Southern Exposure: Climate Change and the Vulnerability of the South

In May, it will be a decade since I left my home state of North Carolina. I hadn’t planned to never go back, but circumstances and life decided to root me in the Pacific Northwest for the time being. I still journey back once or twice a year to see my family, but I never stay too long. Now, I have lived almost a third of my life in western Washington and currently call it home.

But the South is still dear to my heart. It’s hard to forget the earthly constellations of fireflies at night, soft sandy beaches, breezes through oak and hickory canopies, and the warmth of communities that are only matched by the area’s summer temperatures.

Still, I worry about my home state and the rest of the South. The South includes the states of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas. Like the rest of the nation and the world, it is facing the ever-increasing harsh impacts of climate change. But the South, for many reasons, precariously sits as the nation’s most vulnerable place to climate change.

What is the South vulnerable to?

Oxfam lists four main climate hazards that are having and will continue to have the greatest impact on the South: hurricane-force winds, flooding, sea level rise, and drought. If you think about the South and climate change impacts, you might imagine hurricanes. Hurricanes are large and can do incredible damage. While they are a normal part of the weather in the South, their intensity and frequency have been steadily increasing recently.

“That was the past though. As stronger winds topple trees and infrastructure, and heavier rains or rising oceans cause worse flooding, less and less of the impacted communities are spared leaving too many that need help and too few that can.”

During my childhood, I remember my parents and our neighbors meeting up after bad hurricanes to see who needed help and when. In the days to weeks without electricity following the storm, groups of neighbors would use the skills and tools they had to clear trees, fix roofs, deliver food, and search flooded areas. After one hurricane, my family coincidentally helped clear trees (twelve, I think) from the house my parents would eventually move our family to years later. That was the past, though. As stronger winds topple trees and infrastructure, and heavier rains or rising oceans cause worse flooding, less and less of the impacted communities are spared leaving too many that need help and too few that can.

If you were around in 2005, you most likely remember the destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and the Gulf Coast. Katrina and the failures to adequately help those impacted changed much in the South. For me, it showed that climate change is here and impacting us now. For those towns in the path of the storm, it laid bare their risks to hazards and their social vulnerabilities. For the rest of the South, the steady stream of refugees moving into their states and volunteer groups traveling out to help rebuild the Gulf Coast fed thoughts that this could happen to them, too.

Increasing storm strength and frequency will also increase the impacts of tornadoes, which are becoming more prevalent in the South. Heavy rainfall is becoming stronger and happening more often. I remember a few times in high school when it rained so hard that school was canceled because the bridges were flooded and unsafe to cross. Keep in mind that these were bridges that crossed creeks, not rivers, and this was not a hurricane. The combination of unusually heavy rain and aging infrastructure turned rainy days into days without school. While this was seen as great news to me as a high school student, school and bridge closures have huge impacts on working families.

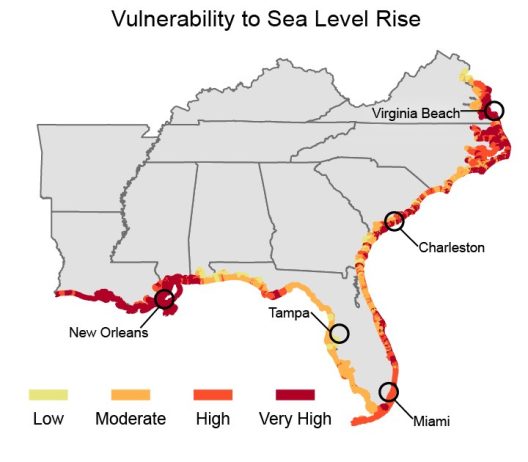

While sea level rise plus storm surges have devastating impacts on the South as ocean waters inundate whole communities during storms, sea level rise can regularly flood communities even on calm, sunny days as high tides reach higher and higher.

More droughts might seem contradictory to heavier rainfall, but increased average temperatures plus the lengthening time between rainfall events increases drought risk in the South. This impacts farmers, municipal water sources, private wells, and wildlife that depend on freshwater. According to Oxfam, more than 25% of the South now lies within a drought zone. During my childhood in NC, I witnessed several instances of forced water rationing and public prayers for rain from state leaders throughout the South.

Why is the South vulnerable?

