Community Engagement and Adaptation: NYC’s East Side Coastal Resiliency Project

On October 29, 2012, the tri-state area (New York, New Jersey, Connecticut) found itself in the middle of a perfect storm. Hurricane Sandy had claimed 50 lives in the Caribbean and wreaked havoc traveling up the eastern seaboard. An unusual shift in the position of the jet stream pulled the hurricane unexpectedly onto land exactly during the peak high tide and under a full moon, which caused tidal heights to be even greater than usual. As a result, Lower Manhattan was covered by 12 feet of water, 44 New Yorkers were killed, and almost $19 billion of infrastructure and property was destroyed.

Author Husiak, who grew up in the East Village and lived through Sandy, describes that fateful evening; “The night Sandy hit I was living with my parents. We were unsure of what was going to happen – we didn’t prepare any extra food or water. Around 8 p.m., I heard a huge explosion that echoed through my apartment complex. It sounded like a cannon had gone off. I watched out the window as the entire community lost power, and the blackout finally reached us. Later I learned that what I had heard was the explosion at the Con Eddison power plant caused by saltwater flooding. We didn’t get power back for days.” Hurricane Sandy revealed how vulnerable New York City communities and infrastructure are to flooding, which will only be exacerbated by climate change. Today, around 200,000 New Yorkers are directly threatened by flooding, and that number is expected to double by 2080. By mid-century, the damages from coastal storms are projected to exceed a billion dollars every year without serious intervention. Hurricane Sandy was a wake-up call for New York; we are dangerously unprepared for the impacts of climate change.

In the immediate aftermath of the storm, the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force was created. The destruction from Sandy simultaneously revealed the need for and offered an opportunity to build a coastline that will better protect against extreme storms while serving the needs of local residents. The Task Force initiated the Rebuild by Design competition to meet this need with the purpose of “[promoting] innovation by developing regionally-scalable but locally-contextual solutions that increase resilience in the region.” The innovative competition encouraged focusing design around community needs without worrying about constraints such as budget, political feasibility, or existing infrastructure. Design teams were flown into New Jersey and New York to observe damage, learn from affected residents, and better understand the areas they planned to improve. As described by Urban Institute:

First, community organizations provided background information on their

communities, sharing knowledge of their communities’ needs, the physical and

political landscapes of the region, and content knowledge in specific issue areas.

In the initial stages of the process, they shared knowledge through presentations

of their work to the design teams and then offered advice to the design teams as

they formed their ideas. Second, community organizations used their networks

and infrastructure to help design teams further engage the community by

directing them to other important organizations and leaders with whom they

could consult. Third, they helped organize and publicize community engagement

events through, e.g., hosting events, facilitating discussions, knocking on doors

and, in some cases, attending the RBD…presentations.

Insights from the collaborative process were used to create The Big U project. This was a ten-mile strip of usable greenspace around the southern point of Manhattan – hence the name “U” – that could safely flood and protect the city’s infrastructure during future storms. The design team continued to consult with dozens of local community organizations, convened town hall events and less formal gatherings to understand local residents’ needs and wants for the future of their neighborhoods. Some wanted wading pools on the East River, others wanted to turn the elevated FDR Drive highway into a tunnel and create a park on top. There was even talk about creating a climate-focused museum that could be protected by retractable floodgates. In the U.S., few climate adaptation projects have prioritized community input from inception, and even fewer have attempted this work at such a large scale. Unsurprisingly, this innovative process quickly faced serious barriers.

The Big U plan was too ambitious and too vague to become a reality; the plan was always intended to be scaled down. The first project to begin was the “East River Coastal Resiliency Project,” which would protect residents of the Lower East Side in Manhattan by adapting the East River Park and Stuyvesant Cove. The East River Park in particular is some of the only green spaces accessible to local residents; it has been an extremely significant area for community-building, education, and exercise, and allows people to build a relationship to the cultural and environmental history of the neighborhood. Historically populated by immigrant communities, the Lower East Side now consists of low-income public housing, extremely wealthy pockets of residents, and neighborhoods such as Chinatown, Little Ukraine, and Alphabet City all coexisting along the East River. While they all hope to benefit from the Rebuild by Design’s adaptation efforts, every individual who uses or values the riverside holds their own opinions about what that means.

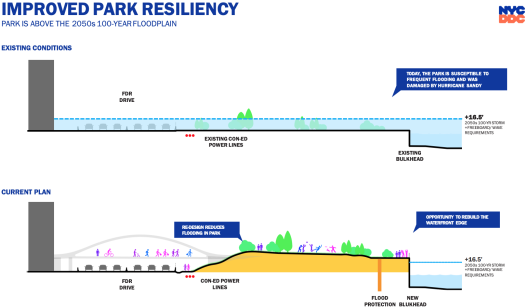

The East Side Coastal Resiliency Project, estimated to cost $760 million, was developed collaboratively with the deeply invested community over four years. The two-mile stretch of green space was going to be improved by adding a berm system at the southern end of the strip and deployable floodgates along the northern end of the park. One reason why it was designed to use berms was because the community wanted to conserve the existing park and mature trees, some of which are 100 years old. During future extreme storms, the berms would allow the park to flood and hold water back from the inner city.

