Big bad wolf and other tales: How psychology shapes our perceptions of wildlife

People tend to consider themselves rational beings, carefully analyzing new information to make conscious, informed, and logical decisions. However, the science tells us that we are anything but rational. Human decision-making relies on a great many mental shortcuts, pulls from personal experience and societal norms, moderates between established values and malleable behaviors, and makes compromises to compensate for a lack of information. These dynamics play a key role in shaping environmental management decisions. With the growing realization that biological dimensions of wildlife management are not the only drivers of successful population restoration or protection, social scientists are increasingly brought into conversations to help inform decisions about wildlife conservation.

One discipline that seeks to understand human-wildlife relationships is conservation psychology, defined by the American Psychological Association as “the scientific study of the reciprocal relationships between humans and the rest of nature, with the goal of encouraging conservation of the natural world.” A growing body of research in this field has investigated how human perceptions can interact with value appraisals and risk assessments of wildlife. This article examines the psychological processes that influence our perceptions, the disparity that can occur between knowledge and attitudes, and how these mechanisms ultimately influence decision-making.

The following takes a Western science perspective, within which most institutional psychological research is embedded. Western psychology paradigms tend to emphasize the individual, while non-Western knowledge systems often view human cognition as relational and deeply rooted in the surrounding world. These frameworks play a key role in how we understand human behavior, and are an important caveat to keep in mind.

The Cognitive Landscape – Values, Attitudes, and Behaviors

Human cognition refers to mental processes such as memory, decision-making, problem-solving, language, and learning. Each of these mechanisms can have important implications for wildlife management by providing a basis for understanding how humans might respond to environmental conservation efforts.

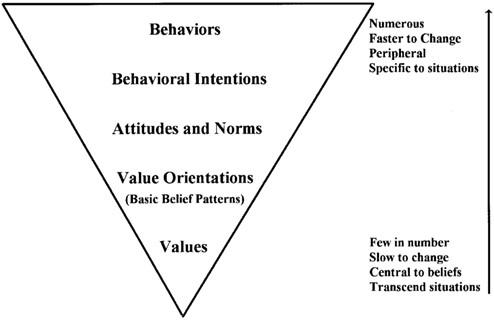

Social scientists Dr. Jerry Vaske and Dr. Michael Manfedo have applied a cognitive approach to wildlife management regarding how human thought processes shape behavior. This framework envisions how values form an individual’s attitudes and norms, which leads to behaviors. Values are abstract assessments of what one deems important in life; they tend to be formed during one’s upbringing and shaped by social networks. They are also few in number, slow to change, and core to one’s beliefs. Values influence one’s attitudes about policies or current events. For instance, a person who has one set of values, such as compassion or generosity, might be more prone to a mutualistic orientation towards wildlife, believing that wildlife have inherent rights. In contrast, a person with a different set of values, such as personal autonomy or self-reliance, may have a utilitarian orientation towards wildlife, believing that human needs have priority over wildlife wellbeing. These attitudes are very likely to shape behaviors including voting, environmental action-taking, and responses to wildlife encounters.

Two Systems of Thinking – Intuitive (Automatic) vs Analytical (Intentional)

An important theory in understanding how humans interpret information and make decisions are the two systems of thinking. System 1 is fast and intuitive, and System 2 is slow, pulling from analytical thought and logic. Both systems are constantly at work during waking hours: rational thought (System 2) hums in the background and kicks in during complex tasks and intentional concentration. Intuitive thought (System 1) rapid fires with automatic responses and informs System 2. Where intuitive thought is involuntary, rational thought is intentional. Both systems are always available to us and play important roles, but System 2 might only be summoned when System 1 stumbles, which means we often rely on mental shortcuts. The instantaneous thinking of our intuitive system cannot be shut off, but it can be moderated by System 2 (and practice can make us more in tune with our analytical thinking mode).

Faulty Rationality – Mental Shortcuts

Mental shortcuts known as heuristics or biases, operating in System 1 thinking, help us navigate our complex and stimuli-laden reality. However, they can also lead to cognitive errors such as inaccurately assessing the likelihood or risk of an event or encounter, which can shape human perceptions of wildlife. These types of thinking can be formed by societal norms, storytelling, or recalling an emotionally salient event. The following section will provide several examples of mental shortcuts.

The availability heuristic refers to the human tendency to assume that immediate mental responses are accurate representations of a situation or concept. A classic example of the availability heuristic is the common fear of flying despite the much higher statistical likelihood of injury in a car accident. Strong emotions can also lead to use of the availability heuristic. An example of this within a wildlife context is how the film Jaws “excited and terrified” viewers, ultimately shaping people’s perception of sharks. This film has been linked to an increased fear of shark attacks despite the high improbability of such an encounter.

Anchoring bias occurs when someone relies on the first piece of information they receive, and does not accurately update their perception before making a decision. An example of anchoring bias can be demonstrated with willingness to pay: a car salesman may initially show shoppers an expensive vehicle before a more reasonably priced option, anchoring shoppers to the expensive cost and creating the illusion that they are saving. This bias can be immediate. It also persists over the long-term in a process called self-herding, where an initial encounter with an object or experience, arbitrary as it may be, can lead to replicated behaviors and eventually the establishment of preferences. Anchoring can impact decision-making, and can help explain why societal discourse or folklore shapes risk perception of wildlife – particularly with species that are not regularly visible to us.

