At a terning point? The precipitous decline of the Pacific Flyway Caspian tern population

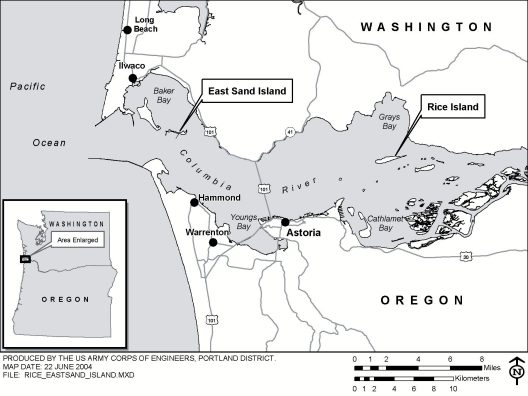

It’s a summer day near the mouth of the Columbia River in 1998. A cacophony of loud overlapping calls that sound like rusty see-saws dominate the bright afternoon. Interspersed between the louder calls are high-pitched whistles and peeps: Caspian tern chicks, begging for food. Small, grey, baseball-sized balls of fluff with bright orange bills, some nestling in underneath the wings of a parent, some vigorously running around the sandy colony pumping tiny, useless wings. The Rice Island colony is over seventeen thousand strong. Adult Caspian terns, with their brooding black caps, distinctive red bills, and arching graceful wings, come and go, some bringing small fish—fresh from the Columbia River—for their chicks. They’ve been migrating to this site, the largest Caspian tern breeding colony in the world, from southern California, Mexico, and Guatemala for over a decade. In a few months, the adults and chicks will begin their return journey south for the winter. Next year, they will return to a changed island, no longer suitable for rearing chicks: sharp stakes protruding from the ground, fencing, and vegetation. For the next twenty years, they will be unknowingly caught in a one-sided arms race as resource managers struggle to control their population in a determined effort to protect salmon.

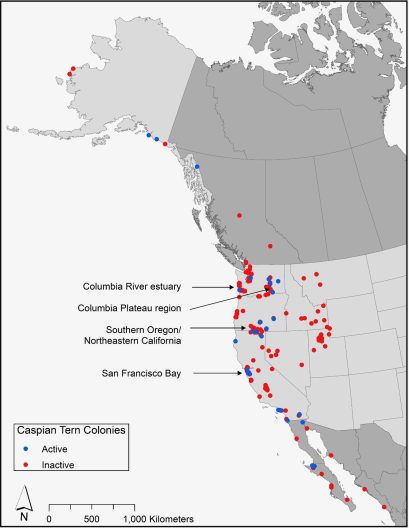

There wasn’t always such a large population of Caspian terns breeding in the Columbia River Basin. Before the large-scale loss of inland wetlands in the early 1900s that drove Caspian tern populations coastally and northward, breeding colonies in the Pacific Northwest were likely smaller and more geographically distributed. In the 1960s, the Army Corps of Engineers dumped massive amounts of dredging material into the Columbia River to create Rice Island, setting off the chain reaction that would haunt the agency for decades. By the 1980s, drawn to the relatively predator free area and the plentiful juvenile salmon and trout released from upstream hatcheries, terns established a breeding colony on Rice. Over the next twenty years, as the Pacific Flyway tern population more than doubled, Rice Island attracted terns like a magnet. By the early 2000s, Rice Island hosted around 60% of the Pacific Flyway population.

This created a thorny problem for tribal and federal resource managers. In 1998, the booming tern population consumed between nine and 15 million salmon smolt during the breeding season. Unfortunately, unlike the terns, salmon populations in the Columbia River Basin had plummeted. Twelve populations of salmonids in the Columbia River Basin were federally listed as threatened or endangered, and four stocks had already gone extinct. Before the 1850’s the Columbia River Basin produced the most salmon and steelhead in the world, with up to 16 million fish returning to spawn annually. Dams, upstream habitat loss, and overharvesting led to these historic runs declining to less than 10% of their original levels. With such depressed populations, managers needed to consider all sources of salmonid mortality, including those occurring during early life stages. In 1998 Caspian terns consumed a staggering 13% of steelhead smolts that reached the estuary. That same year, representatives from federal and state agencies, Tribal governments, and researchers created the Caspian Tern Working Group to discuss management options that would decrease tern predation on juvenile salmonids without jeopardizing the health of the tern population.