But, in 2018 and seemingly overnight, city officials scrapped the co-generated adaptation plan for another. They offered no opportunity for input and quickly broke ground in 2020. The new East Side Coastal Resiliency Project, costing $1.45 billion, will see the beloved East Side River Park demolished and raised eight to nine feet and the Stuyvesant Cove Park replaced by floodwalls and floodgates. The raising of the East Side River Park was designed to protect the inner city from low probability predictions for extreme sea level rise in the 2050s. This project, which is underway and scheduled to be finished in 2026, became extremely divisive.

A quick Google search of “East River Coastal Resiliency Project” returns a slew of critiques as well as affirmations for the project, but almost all involved feel that the city’s decision to change the plan after years of community collaboration sowed distrust and resentment amongst residents against local government officials. Climate adaptation work is already incredibly controversial, and climate misinformation is rampant – the evasiveness of the New York City government has only compounded confusion and frustration amongst residents who are supposed to benefit from the flooding plans.

Those who support the plan cite the need for protection from future climate change impacts, and while they didn’t like how the city devised the latest project iteration, they affirm the need for action before another severe flooding event occurs. An environmental justice advocacy group for people of color, the Frontline Communities Coalition, wrote, “[the] E.S.C.R. is about saving lives and, in doing so, it will also save the homes and East River Park itself for future generations. For Black and Brown people living along the waterfront, prioritizing nonresilient park space over the at-risk families living and properties along the waterfront is nothing short of environmental racism.” The new East Side Coastal Resiliency project seems more protective than the old plan, and Frontline Communities Coalition’s statement highlights the vulnerability of at-risk residents and the subsequent need for immediate action.

On the other side, there has been much critical community feedback on the new East Side Coastal Resiliency project, a narrative primarily coming from environmentalists. One environmental group, “a thousand people a thousand trees,” stated on their Twitter page that “Killing 1,000 trees is not flood protection, it’s a real estate scam, a land grab of public space, on stolen land.” Another environmental group, East River Park Action, is strongly against the new plan – going so far as to sue the city – and hopes to return to the collaborative drawing board. They feel that the Environmental Impacts Statement does not address the environmental and ecological impacts of removing the 1,000 mature and historical trees (thus removing their extensive canopy), even though over 1,800 new salt-tolerant saplings will be planted to account for the ecological destruction.

Obviously, there is a huge variety of conflicting opinions on the project, even as it inexorably moves forward. It is difficult to make generalizations about which groups of people feel which ways; political pressure should not be discounted as a driving force behind the strength and perspective of certain narratives and is very hard to unearth. Nevertheless, there are a few big questions and takeaways that have risen from this conflict:

Whose needs should be prioritized in adaptation planning, and is there a way to accommodate all stakeholders in decision-making? How might adaptation processes balance the need for preserving past and present-day value while meeting the needs of our future climate and social systems? How can governments work to ensure trust and communication when employing collaborative planning?

To address this final question, the city government has acknowledged their misstep. The deputy commissioner of the city’s Department of Design and Construction stated in a New York Times interview that “‘we were facing a deadline to spend the federal funds and wanted to get the project built as quickly as possible to get the flood protection in place,’ he added. ‘We really didn’t consider the new design to be a radical change from the original one.’” Given that one of the central tenets for the project design was community collaboration, this seems like an obvious oversight. The city is now attempting to better communicate while still advancing the project. Specifically, they are rebuilding trust by increasing transparency and considering the environmental quality concerns of the community. The team “provides regular construction updates at various community events and meetings, including local community boards and meetings of the ESCR Community Advisory Group.” They are also working to provide air quality monitoring of the park construction sites for the public.

While the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project is already significantly underway, future adaptation projects can hopefully avoid its mistakes. It is evident that the radical and uncommunicated change from the city was a serious slight against the community, especially because the community has historically been politically invalidated. Not only did the shift to the new plan create confusion, but it sowed a deep sense of distrust that will take time and effort to repair. If more politically or operationally focused stakeholders had been invited into earlier stages of the process, perhaps the old plan could have avoided the issues that caused the quick reversal. Even if the project needed to evolve, a clear and engaging communication process could have at least preserved trust in the city and other project leaders. If adaptation projects are meant to protect the residents of a place, is community trust not a critical measure of its success?