The long and winding road: charting the course of American conservation

Every Thursday through April and May, Currents is covering the past, present, and future of the conservation movement in the U.S. and beyond. This is the first article in the series, so stay tuned in the coming weeks for more!

By Dave Berndtson

For many, the birth of the movement to protect or sustainably interact with the natural world in the United States evokes images of leaders like Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir taking in the beauty of Yosemite from a mountaintop, or reflection of the exaltation of nature and simple living in Henry David Thoreau’s transcendentalist writings in Walden. These romanticized visions that embody the core of the American conservation movement to some, though, are only small portions of a much larger story. The movement’s journey in this country is complicated, filled with ups and downs and conflicting visions between conservation and preservation. It begins long before European settlers ever set foot on the East Coast. To tell the true history of the conservation movement on the lands we now call home, it is essential to talk about the contributions from those whose lands we brutally stole: Native Americans.

Native Americans, long before Thoreau wrote about his time in the woods, understood the importance of keeping the Earth healthy enough to provide for future generations. Natives established stewardship practices like controlled burning of forest understory and hunting and fishing long before European settlers arrived. Strong spiritual and cultural connections to Mother Earth and Father Sky, guided interactions with the world around them towards wise use of resources and respect for all living beings. Noted American conservationist George Bird Grinnell (who fought for the protection of bison and spent a lot of time learning from Natives) highlighted Native importance to informing his own conservation ethos: “He read the signs of the earth and the sky, and the movements of birds and animals, knew what these things meant, and governed his acts by what these signs told him.”

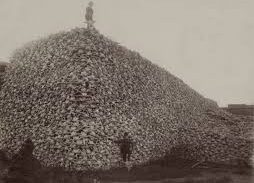

Some historians argue that because of low population numbers and the fact that some tribes engaged in herding large groups of buffalo off cliff tops and burning forest understory that it is not correct to label Natives as the first stewards of the land. This is, of course, incorrect. Many of these actions that these historians claim to be unsustainable, like the burning of forest understory, are actually now established conservation practices. Natives lived and interacted with the lands around them for thousands of years quite successfully until the infiltration and exploitation of white settlers. Also, when more sustainable options were available, or knowledge of thresholds were better understood, Natives changed practices to be more sustainable. For example, when horses were introduced to States, plains tribes adapted their hunting techniques and deviated from herding buffalo off cliffs. It wasn’t the Natives who decimated the buffalo, either. It was about the same time that Thoreau published Walden, that the US Government approved a policy to slaughter tens of millions of buffalo in order to starve and decimate the fierce plains tribes defending their lands and their livelihoods.

In terms of the American conservation effort, the Progressive era (1890s-1920s) represents the initial boom period of the movement. Even this era had divisive visions on what should be done with the rich and bountiful wilderness in America. Market forces, relentless logging, and unmitigated hunting raised concerns among leaders with two different viewpoints: conservation and preservation. Both movements were guided by contrasting viewpoints on how to manage American lands. The preservation movement, led by John Muir, sought to restrict and limit human use of and presence in wild areas and to protect and preserve landscapes. The conservation movement, led by President Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot sought to protect natural resources through sustainable resource extraction practices that still supported growth.

Before Roosevelt became president, he and John Muir worked together to increase awareness for stewardship needs throughout the nation. Preservation of iconic National parks like Yosemite and Sequoia occurred within one week of each other in 1890 through the passage of a congressional bill. When Roosevelt was sworn into office in 1901, conservation, not preservation, became a top national priority. During Roosevelt’s administration, though, more land was put under federal protection than all other presidents combined up to that point. In 1906, President Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act into law, which gave the president proclamation power to designate new national monuments and set aside land for protection. A burst of national parks, monuments, and forests were established under the Roosevelt administration. With the help of Gifford Pinchot, resource management practices garnered increased attention, although many differed from Native practices that had already proven successful.

From President Roosevelt to Papahānaumokuākea, Aldo Leopold to Al Gore, the rise of the environmental movement in the 1970s to pipelines, plastic pollution, and protests, the history of land stewardship in America has been a relentless tug-of-war between growth and sustainability, conservation and preservation, and conflicting visions. Perhaps no two administrations have exemplified this tug-of-war more so than the most recent. The Obama Administration protected almost twice as much area as President Roosevelt (albeit mostly oceanic land), while the Trump administration has reduced protected land areas, opening them to development, e.g., grazing and drilling. Fracking threatens to destroy aquifers, rivers, and lakes throughout the nation with large implications for environmental justice. Oil and gas lobbyists were recently recorded laughing at how President Trump is allowing them to destroy the environment for money. The flurry of environmental regulations put in place by the preservationist Obama administration are being rolled back at a frantic pace by the Trump administration. Indeed, these years may be the most important in American conservation history since the beginning of the movement in the Progressive era as climates continue to change, time continues to run out, and the tug-of-war continues on.