The South is particularly vulnerable to stronger storms and sea level rise from climate change because much of it is a low-lying coastal plain. All this low-lying land is easily flooded with heavy rainfall, storm surge, and rising sea levels.

The South also has a high degree of social vulnerability on top of being vulnerable to climate hazards. The South is one of the most ethnically diverse parts of the nation as well as one of the poorest. Inequality is common and the history of slavery, racism, and their impacts felt today increase the vulnerability of Black and Brown communities in the South. These communities often have been pushed to live in geographically vulnerable areas. About an hour and a half drive from my childhood home lies the town of Princeville, NC. Princeville is the country’s oldest Black-founded town established right after the Civil War and Emancipation. Black residents gained title to some of the only unclaimed land left: the swampy lowlands next to the Tar River. The town has faced nine major flood events, and even though plans and funding for a protective levee were approved, they were discontinued when models showed that it would increase flooding in the larger, wealthier neighboring towns of Tarboro and Greenville. This is not unique to Princeville: Black, Brown, and impoverished communities are often situated in more vulnerable places with fewer resources to prepare for disasters. In the coming decades, flood risk in the US is projected to be highest in the South, and will disproportionately affect Black communities with a 40% flood risk increase in communities where one-fifth of the population is Black. This is particularly worrying since Black and Brown communities in the South have historically been underinvested. The increasing natural hazards, the legacy of poverty, and the geographic heritage of racism in the South combine to place this region in a precarious position in the face of climate change.

This is only a small part of the social vulnerability of the South. The pronounced social vulnerabilities of communities in the South are inextricably intertwined with race and the violent history of the South. While the communities in the South are vulnerable and have historically been the least funded from philanthropic and federal sources, they are also some of the most resilient communities and have not waited for permission to tackle what the future has in store for them.

The South’s past and present future

The South isn’t a static place. Maybe it moves as slowly as the muddy river waters that empty into the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, never quite forgetting how it’s gotten this far, but continues flowing forward. It is an ever-evolving place whose residents are preparing for the future while being impacted by climate change now. Opportunities and work are being done at every level from large federal investments to grassroots organizations lifting up their communities.

There is a lot of federal investment and planning for projects in the South that hope to reduce the region’s vulnerability. Recent federal legislation, namely the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure and Investment in Jobs Act, give hope through unprecedented levels of funding available for climate resiliency actions in the South. The money could be used to recover from disasters faced last year like Hurricane Idalia or historic flooding in Tennessee and Kentucky. While not perfect, the federal government’s preparation and disaster response is improving, using lessons learned from the failures of the post-Katrina recovery. The money is also needed for resiliency projects as southern states prepare for future disasters. In addition, more federal money will come in the form of 238 green energy projects planned throughout the South, bringing new job opportunities for large urban areas and small rural communities alike.

Resilience and planning work is also happening at the state level. Some states have developed action plans to increase community resilience. North Carolina and South Carolina both have enacted climate resiliency plans to study their own particular vulnerabilities and prepare ways to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

But the most hope that comes from the South is the current generation of grassroots organizations that carry on the long tradition of people power in the South. Groups like the Southeast Climate and Energy Network (SCEN) are working to create mutual aid networks, improve local infrastructure, and map community resources. Another group, the Mississippi People’s Movement (MPM), works to improve access to clean water and food systems, stop the local expansion of the fossil fuel industry, and create affordable housing in their area. In my home state of North Carolina, groups like the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (NCEJN) work to educate, organize, and connect resources to communities that are fighting environmental injustices, including those exacerbated by climate change.

“We are always better when working together and in my opinion, the people of the South truly shine when they work together.”

The impacts of climate change are already felt deeply in the South. Stronger storms, longer droughts, eroding coastlines, extreme heat, and other hazards are all putting pressure on the communities that live in this uniquely beautiful area. For many social and environmental reasons, this area that raised me is the most vulnerable and the least funded in the nation. The promise of more funding and planning for climate resiliency that is coming from the federal and some state governments is heartening. However, I am still wary of witnessing all the past mistakes and purposeful omissions in relief efforts. What gives me the most hope though, are the grassroots organizations like SCEN, MPM, NCEJN, and so many others that are rising to fill the unmet needs of these communities. We are always better when working together and in my opinion, the people of the South truly shine when they work together.