The first step was understanding if Caspian terns could be naturally relocated. Terns are opportunistic feeders, and relocating them downstream to East Sand Island, an artificial dredge island near the mouth of the Columbia, could potentially result in their diet shifting away from juvenile salmonids towards other fish species. And so, when terns returned to nest on Rice Island in 1999, they were met with a purposely inhospitable landscape. East Sand Island, in contrast, had what appeared to be a thriving population of terns already nesting—hundreds of wooden decoys and microphones playing tern mating and nesting calls. By 2001, the entire colony had moved to East Sand Island. The pilot project was a monumental success; tern populations remained stable between 2000 and 2008, but the percentage of their diet composed of salmonids fell from over 70% to just over 30%.

Unfortunately, even with this decrease, terns still consumed around five and a half million juvenile salmonids annually. In 2005 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published the Caspian tern management plan. Managers planned to use the same methods that succeeded at Rice Island to redistribute the Caspian terns on East Sand Island to seven alternative sites in Washington, Oregon, and California, far from the Columbia River Basin. The number of terns nesting at East Sand Island would be reduced by at least 60% to between 3,125 and 4,375 nesting pairs. NOAA Fisheries estimated that this reduction would result in three federally listed steelhead stocks growing by 1% or greater annually. Implementation of the plan began in 2008. As managers created theoretical tern habitat at alternative sites, they shrank the suitable habitat available at East Sand Island.

The East Sand tern colony reached its target size in 2017. By 2019, the colony consumed fewer than three million smolts annually, and by 2023, terns predated on less than 2% of smolts from each listed salmonid population. These were important milestones targeted in the management plan. Although the plan aimed to reach these goals without impacting the size of the Caspian tern population, unfortunately, during this same time period the Pacific Flyway population lost over half its members. The alternative nesting locations were plagued by drought, predation, and vegetation encroachment and three of them ultimately failed. On average, alternative sites supported 870 breeding pairs annually, far fewer than the thousands managers had hoped they would.

“Since the implementation of the management plan, the Pacific Flyway population of Caspian terns has lost over half its members.”

The previously vibrant colony at East Sand Island also faced unanticipated challenges. The colony was plagued by disturbances from bald eagles that led to adult terns chaotically fleeing the nest, leaving chicks and eggs behind to be voraciously consumed by opportunistic gulls. In six of the eight years between 2016 and 2023, complete nesting failure occurred and no tern chicks survived the island. In an ironic turn of events, some terns from East Sand Island began nesting further upstream on the Columbia, where their per capita predation rates on salmonids were significantly higher than at East Sand Island.

In 2021, fewer breeding pairs returned to East Sand Island than the minimum number set under the Caspian tern management plan. This should have triggered management actions aimed at reversing the decline in tern populations. Despite this trigger, in 2022 and 2023 managers failed to increase available nesting habitat for terns on East Sand Island. Instead, they conducted hazing to prevent terns from nesting outside their designated one acre area. Managers also prevented over a thousand terns from re-establishing a colony at their original location on Rice Island. Hazing activities included adding stakes with ropes and flagging to discourage nesting, walking through the site, using automated lasers to disrupt the birds, and collecting tern eggs.

In 2023 just 524 pairs of Caspian terns nested on East Sand Island and no fledglings survived. The former largest tern colony in the world, 10,700 nesting pairs, reduced by 95%. Then, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) struck the already declining population. At Rat Island, a colony of around 1,800 adults near Port Townsend, and the only remaining Caspian tern colony in the Salish Sea, over 1,000 adults and 500 chicks died. Dead terns washed up on the shores of the lower Columbia, and an epidemiological study estimated that an additional 10-14% of the entire Pacific Flyway population was lost to HPAI. This loss has accelerated the already rapid decline of the Caspian tern population.

The ethics of repeatedly disturbing or reducing the population of one species to benefit a more threatened species are complex. On the one hand, it seems straightforward: four of 16 salmon stocks in the Columbia and Snake rivers are extinct, and seven of the 12 remaining are federally threatened or endangered. They have tremendous cultural and ecological importance. Caspian terns have a worldwide range, and although their population has recently declined in the Pacific, they do not currently face the same extinction risk as the salmonids in the Columbia. If predation on listed salmonids can be decreased with minimal impacts to tern populations, that is an obvious win-win.

On the other hand, although Caspian terns feed on juvenile fish, the population of lower Columbia River steelhead is not threatened because of terns. They are threatened because upstream habitat is blocked due to dams and culverts, because of overharvesting, declines in genetic diversity due to hatchery-raised fish, rising stream temperatures, habitat degradation, and more. Unfortunately, the changes to the river that would address the root cause of the problem are also the most expensive, politically fraught, and complex: dam removal. Management of Caspian terns is an easily quantifiable, rapidly deployable band-aid that resource managers can apply to the gaping wound of an altered ecosystem. Are the terns just a distraction from the larger problem at hand? One could argue that the vast resources spent on tern management may have been better spent by investing directly in salmon restoration projects like culvert and dam removal, restoration of upstream habitat, and hatchery improvements.

