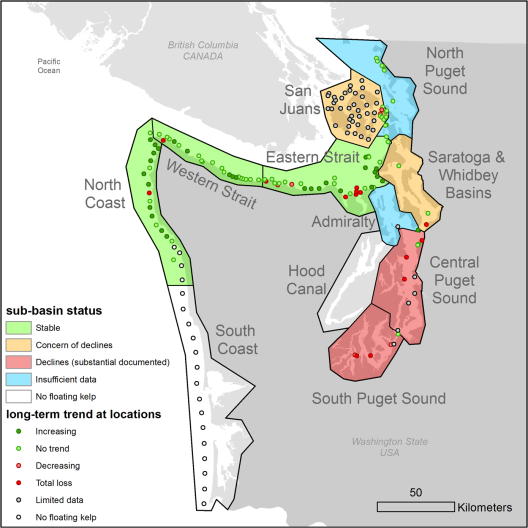

Bull kelp forests are foundational to the ecologies, economies, and communities of Puget Sound. This habitat-building species can host a diverse array of marine species and has an important role in nutrient cycling, facilitating the persistence of intricate food webs. Beyond its ecological functions, bull kelp is interwoven with histories up and down the west coast of North America. Puget Sound’s kelp forests have been declining over the past 150 years, exceeding global trends in kelp forest loss due to warming ocean temperatures and nutrient limitations. The reduction of available habitat and primary production associated with the loss of kelp has sweeping impacts on ecologically, economically, and culturally important species including salmon, herring, rockfish, and orcas.

Given the significance of bull kelp and the ecosystems it supports, a transdisciplinary coalition has formed to investigate the drivers of decline and pockets of persistence in Puget Sound. Emerging from the 2017 Rockfish Recovery Plan, the Washington State Kelp Research and Monitoring Workgroup consists of state, tribal, and non-governmental organizations with a vested interest in preserving and restoring thriving kelp forests. The consortium and its constituents have been making waves over the past several years. In 2020 the Puget Sound Kelp Conservation and Recovery Plan was published, documenting the status of kelp forests and making management recommendations for Central and South Puget Sound. Then, in a landmark example of bottom-up conservation action, the Washington State Legislature adopted SSSB 5619 in 2022, conserving and restoring kelp forests and eelgrass meadows in Washington state. The bill requires consultation and collaboration to “conserve and restore at least 10,000 acres of native kelp forests and eelgrass meadows” by 2040. Building on this momentum, several projects related to kelp forest monitoring and restoration have recently received funding as part of the Puget Sound National Estuary Program.

Collective action for conservation has created meaningful changes in policy and behavior. Take the case of the Elwha River dam removal on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. Through the advocacy of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and its allies, Congress passed the Elwha River Ecosystem and Restoration Act in 1992, leading to the eventual removal of the two dams in 2012 and 2014. The project’s success is evident in the restoration of the river’s natural flow, the recovery of salmon populations, and the revival of the ecosystem. Deemed the largest dam removal in U.S. history, this restoration project is a noteworthy example of collaborative action to restore both the environment and cultural heritage. Although conservation has notoriously been fraught with conflicting interests, limited scope, and short-sighted management decisions, working across disciplines may help foster greater innovation and inclusivity to make ecologically relevant and socially sustainable changes.

The kelp forest conservation effort has organically evolved around principles of inclusion, cohesion, and integration to build a sustainable movement and has demonstrated a commitment to these principles in three ways. First, by centering the expertise of various knowledge holders and sharing information horizontally between stakeholders, the coalition invites individuals and groups with varying perspectives to co-create action plans and gather the best available information. Second, the consortium enables monitoring over relevant spatial and temporal scales by developing consistent protocols and pooling resources, such as knowledge, funding, and access. Finally, by taking an ecosystem-based management approach that considers the estuarine system holistically, the movement ties into other conservation efforts, effectively building momentum and gaining visibility in front of decision-makers. These general principles readily translate to other marine and terrestrial ecosystems to advance conservation outcomes.

While the case for kelp should be shared and celebrated, knowledge gaps remain. Although it appears that mobilizing kelp conservation in Puget Sound is an exceptional demonstration of collective action, it may be too early to tell if it is leading to greater conservation success. Even though milestones have been achieved through legislative action and funding, it is too soon for the consortium to quantify the results of their collaboration in acres of kelp forest conserved or restored.

The burgeoning kelp forest conservation movement will not stop after these early successes. There is still a long road to enacting conservation and restoration measures on the scale required. As a local resident, there are several ways you can get involved. Firstly, you can educate yourself and others about seaweed harvesting guidelines and the value of kelp forests to nearshore ecosystems. Secondly, you can stay in the know by participating in the quarterly Washington State Kelp Research and Monitoring Workgroup meetings. Thirdly, you can contribute to monitoring efforts by participating in volunteer kayak surveys with the Northwest Straits Commission, SCUBA surveys with Reef Check, or one of the working groups within the international Kelp Node. Finally, you can adopt the guiding principles of inclusion, cohesion, and integration in your own management projects and conversations around conservation.

Kelp is a sentinel for ocean health. Not only can we learn from bull kelp’s resilience, but also from the way people are organizing around this foundational species to help a vital ecosystem persist within a changing ocean. While the future of bull kelp in Puget Sound remains uncertain, it is clear that this community is ready to collaborate and innovate to give kelp forests a fighting chance at recovery.