As a final example, confirmation bias occurs when people notice or unconsciously seek information that supports their existing beliefs, and can also have an important role in human-wildlife interactions. This bias plays out in many ways in our daily lives, such as in the news programming that we choose to watch. In the context of wildlife management, we can expect to see conservationists with an interest in restoring cougar populations consulting resources that speak to ecosystem health increases from apex predators. In contrast, ranchers who make their living off livestock may oppose such restoration and pay particular attention to news stories that report increased cougar sightings near farmland.

A great many cognitive biases shape human perception. These mental shortcuts help illustrate that rational thought, careful consideration of facts, and a dutiful reliance on knowledge are not actually the mental processes at play in many decision-making scenarios. They can also help us understand how wildlife value orientations are established and why some may feel great fondness for one species, while others will experience disgust or terror. Being aware of such mental processes is important for moderating overinflated risk assessment and fear response, and can also illuminate the ways in which affinity towards wildlife can hinder equitable and effective conservation efforts.

Wolves – A Case Study of a Vilified Species

While mammals are generally more accepted by humans than other organisms, the wolf is a notable exception. For centuries, gray wolves have been villainized and populations have been exterminated to near extinction. Prior to European arrival to North America, Indigenous communities respected the wolf and wove the animals into their folklore with reverence. When settlers arrived, bringing with them livestock deemed valuable for colonial establishment, wolves were perceived as threatening and promptly identified as an enemy. European settlers created stories about the wolf that presented a vicious and murderous creature, and pervasive eradication began. It is estimated that the North American wolf, once abundantly present throughout the continent, has been eliminated from over 90% of their historical range.

Following decades of widespread extermination of the species, wolves were listed on the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1974. As wolves were reintroduced to ecosystems in the West where they once played a key role, contentious battles between conservationists and livestock owners ensued. In 2020 the Trump Administration delisted the gray wolf from the ESA and returned management of the species to individual states. Intensive slaughters began immediately after removal from the ESA, fueled by inaccurate perceptions of wolf risk assessment. This led to the recent decision, in February 2022, to relist gray wolves on the ESA for federal protection.

Human attitudes based on erroneous beliefs about wolves are an important example of how perceptions can drive wildlife population depletion and recovery, and how these perceptions ultimately shape ecosystem health. While wolves have occasionally interacted with livestock, the frequency of such risk has been tremendously overinflated in Western discourse, leading to use of faulty biases and lack of rational decision-making. On the contrary, killing wolves has been linked to increased livestock attacks due to destabilizing pack dynamics. When looking at the statistics, one might actually be surprised that large predators don’t interact more frequently with domestic animals due to increased habitat fragmentation and human settlements encroaching on wildlife corridors. Wolves and other apex predators want to avoid human settlements, and that is generally what they do. The essential role that apex predators play in ecosystem function cannot be overstated, and legislation that ignores this fact due to inaccurate risk assessment perpetuates ecosystem degradation and biodiversity losses.

“The essential role that apex predators play in ecosystem function cannot be overstated, and legislation that ignores this fact due to inaccurate risk assessment perpetuates ecosystem degradation and biodiversity losses .”

Implications for Wildlife Management

Western society has historically considered humans distinct from biodiversity, a problematic view that has led to myriad threats to non-human beings via erroneous cognition. In previous centuries, whales were villainized or classified as fish by European settlers in North America, which helped justify culling efforts and the pervasive whaling industry. Despite their crucial role as ecosystem engineers, shark conservation efforts have been stunted by the fearsome image commonly portrayed by the media. The reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone continues to bring controversy despite the data that tells us they pose a comparable (and minimal) threat as other apex predators. Research has demonstrated that people have less interest in plant conservation than animals due to their faceless form. And experts have drawn a relationship between the perceived cuteness or anthropomorphic qualities of an animal and humans’ interest in conserving them.

The charismatic megafauna of the world are indeed important for functioning trophic systems and biodiversity, but the “creepy,” crawly, or perceivably fearsome species are integral to healthy ecosystems as well. How do we build compassion for the snaggle-toothed and snarling creatures who help create intricate balances that are vital for the existence of the perceived wildlife darlings? Conservation psychology can help wildlife professionals understand how humans make decisions by bridging the gap between knowledge and attitudes. This approach will support more effective wildlife management, where appraisal of a species’ value is not vulnerable to faulty reasoning, nor contingent on how they make us feel.

Contact Currents Editor-in-Chief for access to the following articles:

Czech, B., Krausman, P.R., & Borkhataria, R.R. (1998). Social Construction, Political Power, and the Allocation of Benefits to Endangered Species. Conservation Biology, 12.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world?. The Behavioral and brain sciences, 33(2-3), 61–135.

Ingle, M. (2021). Western Individualism and Psychotherapy: Exploring the Edges of Ecological Being. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 61(6), 925–938.

Macdonald, E. A., Burnham, D., Hinks, A. E., Dickman, A. J., Malhi, Y., & Macdonald, D. W. (2015). Conservation inequality and the charismatic cat: Felis felicis. Global Ecology and Conservation, 3.