If current patterns continue, the future of Caspian terns in the Pacific Flyway is bleak. With minimal suitable habitat available outside of the Columbia River Basin, measures discouraging nesting occurring inside the Columbia River Basin, and continued risks from highly pathogenic avian influenza, it’s hard to see how tern populations will recover without a major course correction. However, the tern management plan was designed to allow for adaptive responses to changing conditions and there are still options on the table.

“With minimal suitable habitat available outside of the Columbia River Basin, measures discouraging nesting occurring inside the Columbia River Basin, and continued risks from highly pathogenic avian influenza, it’s hard to see how tern populations will recover.”

Based on decades of their research on Caspian tern populations in the Columbia River Basin, scientists from Real Time Research and Oregon State University recently recommended three management actions; temporarily increasing the amount of nesting habitat available on East Sand Island, implementing limited lethal control on gulls to reduce tern chick predation, and establishing a new tern colony site along the Washington coast. Proposed locations for a tern colony included Grays Harbor, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and Puget Sound. Unlike the original alternative colonies, these areas are not as susceptible to drought and declines in forage fish availability, and are areas where terns have historically bred. When given the space, Caspian terns have shown that they can establish successful breeding colonies even in unlikely places like rooftops or barges. In Seattle, a colony of over a thousand terns used to nest on the rooftop of an abandoned factory near the Duwamish River, before the building was demolished.

Managers will have to act quickly—the Pacific Flyway population today is less than a third its size than in 2008. By creating new alternative tern nesting sites, expanding nesting area on East Sand Island, and controlling gull predation, managers can give the tern population a chance to recover, while still protecting salmon. And perhaps one day, the raucous cries of thriving tern colonies will once again echo across Washington’s coastline, and this time, in places where they are welcome to stay.

The following sources were used and are behind a paywall. Please reach out to the Currents Editor-in-Chief for access:

[1] Anderson, S. K., Roby, D. D., Lyons, D. E., & Collis, K. (2005). Factors Affecting Chick Provisioning by Caspian Terns Nesting in the Columbia River Estuary. Waterbirds, 28(1), 95–105.

[2] Collis, K., & Roby, D. (n.d.). Build it and they will come: Implementation of the Caspian Tern Management Plan. Retrieved February 8, 2025.

[3] Collis, K., Roby, D. D., Evans, A. F., Lawes, T. J., & Lyons, D. E. (2024). Caspian Tern Management to Increase Survival of Juvenile Salmonids in the Columbia River Basin: Progress and Adaptive Management Considerations. Fisheries, 49(2), 71–84.

[4] Collis, K., Roby, D., & Thompson, C. (2002). Barges as temporary breeding sites for Caspian terns: Assessing potential sites for colony restoration. Wildlife Society Bulletin.

[5] Craig, D. P., & Suryan, R. (2004). Redistribution and growth of the Caspian tern Population in the Pacific Coast region of North America, 1981-2000. The Condor.

[6] Evans, A., Collis, K., Banet, N., Payton, Q., Kobernuss, R., Windels, N., Peck-Richardson, A., Kennerley, W., Piggot, A., & Orben, R. (2024). Avian Prediation in the Columbia River Basin: 2023 Final Annual Report. Real Time Research, Oregon State University.

[7] Haman, K. H., Pearson, S. F., Brown, J., Frisbie, L. A., Penhallegon, S., Falghoush, A. M., Wolking, R. M., Torrevillas, B. K., Taylor, K. R., Snekvik, K. R., Tanedo, S. A., Keren, I. N., Ashley, E. A., Clark, C. T., Lambourn, D. M., Eckstrand, C. D., Edmonds, S. E., Rovani-Rhoades, E. R., Oltean, H., … Waltzek, T. B. (2024). A comprehensive epidemiological approach documenting an outbreak of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus clade 2.3.4.4b among gulls, terns, and harbor seals in the Northeastern Pacific. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 11.

[8] Roby, D. D., Collis, K., Lyons, D. E., Craig, D. P., Adkins, J. Y., Myers, A. M., & Suryan, R. M. (2002). Effects of Colony Relocation on Diet and Productivity of Caspian Terns. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 66(3), 662.

[9] Suzuki, Y., J. Heinrichs, D. E. Lyons, D. D. Roby, and N. Schumaker. 2018. Modeling the Pacific Flyway population of Caspian terns to investigate current population dynamics and evaluate future management options. Final Report submitted to Bonneville Power Administration and Northwest Power and Conservation Council, Portland, Oregon.